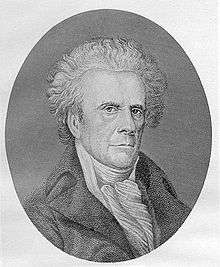

Johann Schweighäuser

Johann Schweighäuser (German: [ˈʃvaɪkˌhɔɪzɐ]; French: Jean Geoffroy Schweighaeuser; June 25, 1742 – January 19, 1830), was a French classical scholar.

Biography

He was born at Strasbourg, the son of a pastor of the church of Saint Thomas. From an early age his favourite subjects were philosophy (especially Scottish moral philosophy as represented by John Hutchinson and Adam Ferguson) and Oriental languages; Greek and Latin he took up later, and although he owes his reputation to his editions of Greek authors, he was always diffident as to his classical attainments. After visiting Paris, London and the principal cities of Germany, he became assistant professor of philosophy (1770) at University of Strasbourg.[1]

When the French Revolution broke out, he was banished; in 1794 he returned, and after the reorganization of the Academy in 1809 was appointed professor of Greek. He resigned his post in 1824, making way for his son.[1] In 1826 he was decorated by the Royal Society of London.

Works

Schweighäuser's first important work was his edition of Appian (1785), with Latin translation and commentary, and an account of the MSS. On Brunck's recommendation, he had collated an Augsburg MS. of Appian for Samuel Musgrave, who was preparing an edition of that author, and after Musgrave's death he felt it a duty to complete it. His Polybius, with translation, notes and special lexicon, appeared between 1789 and 1795. But his chief work is his edition of Athenaeus (1801–1807), in fourteen volumes, one of the Bipont editions.[1] According to Paul Louis Courier, this edition is a great progress on the one of Isaac Casaubon, which was two centuries old at the time.[2] His Herodotus (1816; lexicon, 1824) is less successful; he depends too much on earlier editions and inferior MSS., and lacks the finer scholarship necessary in dealing with such an author. Mention may also be made of his Enchiridion of Epictetus and Tabula of Cebes (1798), which appeared at the time when the doctrines of the Stoics were fashionable; the letters of Seneca to Lucilius (1809); corrections and notes to Suidas (1789); and some moral philosophy essays. His minor works are collected in his Opuscula academica (1806).[1]

Family

His son, Johann Gottfried, was also a distinguished scholar and archaeologist.[1]

Bibliography

See monographs by J. G. Dahler, C. L. Cuvier, F. J. Stiévenart (all 1830), L. Spach (1868), Ch. Rabany (1884), the two last containing an account of both father and son.[1]

References

- Chisholm 1911, p. 392.

- Courier 1964, p. .

Sources

- Courier, P. L. (1964). Oeuvres complètes. Paris: Pleiade.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)