Jay DeFeo

Jay DeFeo (March 31, 1929 – November 11, 1989) was a visual artist who first became celebrated in the 1950s as part of the spirited community of Beat artists, musicians, and poets in San Francisco. Best known for her monumental work The Rose, DeFeo produced courageously experimental works throughout her career, exhibiting what art critic Kenneth Baker called “fearlessness.”[1]

Jay DeFeo | |

|---|---|

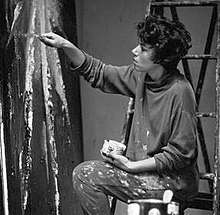

DeFeo working on The Jewel | |

| Born | Mary Joan DeFeo March 31, 1929 |

| Died | November 11, 1989 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | The Rose |

Life and Work

Early Life

Jay DeFeo was born Mary Joan DeFeo on March 31, 1929, in Hanover, New Hampshire, to a nurse from an Austrian immigrant family and an Italian-American medical student.[2]

In 1932, the family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where her father graduated from Stanford University School of Medicine and became a traveling doctor for the Civilian Conservation Corps. Between 1935 and 1938, DeFeo traveled around rural parts of Northern California with her parents, and also spent extensive time with her maternal grandparents on a farm in Colorado as well as with her paternal grandparents in the more urban Oakland, California. When DeFeo’s parents divorced in 1939, DeFeo joined her mother in San Jose, California, where DeFeo attended Alum Rock Union School and excelled in art.[3]

In high school DeFeo acquired the nickname “Jay,” which she used as her common name for the rest of her life. An important early mentor was her high school art teacher, Lena Emery, who took her to museums to see works by Picasso and Matisse, opening up a new world to the young artist.[4] DeFeo enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley, in 1946, studying with many well-known art professors, including Margaret Peterson O’Hagan. Fellow students included Pat Adams, Sam Francis, and Fred Martin.[5][6]

In her artwork, she resisted what she called "the hierarchy of material", using plaster and mixing media to experiment with effects, a thread one can see running through the art of that time, especially on the West Coast.

Beginning Art Career

In 1953 DeFeo returned to Berkeley, where she created large plaster sculptures, works on paper, and small wire jewelry. She met the artist Wally Hedrick and they married in 1954. At first they lived on Bay Street in San Francisco, close to the California School of Fine Arts, where DeFeo worked as an artist’s model.[7] DeFeo focused on making jewelry to support herself, as well as creating small paintings and drawings. It was during this time that DeFeo had her first one-person exhibition at The Place, a San Francisco tavern and poets’ hangout. DeFeo also exhibited her jewelry at Dover Galleries in Berkeley, and was included in many group exhibitions over the next few years.[8]

Early in 1955, DeFeo was featured— along with Julius Wasserstein, Roy De Forest, Sonia Gechtoff, Hassel Smith, Paul Sarkisian, Craig Kauffman, and Gilbert Henderson—in a group exhibition, Action, independently curated by Walter Hopps in Santa Monica, where the paintings featured were installed around the base of a working merry-go-round.[9] Later that year, DeFeo and Hedrick moved to 2322 Fillmore Street, into a spacious second-floor flat, where DeFeo was able to work on a larger scale. The Fillmore Street building—whose inhabitants at various times included the visual artists Sonia Gechtoff, Jim Kelly, Joan Brown, Craig Kauffman, John Duff, and Ed Moses; the poets Joanna and Michael McClure; and the musician Dave Getz—became a hangout for other artists, writers, and jazz musicians.[10] The artist Billy Al Bengston remembers DeFeo as having “style, moxie, natural beauty and more ‘balls’ than anyone.”[2]

Hedrick, Deborah Remington, Hayward King, David Simpson, John Allen Ryan, and Jack Spicer founded The 6 Gallery at 3119 Fillmore Street, at the location of the King Ubu Gallery, which had been run by Jess and Robert Duncan.[11] Joan Brown, Manuel Neri, and Bruce Conner would become associates of The 6 Gallery. DeFeo was present when Allen Ginsberg first read his poem Howl at the famous The 6 Gallery reading in 1955.[12] In 1959, DeFeo became an original member of Bruce Conner’s Rat Bastard Protective Association.[13]

In 1959, DeFeo was included in Dorothy Canning Miller’s seminal exhibition Sixteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, alongside Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, and Louise Nevelson, among others.[14][15] Following this she had a solo exhibition in Los Angeles at the Ferus Gallery, started by Walter Hopps and Ed Kienholz.[16]

The Rose

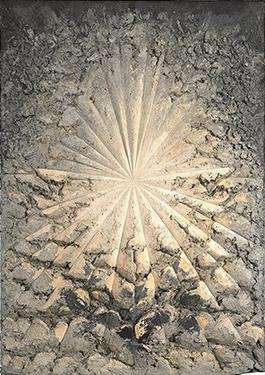

DeFeo’s best-known painting, The Rose (1958–66) preoccupied her for almost eight years. Selected by Thomas Hoving for his book Greatest Works of Art of Western Civilization, this masterwork stands over ten and a half feet high and weighs more than one ton.[17][18][19] As she worked on it, DeFeo built up and then carved away at the paint, in an almost sculptural process. In the end a starburst motif emerged with ridges of white paint radiating out to rougher textured gray material sparkling with mica.

The greater part of DeFeo’s work on The Rose terminated when she was evicted from her Fillmore Street apartment in November 1965.[20] Her friend Bruce Conner stated that an “uncontrolled event” was necessary to force her to finish this work, and he documented its removal from her apartment in a short film titled The White Rose (1967).[21] As the film shows, the painting was so large that the wall below a window opening had to be knocked out to remove it. Conner captured DeFeo dangling her feet from a fire escape as she watched the work being removed by forklift and then carried off in a moving van.[22] The painting was transported to the Pasadena Art Museum, where DeFeo added finishing details in 1966, before taking a four-year break from creating art.[23] [24] In 1969, the work was finally shown in solo exhibitions at the Pasadena Art Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA), with an accompanying essay authored by Fred Martin.[25] Martin later arranged for the painting to be stored at the San Francisco Art Institute, where it remained hidden behind a wall, in need of conservation, until 1995, when the Whitney Museum of American Art conserved and acquired the work for its collection.[26]

Artistic Style and Later Career

During her four decades of making art, DeFeo worked in a variety of media, creating drawings, paintings, sculpture, jewelry, photographs, photocopies, collages, and photo collages. Using an experimental approach to each medium, DeFeo developed her own “visual vocabulary,” playing with scale, color vs. black and white, texture or the illusion of texture, and precision vs. ambiguity. She wrote, “I do believe that more so than most artists, I maintain a kind of consciousness of everything I’ve ever done while I’m engaged on a current work.”[27] DeFeo often made her artwork in series—exploring, for example, light and dark versions, as well as mirror opposites. At times her artwork took off from a small quotidian object, such as a dental bridge or swimming goggles, transforming the everyday into something with “universal character.”[28]

During the 1970s, DeFeo took a particular interest in photography.[29] In 1970, a friend loaned DeFeo a Mamiya camera, and with the help of photography students in her art classes, she learned how to develop film and make prints. When DeFeo won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1973, she bought a Hasselblad camera and built a darkroom in her home, continuing to explore photography and photo collage for several years.[30] Untitled, from 1973, is an example of a DeFeo photo collage in which she combines images of recognizable objects in surprising juxtapositions.[31] In the late 1970s, DeFeo’s photography focused more on her work in progress in the studio, which evolved into a “visual diary” made of hundreds of contact sheets.[32]

During the 1980s DeFeo returned to oil paint, after working primarily in acrylic for a decade. In the summer of 1984, she traveled to Japan with her friend and fellow Mills College professor Mary-Ann Milford. This trip, along with an exhibit of Japanese helmets, inspired her 1987 Samurai drawing series.[33] In the summer of 1987, DeFeo traveled to Africa, inspiring her to produce a series of abstract drawings called Reflections of Africa, using a generic tissue box as her concrete starting-off point.[34] In Africa, DeFeo made it to the summit of Mt. Kenya (more than 17,000 feet), realizing a long-held dream of climbing a major mountain.[35]

For years DeFeo taught art part-time at various Bay Area institutions, including the San Francisco Art Institute (1964–71), the San Francisco Museum of Art (1972–77), Sonoma State University (1976–79), the California College of Arts and Crafts (1978–81), and UC Berkeley (1980). She received her first full-time position at Mills College (1980–89), where she eventually became the Lucie Stern Trustee Professor of Art.[36]

Personal Life

With the eviction from Fillmore Street, Hedrick and DeFeo separated and divorced in 1969. In 1967, she began a thirteen-year relationship with John Bogdanoff, a younger man, and they eventually settled in Larkspur in Marin County.[37][38] Separated from Bogdanoff and teaching at Mills College, she moved to Oakland in 1981 and built out a large a live/work studio where she continued to expand on her ideas through painting, drawing, photocopy, and collage.[39] Her life was filled with many good friends, inspiring students, and friendly dogs. She was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1988 but continued to work prolifically.[40][41] She died on November 11, 1989, at the age of 60.[42]

Exhibitions and Collections

The Whitney Museum of American Art, which holds the largest public collection of DeFeo’s work, presented a major retrospective from February 28 to June 2, 2013—also shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.[43] Subsequent solo exhibitions of DeFeo’s work have been held at the San José Museum of Art (2019)[44]; Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York (2014 and 2018)[45]; Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Beverly Hills, CA (2016 and 2018)[46]; Galerie Frank Elbaz, in Dallas (2018) and Paris (2016)[47], Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich (2013) [48], and Peder Lund, Oslo (2015) [49], among others.

In the years since the seminal Sixteen Americans show, DeFeo’s work has been included in numerous group exhibitions, most recently at The Menil Collection, Houston (2020), Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA (2020), San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose (2020), Museum of Modern Art, New York (2019), The Anderson Collection at Stanford University (2019), The Getty Center, Los Angeles (2019), Tate Modern, London (2018), Secession, Vienna (2018), Victoria Miro Mayfair, London (2018), Le Consortium, Dijon (2018), Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, CO (2018), Musée National Picasso-Paris (2018), Mills College Art Museum, Oakland, CA (2018), Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco (2018), CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco (2018), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2017), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2017), Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (2017), Centre Pompidou, Paris (2016), and Denver Art Museum (2016).

In addition to the Whitney Museum of American Art, DeFeo’s work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum, Centre Pompidou, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Menil Collection, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Norton Simon Museum, the Berkeley Art Museum at the University of California, Berkeley, the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art, and the Mills College Art Museum.

Legacy

The Jay DeFeo Foundation, a private foundation, was established under the terms of DeFeo’s will to encourage the arts, preserve her works, and further their public exposure. More information on Jay DeFeo and The Jay DeFeo Foundation can be found at www.jaydefeofoundation.org.

Notes

- "'Jay DeFeo' review: Fearless art". Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Schjeldahl, Peter (2013-03-18). "Flower Power". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Tooker, Dan. "Dan Tooker Interviews Fred Martin". Art International, Volume XIX/9, November 20, 1975.

- DeFeo, Jay. Lecture at San Francisco Art Institute, 11 Feb. 1980. Audio recording. Archives of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Deborah, Treisman (June 6, 2017). The Dream Colony (epub ed.). Bloomsbury USA. p. 50. ISBN 978-1632865298

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Cotter, Holland. " 'Jay DeFeo - A Retrospective' at The Whitney" The New York Times, Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Its members included Jay DeFeo, Michael McClure, Manuel Neri and Joan Brown. See Rebecca Solnit, "Heretical Constellations: Notes on California, 1946–61", in Sussman (ed.), Beat Culture and the New America, 69–122, especially p. 71.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Phaidon Editors (2019). Great Women Artists. Phaidon Press. p. 116. ISBN 0714878774.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Green, Jane, and Levy, Leah, eds. Jay DeFeo and “The Rose.” Berkeley and New York: University of California Press and Whitney Museum of American Art, 2003.

- "Jay DeFeo: The Rose 1958 - 1966". whitney.org. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- Farago, Jason. "Jay DeFeo" Archived April 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Frieze, Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Traps, Yevgeniya. "Romance of the Rose: On Jay DeFeo" The Paris Review, Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Deborah, Treisman (June 6, 2017). The Dream Colony (epub ed.). Bloomsbury USA. p. 50. ISBN 978-1632865298

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- "Jay DeFeo: About this artist", The Whitney Museum of American Art. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Martin, Fred. "Jay DeFeo: The Rose" Pasadena Art Museum, 1969.

- Green, Jane, and Levy, Leah, eds. Jay DeFeo and “The Rose.” Berkeley and New York: University of California Press and Whitney Museum of American Art, 2003.

- DeFeo, Jay. "My Visual Vocabulary" in Jay DeFeo: The Ripple Effect, 139-146

- DeFeo, Jay. Oral history interview by Paul Karlstrom, 1975 June 3–1976 January 23. Archives of American Art. [Link to: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-jay-defeo-13246].

- Keller, Corey. “My Favorite Things: The Photographs of Jay DeFeo.” In Miller, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 73–79

- "The Jay DeFeo Foundation - "Behold! The Tripod" by Elisabeth Sussman". www.jaydefeo.org.

- Honolulu Museum of Art, wall label, Untitled by Jay DeFeo, 1973, accession TCM.1998.5.1.jpg

- Keller, Corey. “My Favorite Things: The Photographs of Jay DeFeo.” In Miller, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 73–79.

- Miller, Dana. “Jay DeFeo: A Slow Curve.” In Miller, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 15–53.

- Miller, Dana. “Jay DeFeo: A Slow Curve.” In Miller, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 15–53.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Wally Hedrick, Goldberg, Lee, di Rosa Artist Interview Series: Wally Hedrick, 2009, p. 18.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- Schjeldahl, Peter (2013-03-18). “Flower Power”. The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- Cotter, Holland. " 'Jay DeFeo - A Retrospective' at The Whitney" The New York Times, Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Kamin, Diana, and Van Dyke, Meredith George. “Chronology”. In Miller, Dana, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, 281–95. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013.

- "Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective". Whitney Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Undersoul: Jay DeFeo". San Jose Museum of Art. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Jay DeFeo". Mitchell-Innes & Nash. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Jay DeFeo". Marc Selwyn Fine Art.

- "Jay DeFeo - galerie frank elbaz". www.galeriefrankelbaz.com.

- https://www.presenhuber.com/home/artists/DEFEO-JAY/Works.html/

- "Jay DeFeo".

External links

- The Jay DeFeo Foundation

- Smithsonian Archives, Interview with DeFeo, 1975: Transcript, Audio excerpt

- New Yorker magazine, "The Art World" article called "Flower Power".