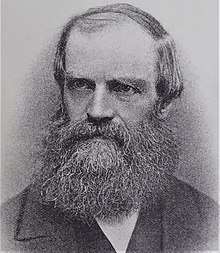

James Wilson (Archdeacon of Manchester)

James Maurice Wilson (6 November 1836, Castletown, Isle of Man – 15 April 1931, Steep, Petersfield, Hampshire, England) was a British priest in the Church of England as well as a theologian, teacher and astronomer.

Early life

Wilson and his twin brother, Edward Pears Wilson, attended King William's College on the Isle of Man from August 1848 to midsummer 1853 (his twin died in December 1856). Their father Edward, vicar of Nocton in Lincolnshire, had earlier been headmaster there. According to his autobiography, Wilson had a rather unhappy time at King William's College. He later studied at Sedbergh School.

Wilson entered St John's College, Cambridge, in 1855, where he was Senior Wrangler in 1859.[1] He received a Master of Arts degree in 1862 and was a fellow from 1859 to 1868.

Career

Wilson was a major figure in the development and reform of Victorian public schools and promoted the teaching of science, which had until then been neglected. He was maths and science master at Rugby School from 1859 to 1879 and headmaster of Clifton College from 1879 to 1890.

He made astronomical observations (particularly of double stars) at Temple Observatory at Rugby with his former student George Mitchell Seabroke. Temple Observatory was named after Frederick Temple, headmaster of Rugby School, who later became Bishop of Exeter and Archbishop of Canterbury.

Wilson was encouraged by Temple to write the textbook Elementary Geometry, which was published in 1868. Until that time, Euclid's Elements had remained the standard textbook used in British schools.

With Joseph Gledhill and Edward Crossley, Wilson co-wrote Handbook of Double Stars in 1879, which became a standard reference work in astronomy. His astronomical observations seem to have come to an end after he left Rugby and went to Clifton.

While at Clifton, he successfully pushed for the creation of St Agnes Park in Bristol, as part of a plan to improve the lives of the urban poor.

After his teaching career, he became Vicar of Rochdale, Archdeacon of Manchester from 1890 to 1905, a canon of Worcester Cathedral from 1905 to 1926 and vice-dean of the cathedral. He was Hulsean lecturer at Cambridge in 1898; Lady Margaret Preacher at Cambridge in 1900; and Lecturer in Pastoral Theology at Cambridge in 1902.

He wholeheartedly accepted the theory of evolution and its implications for the literal interpretation of the Bible. He gave two lectures in 1892 in which he accepted Darwinism and argued that it was compatible with a higher view of Christianity; the lectures were published by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, which had a few years earlier strongly opposed Darwinian ideas.

In 1921, he served for one year as president of The Mathematical Association of the UK.

In 1925 he wrote an essay entitled "The Religious Effect of the Idea of Evolution". He wrote a number of books, including Life after Death "with replies by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle" in 1920. In addition to spiritual works, he co-wrote an astronomy book on double stars (mentioned above) and mathematical books on geometry and conic sections. He contributed the article "On two fragments of geometrical treatises found in Worcester Cathedral" to the Mathematical Gazette (March 1911, p. 19).

Family

In 1868 he married his first wife, Annie Elizabeth Moore. Their first child was the leading civil servant Mona Wilson.[2] His first wife died after giving birth to their fourth child in 1878. She was a cousin once removed of Arthur William Moore, a proponent of the Manx language.

In 1883 he married his second wife, Georgina Mary Talbot. Their sons included Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson, who became a British colonial administrator in Baghdad and was killed in action in World War II; 2nd Lt. Hugh Stanley Wilson (1885–1915), who died in World War I and is buried in the military cemetery at Hébuterne, Pas de Calais; and the tenor Sir Steuart Wilson. From his notes, Arnold and Steuart published the posthumous James M. Wilson: An Autobiography (London, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1932)

References

- "Wilson, James Maurice (WL855JM)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Mona Wilson. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70137.

- Clifton College Register

External links

- Works by James Maurice Wilson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Wilson at Internet Archive

- Neale, Charles Montague (1907). The senior wranglers of the University of Cambridge, from 1748 to 1907. With biographical, & c., notes. Bury St. Edmunds: Groom and Son. p. 41. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "extract from James M. Wilson: An Autobiography 1836–1931". isle-of-man.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "A distinguished early group". isle-of-man.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2004. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- One-paragraph biography

- "King William's College Register: entrances in August 1848". Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Wilson, James Maurice (1836–1931) Schoolmaster Scientist Antiquary Canon of Worcester". National Register of Archives. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- Mention of an obituary in 1932 QJ 88 (Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of the UK), not online

- Marriott, R. A. (1991). "The 81⁄4-inch refractor of the Temple Observatory, Rugby". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 101 (6): 343–350. Bibcode:1991JBAA..101..343M. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "The Mathematical Gazette Index for 1909 to 1919". Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- White, Andrew Dickson. A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. p. 106. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

In two very remarkable lectures given in 1892 at the parish church of Rochdale, Wilson, Archdeacon of Manchester, not only accepted Darwinism as true, but wrought it with great argumentative power into a higher view of Christianity; and what is of great significance, these sermons were published by the same Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge which only a few years before had published the most bitter attacks against the Darwinian theory.

- V, W. W. (30 May 1931). "Obituary:The Ven. Dr. J. M. Wilson". Nature. 127 (3213): 824–825. Bibcode:1931Natur.127..824W. doi:10.1038/127824a0.

- Wilson, J. M. (1868). Elementary Geometry. London: Macmillan & Co. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "James Maurice Wilson". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- William Brock (8 September 1977). "Founding fathers of science education (5): Formalising science in the school curriculum". New Scientist. 75 (1068): 604–605. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Percival |

Headmaster of Clifton College 1879–1890 |

Succeeded by Michael George Glazebrook |