James Hackman

James Hackman (baptized 13 December 1752, hanged 19 April 1779), briefly Rector of Wiveton in Norfolk, was the man who murdered Martha Ray, singer and mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich.[1]

Early life

Baptized on 13 December 1752 at Gosport, Hampshire, Hackman was the son of William and Mary Hackman. His father had served in the Royal Navy as a lieutenant. Hackman was apprenticed to a mercer, and although according to some accounts he became a member of St John's College, Cambridge, no record of this can be traced at Cambridge.[1]

Career

In 1772, Hackman was purchased a commission as an ensign in the 68th Regiment of Foot,[2] and in 1776 was promoted lieutenant,[3] but by early 1777 he had resigned from the army[4] to become a clergyman. On 24 February 1779, Hackman was ordained a deacon of the Church of England and on 28 February a priest, and on 1 March 1779 was instituted as Rector of Wiveton, a place that he may never have visited.[1][5]

Martha Ray

In about 1775, while he was a serving army officer, Hackman visited Lord Sandwich's house at Hinchingbrooke and met his host's mistress Martha Ray.[1] She was "a lady of an elegant person, great sweetness of manners, and of a remarkable judgement and execution in vocal and instrumental music"[6] who had lived with Lord Sandwich as his wife since the age of seventeen and had given birth to nine of his children.[1] Sandwich also had a wife, from whom he was separated, who was considered mad and who lived in an apartment at Windsor Castle.[5] This was the same Lord Sandwich who is said to have called for a piece of beef between two pieces of bread, thus originating the word sandwich. He was a patron of the explorer Captain James Cook, who named the Sandwich Islands after him.[5]

Hackman struck up a friendship with Martha Ray (who was several years older than he was)[1] and was later reported to have become besotted with her.[5] They may have become lovers and discussed marriage, but this is disputed.[1] Although rich, Sandwich was usually in debt and offered Martha Ray no financial security.[5] However, whatever was between Hackman and Martha Ray ended when he was posted to Ireland.[1]

On 7 April 1779, a few weeks after his ordination as a priest of the Church of England, Hackman followed Martha Ray to Covent Garden,[7] where she had gone to watch a performance of Isaac Bickerstaffe's comic opera Love in a Village with her friend and fellow singer Caterina Galli.[1] Suspecting that Ray had a new lover, when Hackman saw her in the theatre with William Hanger, 3rd Baron Coleraine, he left, fetched two pistols, and waited in a nearby coffee house. After Ray and Galli came out of the theatre, Hackman approached the ladies just as they were about to get into their carriage. He put one pistol to Ray's forehead and shot her dead. With the other he then tried to kill himself but made only a flesh wound. He then beat himself with both discharged pistols until he was arrested and taken, with Martha Ray's body, into a tavern in St James's Street. Two letters were found on Hackman, one addressed to his brother-in-law, Frederick Booth, and a love letter to Martha Ray: both later appeared in evidence at the murder trial.[1]

When Lord Sandwich heard what had happened, he "wept exceedingly".[8]

On 14 April 1779, Martha Ray was entombed inside the parish church of Elstree, Hertfordshire, but her body was later moved into the cemetery.[1] On the instructions of Lord Sandwich, she was buried in the clothes she had been wearing when killed.[5]

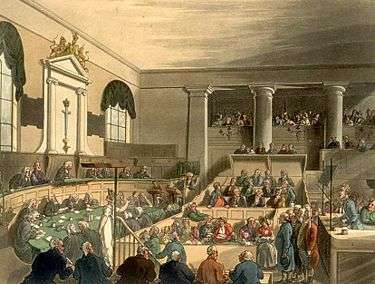

Trial

Hackman was quickly committed to the Tothill Fields Bridewell.[9] As "James Hackman, Clerk", he was indicted for "the wilful murther of Martha Ray, spinster" on the inquisition of the coroner.[10]

On 16 April 1779, just nine days after the event, Hackman was tried for murder at the Old Bailey. Despite having previously decided to plead guilty, in the event he pleaded not guilty, explaining that "the justice of my country ought to be satisfied by suffering my offence to be proved".[9][10]

John McNamara, Esq., gave evidence that on the evening of 7 April, he believed at some time after eleven o'clock, he came out of the playhouse with Martha Ray, and having seen her "in some difficulties at the playhouse", offered his help in handing her to her carriage. She took his arm. As they came out of the passage into the Covent Garden playhouse and were two steps from the carriage, he heard the report of a pistol, while Miss Ray was still holding his right arm with her left hand. She fell instantly. He thought the pistol had been "fired out of wantonness" and that Miss Ray had fainted. He knelt to help her, but found blood on his hands, and got her into the Shakspeare tavern. He did not see Hackman at the time, but after he had been arrested, asked him what had possessed him, and he answered "that it was not a proper place to ask that question, or something to that effect... I asked him his name, and I understood from him that his name was Hackman; I think he pronounced his name with an H. I asked him if he knew anybody. He said, he knew a Mr. Booth, in Craven-street in the Strand, and desired he might be sent for. He desired to see the lady. I did not tell him she was dead; somebody else did. I objected to his seeing her at that time. I had her removed into another room. From the great quantity of blood I had about me I got sick, and was obliged to go home. I know no more about it."[10]

Mary Anderson, a fruit seller, gave evidence that she was standing close by the carriage. She is recorded as saying:[10]

I was standing at the post. Just as the play broke up I saw two ladies and a gentleman coming out of the playhouse; a gentleman in black followed them. Lady Sandwich's coach was called. When the carriage came up, the gentleman handed the other lady into the carriage; the lady that was shot stood behind. Before the gentleman could come back to hand her into the carriage the gentleman in black came up, laid hold of her by the gown, and pulled out of his pocket two pistols; he shot the right hand pistol at her, and the other at himself. She fell with her hand so [describing it as being on her forehead] and died before she could be got to the first lamp; I believe she died immediately, for her head hung directly. At first I was frightened at the report of the pistol, and ran away. He fired another pistol, and dropped immediately. They fell feet to feet. He beat himself violently over the head with his pistols, and desired somebody would kill him.

Anderson said she had identified Hackman in Tothill Fields Bridewell the next day and she did so again in court, pointing to the prisoner.[10]

Richard Blandy, a constable, gave evidence that he had been coming from Drury-Lane house and that as he came by the piazzas in Covent Garden he heard two pistol shots and then heard somebody say two people were killed. Approaching, he saw the surgeon had Hackman and a pistol in his hand. A Mr Mahon had given Blandy the pistol and asked him to take care of the prisoner and to take him to Mahon's house. The prisoner was bloody, wounded in the head, and very faint. When Blandy came to the corner by the Red Lion, the door was shut, and he was then asked to take the prisoner back to the Shakspeare tavern, where Mr Mahon was. Blandy searched the prisoner's pocket and found two letters, which he gave to Mr Campbell, master of the Shakspeare tavern. He could say nothing else about the letters.[10]

James Mahon, an apothecary, gave evidence that he lived at the corner of Bow Street. Coming through the piazzas in Covent-Garden, he heard two pistols go off. Going back, he saw a gentleman lying on the ground, with a pistol in his left hand, beating himself violently and bleeding copiously. The prisoner was the gentleman. Mahon had taken the pistol away from him and given it to the constable, asking him to take the prisoner to his house for the wound to be dressed. He had seen nothing of the lady until two or three minutes later he saw her lying at the bar, with a mortal wound, and said he could not help her.[10]

Dennis O'Bryan, a surgeon, gave evidence that he had examined Miss Ray's body at the Shakspeare tavern on the night of the murder. He found the wound to be mortal, could find no sign of life, and pronounced the woman dead. The wound was in the 'centra coronalis' (the crown of the head) and the ball had come out under the left ear.[10]

Hackman gave evidence for himself, reading a prepared statement to the court, which was probably written by the lawyer and writer James Boswell, who although not professionally engaged was closely associated with the defence.[11] The statement afterwards appeared in all the newspapers. Hackman admitted that he had killed Ray, but he claimed he had only meant to kill himself. He said:[10][12]

I stand here this day the most wretched of human beings, and confess myself criminal in a high degree; yet while I acknowledge with shame and repentance, that my determination against my own life was formal and complete, I protest, with that regard to truth which becomes my situation, that the will to destroy her who was ever dearer to me than life, was never mine till a momentary phrensy overcame me, and induced me to commit the deed I now deplore. The letter, which I meant for my brother-in-law after my decease, will have its due weight as to this point with good men. Before this dreadful act, I trust nothing will be found in the tenor of my life which the common charity of mankind will not excuse. I have no wish to avoid the punishment which the laws of my country appoint for my crime; but being already too unhappy to feel a punishment in death, or a satisfaction in life, I submit myself with penitence and patience to the disposal and judgement of Almighty God, and to the consequences of this enquiry into my conduct and intention.

Hackman's defence counsel submitted to the court that Hackman was insane and that the killing of Martha Ray was unpremeditated, as shown by the letter to her found on him.[1]

William Halliburton was sworn and produced the other letter found in the prisoner's pocket, which he said he had had from Booth. Mahon identified it as a letter taken from the prisoner, which he said Booth had opened and read in his presence. The letter, addressed to "Frederick Booth, Esq. Craven street, in the Strand", was read into the record:[10]

My dear Frederick, When this reaches you I shall be no more, but do not let my unhappy fate distress you too much; I have strove against it as long as possible, but it now overpowers me. You well know where my affections were placed; my having by some means or other lost her's [sic] (an idea which I could not support) has driven me to madness. The world will condemn me, but your good heart will pity me. God bless you my dear Fred. Would I had a sum to leave you, to convince you of my great regard: you was my only friend. I have hid one circumstance from you, which gives me great pain. I owe Mr. Knight, of Gosport, 100 ℓ. for which he has the writings of my houses; but I hope in God, when they are sold, and all other matters collected, there will be nearly enough to settle our account. May Almighty God bless you and yours with comfort and happiness; and may you ever be a stranger to the pangs I now feel. May heaven protect my beloved woman, and forgive this act, which alone could relieve me from a world of misery I have long endured. Oh! if it should ever be in your power to do her any act of friendship, remember your faithful friend, J. Hackman.

Mr Justice Blackstone, presiding at the trial, summed up the case against Hackman. He told the jury that the crime of murder did not demand "a long form of deliberation" and that Hackman's letter to Frederick Booth showed "a coolness and deliberation which no ways accorded with the ideas of insanity".[13] Hackman was convicted and sentenced to be hanged.[1]

In a newspaper report of the trial, Hackman was described as five feet nine inches tall, "very genteely made, and of a most polite Address".[14]

After the trial, James Boswell told Frederick Booth that Hackman had behaved "with Decency, Propriety, and in such a Manner as to interest everyone present".[1][15]

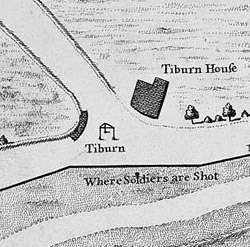

Execution

Hackman was hanged at Tyburn on 19 April 1779. He travelled there in a mourning coach, accompanied by the sheriff's officer and two fellow clergymen, the Rev. Moses Porter, a curate friend from Clapham, and the Rev. John Villette, the chaplain of Newgate Prison.[1] James Boswell later denied rumours that he had also been in the coach.[16]

At Tyburn, "Hackman... behaved with great fortitude; no appearances of fear were to be perceived, but very evident signs of contrition and repentance".[17] His body was later publicly dissected at Surgeons' Hall, London.[1]

Aftermath

Hackman's case became famous, and The Newgate Calendar later noted that:[18]

This shocking and truly lamentable case interested all ranks of people, who pitied the murderer's fate, conceived him stimulated to commit the horrid crime through love and madness. Pamphlets and poems were written on the occasion, and the crime was long the common topic of conversation.

Horace Walpole remarked that the murder fascinated much of London during April 1779. At first, given Sandwich's position as First Lord of the Admiralty, a political motive was suspected. Not long before, Sandwich and Martha Ray had found themselves fleeing from Admiralty House, where a mob was rioting against the government and in particular against what it saw as the mistreatment of Admiral Keppel.[19]

The affair inspired Sir Herbert Croft's epistolary novel Love and Madness (1780), an imagined correspondence between Hackman and Martha Ray. In this, Hackman is dealt with sympathetically. He is represented as a man of sensibility suffering from an extreme case of unrequited love who descends into suicidal and homicidal despair, even to the point that the reader is invited to identify with Hackman rather than with his victim.[20]

Samuel Johnson and Topham Beauclerk debated whether Hackman had meant to kill only himself.[1] Johnson believed that the two pistols Hackman took with him to Covent Garden meant that he intended there to be two deaths.[21] Boswell himself (who had visited Hackman in prison) wrote that the case showed "the dreadful effects that the passion of Love may produce".[22][23]

In his Mind-Forg'd Manacles (1987), the social historian Roy Porter argues that Hackman was well aware of the madness of his passion.[24]

In The Luck of Barry Lyndon, Thackeray has his protagonist describe having met Hackman 'at one of Mrs Cornely's balls, at Carlisle House, Soho'.

Likenesses

A mezzotint of Hackman by Robert Laurie, after Robert Dighton, was published in 1779.[25] Another engraving of Hackman (artist unknown) was used as an illustration in The Case and Memoirs of the Late Rev. Mr James Hackman (1779).[1]

References

- Levy, Martin (2004), Love and Madness: The Murder of Martha Ray, Mistress of the Fourth Earl of Sandwich, Harper & Brothers ISBN 0-06-055975-6

- Brewer, John (2005), A Sentimental Murder: Love and Madness in the Eighteenth Century, Farrar, Straus and Giroux ISBN 0-374-52977-9

- Tankard, Paul (2014), Facts and Inventions: Selections from the Journalism of James Boswell, New Haven: Yale University Press ISBN 978-0-300-14126-9

Notes

- Rawlings, Philip, Hackman, James (bap. 1752, d. 1779), in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004) and online at Hackman, James (subscription required), accessed 16 March 2008

- "No. 11254". The London Gazette. 2 June 1772. p. 2.

- "No. 11703". The London Gazette. 21 September 1776. p. 1.

- "No. 11743". The London Gazette. 8 February 1777. p. 2.

- Rector of Wiveton at norfolkcoast.co.uk, accessed 16 March 2008

- The Case and Memoirs of the late Rev. Mr James Hackman (1779) p. 2

- "A Field Guide to the English Clergy' Butler-Gallie, F p140: London, Oneworld Publications, 2018 ISBN 9781786074416

- The Morning Post newspaper dated 9 April 1779

- Old Bailey Sessions Paper 209

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (accessed 13 May 2008), Trial of James Hackman. (t17790404-3, 4 April 1779).

- Tankard, Paul. "The Hackman Case." Facts and Inventions: Selections from the Journalism of James Boswell (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), Pp. 92-102.

- St. James's Chronicle newspaper, 17 April 1779; Tankard, op.cit., 95.

- The Genuine Life, Trial and Dying Words of the Rev. James Hackman, p. 17

- Public Advertiser newspaper, 12 April 1779

- Public Advertiser newspaper, 19 April 1779. See Tankard, 101.

- Public Advertiser newspaper, 21 April 1779. See Tankard, op.cit., 101-2.

- Jesse, J. H., George Selwyn and his Contemporaries, with Memoirs and Notes (new edition, in 4 volumes, 1882), vol. 4, p 85

- "James Hackman". The Newgate Calendar. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Novak, Maximilian E. & Mellor, Anne Kostelanetz (eds.), Passionate Encounters in a Time of Sensibility, (University of Delaware Press, 2000) p. 175

- Novak & Mellor, op. cit., Introduction, p. 22

- Boswell, James, Life of Johnson, ed. George Birkbeck Hill, rev. L. F. Powell, 6 v. (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1934) volume 3, p. 384

- Boswell, James, The Hypochondriack ed. Margery Bailey (Stanford University Press, 1928) 1:178-193

- Notes and Queries 3rd series, 4, pp 232–233

- Porter, Roy, Mind-Forg'd Manacles: a history of madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency (London, Athlone, 1987) p. 18

- James Hackman (1752-1779), Murderer at npg.org.uk, the web site of the National Portrait Gallery (accessed 17 March 2008)