James Achilles Kirkpatrick

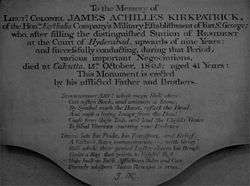

Lieutenant Colonel James Achilles Kirkpatrick (1764 – 15 October 1805) was the British Resident at Hyderabad from 1798 to 1805. He also built the historic Koti Residency in Hyderabad, a landmark and major tourist attraction.

James Achilles Kirkpatrick | |

|---|---|

James Achilles Kirkpatrick, an oil painting by George Chinnery. Circa 1805. | |

| Born | 1764 Fort St. George, Madras, India |

| Died | 15 October 1805 Calcutta, India |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Lieutenant Colonel British Resident at Hyderabad |

| Known for | Built the historic Koti Residency in Hyderabad, a landmark and major tourist attraction. Documented interracial love affair and marriage between him and Indian noblewoman Khair-un-Nissa Begum. |

| Spouse(s) | Khair-un-Nissa |

| Children | Kitty Kirkpatrick |

| Parent(s) |

|

Biography

James Achilles Kirkpatrick was born in 1764 at Fort St George, Madras.[1] He replaced his brother William and arrived as resident in Hyderabad in 1795 (according to William Dalrymple) as a "cocky young imperialist intending to conquer India". There he became thoroughly enamoured of Indo-Persian culture of Nizam's court, and gave up his English manner of dress in exchange for Persian costumes.[2]

Although a colonel in the British East India Company's army, Kirkpatrick wore Mughal-style costumes at home, smoked a hookah, chewed betelnut, enjoyed nautch parties, maintained a small harem in his zenanakhana. Kirkpatrick, born in India, educated in England, had Tamil as his first language, wrote poetry in Urdu, and added Persian and Hindustani to his linguistic armoury.[3]

With fluent Hindustani and Persian, he openly mingled with the elite of Hyderabad. Kirkpatrick was adopted by the Nizam of Hyderabad, who invested him with many titles: mutamin ul mulk ('Safeguard of the kingdom'), hushmat jung ('Valiant in battle'), nawab fakhr-ud-dowlah bahadur ('Governor, pride of the state, and hero').[4]

During the reign of George III, Kirkpatrick's hookah-bardar (hookah servant/preparer) was said to have robbed and cheated Kirkpatrick, making his way to England and stylising himself as the Prince of Sylhet. The man, presumably of Sylheti origin, was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of the King.[5]

Marriage

Kirkpatrick had an extremely private, Muslim marriage ceremony in which he wed a local Hyderabadi Sayyida noblewoman called Khair-un-Nissa, who was fourteen years old, not an unusual age for the marriage of girl of her social class. She was the granddaughter of Nawab Mahmood Ali Khan, the prime minister of Hyderabad. However, the marriage was not recorded and does not appear to have been legally valid; in his will he described the offspring of the relationship as his "natural" children, a polite euphemism for illegitimate children that a father recognized as his own offspring.[6] In his will, Kirkpatrick emphasized his devotion to Khair-un-Nissa, stipulating that he left her only a token bequest in light of the fact that in addition to her jewels, she possessed a large, landed fortune inherited from her father, leaving large fortunes to their two children instead. Before their father's unexpected, early death, at ages 3 and 5, the children had been sent to be reared by Kirkpatrick's relatives in England, as was usual among the British upper classes in India in that period. [7]

"Hashmat Jang was believed by some of his Muslim staff and by the bride's female relations to secretly embraced Islam before a Shi'a Mujtahid (cleric); he is said to have presented a certificate from him to Khair-un-Nissa Begum, who sent it to her mother." Towards the end of autumn of 1801, a major scandal broke out in Calcutta over Kirkpatrick's behaviour at the Hyderabad court.[8] A scandal arose due to the fact ethnically and racially mixed nature of the marriage.[9]

The conditions under which Kirkpatrick operated as Resident Minister were affected by Lord Richard Wellesley’s appointment as Governor-General of India. Wellesley was an imperialist determined to reduce the Nizam to subservience. Wellesley strongly disapproved of British-Indian liaisons.[10]

After Kirkpatrick died in Calcutta on 15 October 1805, Khair-un-Nissa, who was only 19 years old, had a brief love affair with Kirkpatrick's assistant, Henry Russell, who would become Resident in Hyderabad in 1810. After what Russell appears to have regarded as a brief fling, he abandoned Khair-un-Nissa who, with her reputation now ruined, was unable to prevent greedy relatives from taking over the valuable landed estates she had inherited from her father.[11] Russell married a half-Portuguese women. Although she, as a disgraced woman consequent to the love affair with Russell, she was not allowed by her family to return to Hyderabad for some years, with the death of a senior male relative she was eventually allowed to return, and died in Hyderabad on 22 September 1813 aged 27.[4]

Kirkpatrick and Khair-un-Nissa together had two children: a son, Mir Ghulam Ali Sahib Allum and a daughter, Noor-un-Nissa Sahib Begum. Their father had sent them to England to live with their grandfather Colonel James Kirkpatrick, in London and Keston, Kent, shortly before his own, unexpected death at a young age. The two children were baptised on 25 March 1805 at St. Mary’s Church, Marylebone Road, and were thereafter known by their new Christian names, William George Kirkpatrick and Katherine Aurora "Kitty" Kirkpatrick. William was disabled in 1812 after falling into a copper of boiling water and had to have an arm amputated;[12] he married and had three children but died in 1828 aged 27. Kitty was for a few years the love interest of the Scottish writer and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, then a young man of no fortune working as a tutor and an ineligible match for an heiress. She married Captain James Winslowe Phillipps and they had seven children. She died in Torquay, Devon, in 1889.[13]

Popular culture

A large part of White Mughals, a book by the historian William Dalrymple, concerns Kirkpatrick's relationship with Khair-un-Nissa.

Citations

- http://www.sumgenius.com.au/kirkpatrick_family_tree.htm

- Colonial Grandeur, The Hindu, 27 February 2005.

- – theartsdesk.com, best specialist journalism website, 4 September 2015

- Lolita of the Mughal Times - The Telegraph, 30 November 2002

- Colebrooke, Thomas Edward (1884). "First Start in Diplomacy". Life of the Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone. pp. 34–35.

- Dalrymple 2004, p. 6 "Finally, and perhaps most shockingly for the authorities in Bengal, some said that Kirkpatrick had actually, formally, married the girl, which meant embracing Islam, and had become a practising Shi'a Muslim."

- Dalrymple 2004

- White mischief - The Guardian, 9 December 2002

- Dalrymple 2004

- Dalrymple 2004

- Chatterjee, indrani (2004). Unfamiliar Relations: Family and History in South Asia. Rutgers University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0813533805.

- Dalrymple, William (2004). White Mughals. Penguin Books. pp. xx. ISBN 978-0-14-200412-8.

- East Did Meet West - 3 - Pakistan Link.com Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine - Dr. Rizwana Begum

References

- Dalrymple, William (2004). White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200412-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).