Jam band

A jam band is a musical group whose live albums and concerts relate to a fan culture that began in the 1960s with the Grateful Dead, who held lengthy improvisational "jams" during their concerts. These include extended musical improvisation over rhythmic grooves and chord patterns, and long sets of music which often cross genre boundaries.[1]

| Jam band | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | 1960s, California, United States |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms |

|

The jam band musical style spawned from the psychedelic rock movement of the 1960s. The Grateful Dead and The Allman Brothers Band became notable for their live improvisational jams and regular touring schedules, which continued into the 1990s. This influenced a new wave of jam bands in the late 1980s and early 1990s, who toured the United States with jam band-style concerts, such as Phish, moe., Edie Brickell & New Bohemians, Blues Traveler, Ozric Tentacles, Widespread Panic, Dave Matthews Band, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, Spin Doctors, The String Cheese Incident, Col. Bruce Hampton and the Aquarium Rescue Unit, Medeski Martin & Wood, The Black Crowes, Leftover Salmon, The Samples, Galactic, əkoostik hookah, and Lettuce. The jam band movement gained mainstream exposure in the United States in the early 1990s following the rise of Phish and the Dave Matthews Band as major touring acts and the dissolution of the Grateful Dead following Jerry Garcia's death in 1995.

Jam band artists often perform a wide variety of genres. While the seminal group the Grateful Dead are categorized as psychedelic rock,[2] by the 1990s the term "jam band" was applied to acts that incorporated genres such as blues, country music, contemporary folk music, funk, progressive rock, world music, jazz fusion, Southern rock, alternative rock, acid jazz, bluegrass, folk rock and electronic music into their sound.[1] Although the term has been used to describe cross-genre and improvisational artists, it also retains an affinity to the fan cultures of the Grateful Dead or Phish.[3]

A third generation of jam bands appeared in the late 1990s and early 2000s, many inspired by Phish and other acts of the second wave. These included Umphrey's McGee, Dispatch, Assembly of Dust, Gov't Mule, O.A.R., The Breakfast, The Derek Trucks Band, Agents of Good Roots, Benevento/Russo Duo, and My Morning Jacket. Additionally, groups such as The Disco Biscuits and Sound Tribe Sector 9 added electronic and techno elements into their performances, developing the livetronica subgenre. The early 2010s saw a fourth generation of jam bands, including Dopapod, Pigeons Playing Ping Pong, Twiddle, Moon Taxi and Spafford. Members of the Grateful Dead have continued touring since 1995 in many different iterations, such as The Dead, Bob Weir & Ratdog, Phil Lesh and Friends, Donna Jean Godchaux Band, 7 Walkers, Furthur and Dead & Company. Members of other jam bands also often perform together in various configurations and supergroups, such as Tedeschi Trucks Band, Oysterhead and Dave Matthews & Friends.

A feature of the jam band scene is fan taping or digital recording of live concerts. While many other styles of music term fan taping as "illegal bootlegging", jam bands often allow their fans to make tapes or recordings of their live shows. Fans trade recordings and collect recordings of different live shows because improvisational jam bands play their songs differently at each performance. By the 2000s, as internet downloading of MP3 music files became common, downloading of jam band songs became an extension of the cassette taping trend. Bands are also distributing their shows online, sometimes within days or hours.

History

Modern use and definition

In the 1980s the Grateful Dead's fan base included a large core group which followed their tours from show to show. These fans (known as "Deadheads") developed a sense of community and loyalty. In the 1990s, the band Phish began to attract this fan base. The term "jam band" was first used regarding Grateful Dead and Phish culture in the 1990s. In 1998 Dean Budnick wrote the first book devoted to the subject, entitled Jam Bands.[4] He founded Jambands.com later that year and he is often credited with coining the term.[5] However, in his second book on the subject, 2004's Jambands: A Complete Guide to the Players, Music & Scene, he explains that he only popularized it.[6]

Rolling Stone magazine asserted in a 2004 biography that Phish "was the living, breathing, noodling definition of the term" jam band, in that it became a "cultural phenomenon, followed across the country from summer shed to summer shed by thousands of new-generation hippies and hacky-sack enthusiasts, and spawning a new wave of bands oriented around group improvisation and super-extended grooves."[7] Another term for "jam band music" used in the 1990s was "Bay Rock". It was coined by the founder of Relix magazine, Les Kippel, as a reference to the 1960s San Francisco Bay Area music scene, which included the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape, among many others.

By the late 1990s, the types of jam bands had grown so that the term became quite broad, as exemplified by the definition written by Dean Budnick, which appeared in the program for the first annual Jammy Awards in 2000 (Budnick co-created the show with Wetlands Preserve[8] owner Peter Shapiro).

What Is a Jam Band? Please cast aside any preconceptions that this phrase may evoke. The term, as it is commonly used today, references a rich palette of sounds and textures. These groups share a collective penchant for improvisation, a commitment to songcraft and a propensity to cross genre boundaries, drawing from a range of traditions including blues, bluegrass, funk, jazz, rock, psychedelia and even techno. In addition, the jam bands of today are unified by the nimble ears of their receptive listeners.[1]

Although in 2007 the term may have been used to describe nearly any cross-genre band, festival band, or improvisational band, the term retains an affinity to Grateful Dead-like bands such as Phish.[3] Andy Gadiel, the initial webmaster of Jambands.com who went on to found JamBase, states in Budnick's 2004 edition of Jambands that the music "...had a link that would not only unite bands themselves but also a very large community around them."[9]

Ambiguity

By the late 1990s use of the term jam band became used retroactively in jam band circles for bands such as Cream[10] who for decades were categorized as a "power-trio" and "psychedelic rock" and who when active were largely unrelated to the Grateful Dead---but whose live concerts usually featured several extended collective improvisations. In his October 2000 column on the subject for jambands.com, Dan Greenhaus attempted to explain the evolution of a jam band as such:

"At this point, what you sing about, what instruments you play, how often you tour and how old you are has become virtually irrelevant. At this point, one thing is left and, ironically, after all these years, it’s the single most important place one should focus on; the approach to the music. And the jamband or improvisational umbrella, essentially nothing more than a broad label for a diverse array of bands, is open wide enough to shelter several different types of bands, whether you are The Dave Matthews Band or RAQ."[11]

The Jammy Awards have had members of non-jamming bands which were founded in the 1970s and were unrelated to the Grateful Dead perform at their show such as new wave band The B-52's.[12] The Jammys have also awarded musicians from prior decades such as Frank Zappa.[13]

Debate

Some artists such as The Derek Trucks Band are known for resisting the jam band label. Dave Schools of Widespread Panic said in an interview, "We want to shake free of that name, jam band. The jam band thing used to be the Grateful Dead bands. We shook free of that as hard as we could back in 1989. Then Blues Traveler came on the scene. All together, we created the H.O.R.D.E. tour, which focused a lot of attention on jam bands. Then someone coined the term jam bands. I'd rather just be called retro. When you pigeonhole something, you limit its ability to grow and change."[14] An example of a prior-era band that gained the label "jam band" through an active affiliation with the 1990s jam band culture is The Allman Brothers Band. However, Gregg Allman has been quoted as recently as 2003 by his fellow band member Butch Trucks in stating that rather than being a jam band The Allman Brothers are "a band that jams".[15]

Although Trucks suggests that this is only a difference of semantics, the term has a recent history for which it is used exclusively. An example of this discernment is the acceptance of Les Claypool as jam band in the year 2000. Though famed from an entire decade with Primus (a band that jams) and solo works, it was in creating the Fearless Flying Frog Brigade with members of Ratdog and releasing Live Frogs Set 1 that as Budnick has stated "marked [Claypool's] entry into [the jamband] world."[16] Budnick has been both editor-in-chief of Jambands.com and executive editor of Relix Magazine.[17]

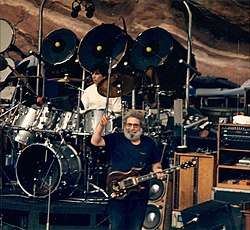

Mid-1960s–Mid-1980s: The Grateful Dead & The Allman Brothers Band

The band that set the template for future jam bands was the Grateful Dead, founded in 1965 by legendary San Francisco-based guitarist Jerry Garcia. Although their studio albums enjoyed only modest success, and they were never an AM-radio favorite, "The Dead" attracted an enormous cult following, mainly on the strength of their live performances (and live albums). Drawing inspiration from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band's improvisational 1966 epic "East-West" and Eric Clapton's short-lived (but influential) supergroup Cream, the band specialized, in concert, in improvisational jamming. They played long two-set shows, and gave their fans a different experience every night, with varying setlists, evolving songs, creative segues and extended instrumentals. Their loyal fans ("Deadheads") followed them on tour from city to city, and a hippie subculture developed around the band, complete with psychedelic clothes, a black market in concert-related products, and drug paraphernalia. The band toured regularly for nearly three decades, except for a hiatus from 1974-1976. The eventual heirs to this "Shakedown Street" fan culture, Phish, formed in 1983 at the University of Vermont in Burlington. They solidified their lineup in 1985, and began their career with a few Grateful Dead songs in their repertoire.

The Allman Brothers Band were also considered a jam band, particularly during the Duane Allman era. Songs such as "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed" and "Whipping Post", which were 5–7 minutes long on their studio albums, became 20 minute jams at concerts. The Allmans even performed a 34-minute jam with the Grateful Dead in 1970. Their 1972 album Eat A Peach included "Mountain Jam", a 34-minute instrumental that was recorded live. The 1971 live album At Fillmore East featured a 24-minute version of "Whipping Post", and a 20-minute version of Willie Cobbs' "You Don't Love Me".

Mid-1980s–1990

The Grateful Dead continued to grow their fanbase to nearly unmanagable levels in the second half of the 1980s. The party atmosphere of Grateful Dead shows drew in a new generation of fans, especially after they released "Touch of Grey" which surprisingly became a hit song on MTV in 1987. They eventually began playing football stadiums, where fans turned the parking lots into campgrounds.

In the mid-1980s the bands Phish, Edie Brickell & New Bohemians, Blues Traveler, Ozric Tentacles, Widespread Panic, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, Spin Doctors, Col Bruce Hampton and Aquarium Rescue Unit, began touring with jam band-style concerts. Their fame increased in the early 1990s. Widespread Panic originated in Athens, GA, when Michael Houser and John Bell started playing together. In 1986, after Todd Nance and Dave Schools joined them, the band played their first show as "Widespread Panic". Blues Traveler and the Spin Doctors came from the same scene, playing Jam-friendly venues and festivals.

In some cases, their improvisations have taken a backseat to more polished material, which may be due to their crossover commercial successes, MTV videos, and mainstream radio airplay. Most notable in pre-jam band history was the obvious influence of the Grateful Dead. By the end of the decade, Phish had signed a recording contract with Elektra Records, and transformed from a New England/Northeast-based band into a national touring band (see: Colorado '88). While they may not have had Phish's commercial success, "With its fusion of southern rock, jazz, and blues, Widespread Panic has earned renown as one of America's best live bands. They have often appeared in Pollstar's "Concert Pulse" chart of the top fifty bands on the road, and they have performed more than 150 live dates a year."[18]

1990–1995

In the early 1990s, a new generation of bands was spurred on by the Grateful Dead's touring and the increased exposure of The Black Crowes, Phish, Widespread Panic and Aquarium Rescue Unit. Phish was building a large fan base and innovating new concepts into their shows. At the same time, the inception of the Internet provided a medium for fans to discuss these bands and their performances as well as to view emerging concepts.[19]

Phish (along with the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, and The Beatles) was one of the first bands to have a Usenet newsgroup. To capitalize on this, they started trying out new theatrics at shows, such as the Big Ball Jam from 1992–1994, the Secret Language created in 1992 (03/06/92 - Portsmouth, NH),[20] and the Audience Chess match, that lasted the entire 1995 tour. A rapidly expanding concert-going market in the early 1990s saw Phish playing mid-sized amphitheaters already in 1993 and 1994, with the band really starting to build momentum. The band also earned chances to play at various large venues, such as Madison Square Garden, by 1994's end. Many new bands were formed in the blooming scene. These were the first new bands to actually be called "jam bands", including ekoostik hookah, Dispatch, Gov't Mule, One-Eyed Jack, Leftover Salmon, Jambay,[4] moe., Rusted Root and The String Cheese Incident.

During the summer of 1995 shortly after the now famous Deer Creek[21] gate crash, Grateful Dead guitarist and frontman Jerry Garcia died, ending the group's thirty years of prominence. The surviving members created a band called The Other Ones (they used the name "The Dead" for some tours in the following decade). During the same period, Phish rose to prominence, and bands such as String Cheese Incident and Blues Traveler became successful. Many stranded Deadheads moved over to Phish scene, which was at the time the top touring Jam band behind the Grateful Dead. Phish began a new chapter in their career after the demise of the Grateful Dead, as the band became more popular, and more recognized as mainstream, over the next five years.

1996–2008: rise of Phish and music festivals

Phish's popularity exploded after the demise of the Grateful Dead. In spite of being ignored by most media, they drew large crowds to amphitheaters and arenas throughout the late 1990s. During this period, the Jam band scene gained more recognition, with Phish identified as a leader. After a short hiatus from 2000–2002, Phish resumed a heavy touring schedule in 2003. By 2004, a variety of issues led lead singer/guitarist Trey Anastasio to break up the band.

Phish held their first major music festival on 16 and 17 August 1996 in Plattsburgh, NY, which drew 70,000 fans, and featured seven sets of music. This was the largest concert of the year, and Phish followed that up with similar-sized festivals in the Northeast in 1997, 1998, and 1999. Between 30 December 1999, and 1 January 2000, Phish held an enormous festival named "Big Cypress" in southern Florida, which concluded with an eight-hour set to begin the new millennium. The final shows before their breakup in 2004 were at the Coventry Festival in Vermont. As of 2015, Phish has played a total of ten multi-day camping festivals, the most recent being Magnaball in Watkins Glen, NY from Aug. 21-23.[22] The success of these festivals led other bands to start their own festivals, notably the Disco Biscuits, who held their first Camp Bisco in 1999, and moe., which began its annual moe.down festivals in 2000.

A more significant consequence of Phish's reinvention of large-scale festivals can be seen founding of the Bonnaroo festival in 2002. This multi-band, multi-day festival in Manchester, Tennessee, which annually draws close to 100,000 music fans, started as a jam band-focused festival. Over time, bands from many genres have performed at Bonnaroo, but the similarities to Phish's festivals are still apparent. Other music festivals have sprung up all over the country, and this has become an important part of the music industry, as bands seek ways to compensate for the deteriorating compact disc market.

2004–present

After Coventry, many Phish fans found themselves in a predicament similar to that Deadheads faced almost a decade previously. With no more Phish to follow around, the hundreds of thousands of Phish fans began investing time in the other top jam band acts of the day. This gave newer bands such as STS9, Disco Biscuits, and Umphrey's McGee a greater opportunity to grow their fanbase. These bands have steadily increased their popularity, but so far, no jam band has reached Phish's attendance levels. Phish never reached the Grateful Dead's peak attendance levels, so the fragmentation of the jam band scene has been a long term trend. Phish announced on 1 October 2008 that they would return to the stage in March 2009 at Hampton Coliseum. Following their reunion, Phish resumed their status as one of the top concert draws in the United States. The band were one of the highest grossing touring musical artists of both 2016 and 2017, and their 13-night "Baker's Dozen" run at Madison Square Garden in 2017 grossed $15 million.[23][24]

Widespread Panic became the top jam band (by attendance) after Phish broke up in 2004. Their southern jam style brings out large crowds to amphitheaters and large indoor venues. Bringing in Jimmy Herring in 2006, a virtuoso jam band veteran guitarist, added a fresh edge to their huge catalog of songs.

moe. has maintained a tightly-knit fanbase through this period. Their enduring popularity is supported by steady touring, including frequent festival appearances. String Cheese Incident has mixed bluegrass and electronic sounds to build a devoted fanbase as well. SCI has significantly reduced their touring schedule in recent years, giving each of their shows a special reunion vibe.

Many of today's jam bands have brought widely varied genres into the scene. A jam band festival may include bands with electronic, folk rock, blues rock, jazz fusion, psychedelic rock, southern rock, progressive rock, acid jazz, hip hop, hard rock, reggae, and bluegrass sounds. The electronic trend has been led by such bands as The Disco Biscuits, Sound Tribe Sector 9 (STS9), Lotus, EOTO, The New Deal, and Dopapod. Bands like moe., Umphrey's McGee, Lettuce, Assembly of Dust, The Heavy Pets and The Breakfast have carried on the classic rock sound mixed with exploratory jams. Members of the Grateful Dead have continued touring in many different configurations as The Dead, Bob Weir & Ratdog, Phil Lesh and Friends, 7 Walkers, and Furthur.

The British IDM band Autechre became known as "the first digital jam band" after their 4-hour long 2016 album set elseq 1-5. Blending jam band elements with those of electronica is known as "jamtronica" or "livetronica" (a portmanteau of the terms "live music" and "electronica"). [25][26][27] Bands includes The Disco Biscuits, STS9 (Sound Tribe Sector 9)[28], and The New Deal[29] (although STS9 guitarist Hunter Brown has expressed basic reservations about the "livetronica" label, explaining that "it's a really vague term to describe a lot of bands," he did cite Tortoise as stylistic precursors).[26] Entertainment Weekly also identified Prefuse 73, VHS or Beta, Lotus, Signal Path, MFA, and Midwest Product as notable livetronica groups.[25]

Jam scene

The contemporary jam scene has grown to encompass bands from a great diversity of musical genres. A 2000-era genre of jam-band music uses live improvisation that mimics the sounds of DJs and electronica musicians and has been dubbed "trancefusion" (a fusion between trance music and rock and roll). Progressive bluegrass and progressive rock are also quite popular among fans of jam bands. In the early 2000s, the jam scene helped influence the touring patterns and approach of a new wave of indie bands like Vampire Weekend, MGMT, Interpol and The National. [30]

Hundreds of jam-based festivals and concerts are held throughout the United States every year. The Bonnaroo Music Festival, held each June in Tennessee continues to provide a highly visible forum for jam acts, even though this festival has attracted many different genres during its decade-plus history. As with other music scenes, devout fans of jam bands are known to travel from festival to festival, often developing a family-like community. These committed fan groups are often referred to by the derogatory terms "wookies" or "wooks."[31]

Taping

Jam bands often allow their fans to make tapes or recordings of their live shows, a practice which many other musical genres call "illegal bootlegging". The Grateful Dead encouraged this practice, which helped to create a thriving scene around the collecting and trading of recordings of Grateful Dead live performances. Most of the live shows on the Grateful Dead's 30 years of touring were recorded. It was probably the trading of recordings of Grateful Dead shows which built the band's fan base.

Starting in 1984,[32] the band recognized the fact that people were already "unofficially" taping their shows, so they started to sell taper tickets for a taper's section which allowed the tapers to bring their own microphones and tape decks to record with, as well as wrangle the tapers into one area of the venue so to keep them from interfering with other concertgoers. This type of encouragement has spread to nearly all of the jam bands. Some jam band enthusiasts argue that if a band does not allow fans to tape their live shows, this band is not actually a jam band in the Grateful Dead tradition.

Fans trade recordings and collect recordings of different live shows because improvisational jam bands play their songs differently at each performance and generally mix up their set lists so as to encourage fans to see them on multiple nights. Fans collect various versions of their favorite songs and actively debate which is the "best version" of any particular song, keeping lists of notable versions of those songs.

They keep track of how many times a specific song has been played and note the frequency of performances of certain songs, and note the relative rarity or commonality of its performance during certain years. This increases the momentousness of a rare song being dusted off and played live, or played for the first time.[33] Some bands play with this phenomenon by throwing short little "teases" into their sets. Playing, for example, a few bars of a famous cover song or hinting at a popular jam and then either never getting around to playing the song, or coming back to it after an extended jam. The use of segues to blend strings of songs together is another mark of a jam band, and one which makes for treasured tapes.[34]

Music downloading

By the 2000s, as internet downloading of MP3 music files became common, downloading of jam band songs became an extension of the cassette taping trend. Archived jam band downloads are available at various websites, the most prominent ones being etree and the Live Music Archive, which is part of the Internet Archive.

More bands have been distributing their latest shows online. Bands such as Phish, Widespread Panic, The String Cheese Incident, Gov't Mule, ekoostik hookah, Umphrey's McGee, Dopapod, Lotus, and The Disco Biscuits have been offering digital downloads within days, or sometimes hours, of concerts. The Grateful Dead have begun to offer online, digital download only, live releases from their archives as well. While there is some obvious conflict of interest between the "free and open trading of shows" and artists packaging and selling the same shows for money, a dynamic equilibrium has been reached where die-hards trade and others are happy to pay for the convenience.

Some venues offer kiosks where fans may purchase a digital recording of the concert and download it to a USB flash drive or another portable digital storage device. Some bands, including The Allman Brothers, Zac Brown and O.A.R. offer "Instant Lives", which are concert recordings made available for purchase on Compact Disc or USB Flash Drive shortly after the show ends. Most major music festivals also offer digital live recordings at the event. Several vendors such as Instant Live[35] by Live Nation and ADERRA[36] offer this remote recording service for instant delivery. Even though these shows are freely traded in digital format, "official" versions are still bought by fans for the graphics, liner notes, and packaging.

Venues and festivals

In the August 2006 issue of Guitar One on jam bands, the following places were referred to as the "best places to see jam music": Red Rocks Amphitheatre, Red Rocks Park, Denver, CO; The Gorge Amphitheatre, George, Washington; High Sierra Music Festival, Quincy, CA; Saratoga Performing Arts Center, Saratoga Springs, NY; The Greek Theater, Berkeley, CA; Bonnaroo Music Festival (Bonnaroo has become increasingly mainstream in recent years, and has seen a shift in fan base), Manchester, TN; The Warfield Theater, San Francisco, CA; Higher Ground, Burlington, Vermont, Nelson Ledges Quarry Park, Garrettsville, Ohio; and the Jam in the Dam in Amsterdam.

One way to see many jam bands in one place is by going to a jam band-oriented music festival. Some popular festivals that include jam bands are: Bonnaroo in Manchester, Tennessee; Gathering of the Vibes in Bridgeport, Connecticut; Rothbury Festival in Rothbury, Michigan (now known as Electric Forest Festival; The aforementioned High Sierra Music Festival in Quincy, California; All Good; Wakarusa Music and Camping Festival outside Fayetteville, AR (now defunct); Mountain Jam (festival) in Hunter Mt, New York; Telluride Bluegrass Festival in Colorado; Lockn' Festival in Arrington, Virginia; The Werk Out Music Festival in Thornville, Ohio; and Summer Camp Music Festival in Chillicothe, Illinois.

Business model and copyright law

Mark Schultz[37] described fundamental differences between the business models of jam bands and the mainstream music industry: "Jamband fans seem to view band management as people who work for the artists and themselves as part of a community that includes the band. Mainstream music fans, on the other hand, often portray band management as part of a ruthless industry that merely employs musicians and mistreats fans and musicians alike." He relates this to the work of Tom R. Tyler, who described "two alternative strategies for effective law enforcement:

- Deterrence: effective but inefficient

- Process-based: efficient and effective."

Jam bands encourage fans to bring recording equipment to live performances and give away copies of what they record. This practice may increase the sizes of their audiences and the total revenue received from concerts and sale of recorded music. The fans reciprocate the generosity of the jam bands by helping enforce the copyright rules that the bands write, consistent with Tyler's "process-based" law enforcement. Schultz said the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) seems to call most fans pirates intent on stealing their music. Thus, the mainstream music industry attempts to maximize their revenue through deterring illegal sharing of music. [For more on the approach of the mainstream music industry to copyrights, see Free Culture (book).]

Schultz said that the key concept here is reciprocity: Fans treated with generosity and respect by jam bands tend to be more loyal even to the point of helping enforce the copyrights the jam bands claim. Fans similarly reciprocate the hostility they perceive in the anti-piracy lawsuits filed by the mainstream recording industry. It's not clear which business model is most remunerative for music industry managers, but Schultz insisted that jam bands tend to have more loyal fans, and the mainstream music industry might benefit from treating their fans with more respect, following the model of jam bands.

List of jam bands

See also

References

- "What is a jam band?". Jambands.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- The Grateful Dead Archived 15 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Britannica Online, Retrieved 17 September 2007

- Relix, all issues.

- Budnick, Dean (1998). Jam Bands: North America's Hottest Live Groups Plus How to Tape and Trade Their Shows. ECW Press. 1998. p. 68. ISBN 9781550223538. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

Jambay.

- Peter Conners JAMerica: The history of the jam band and festival scene, Da Capo 2013 p. 68,70

- Jambands, Dean Budnick, Backbeat Books, 2003, p. 241, JAMerica, p.79.

- "Phish Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Alex Bereson A Night Out With: Peter Shapiro; Death of a Deadhead Dive nytimes.com 5 August 2001, Retrieved 2 February 2009

- Jambands, Dean Budnick, Backbeat Books, 2003, p. 243.

- Cream 2005 Archived 15 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Pat Buzby, JamBands.com, 13 November 2005, Retrieved 10 September 2007

- The Jamband Backlash: Where did Things Go Wrong? Archived 20 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Dan Greenhaus, Jambands.com, Oct 2005

- Anastasio, Phish Win At Jammy Jam Archived 15 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Jon Wiederhorn, MTV News, 4 October 2002 Retrieved 4 October 2007

- My Morning Jacket Lead Jammys Archived 10 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Charley Rogulewski, Rolling Stone, 24 Feb 2006 Retrieved 4 October 2007

- Bob Makin Widespread Panic: Against the Grain Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine jambands.com October 1999

- Jambands, Dean Budnick, Backbeat Books, 2003, p. XII

- Jambands, Dean Budnick, Backbeat Books, 2003, pp 248-9

- Melinda Newman "Jam Bands Weather Economic Uncertainty With Ingenuity and Loyal Fans," Washington Post 9 August 2009, Blake Gernstetter "Relix Remix: Music Mag Relaunches Under New Ownership" Mediabistro.com, 4 May 2009 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Widespread Panic". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Santos, Rafael (30 October 2016). "The Internet gives publicity for new and emerging concepts". prezi.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090129101825/http://www.mockingbirdfoundation.org/setlists/1992.html. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "7/5/95 Letter from the Grateful Dead". hake.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Phish festivals#Magnaball

- "Phish Tops Billboard's "Hot Tours" List After Successful MSG New Year's Run". L4LM. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Phish, Dead & Company, and DMB Among Top 50 Grossing Tours Of 2016". L4LM. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Drumming, Neil (21 February 2005). "Pushing Your Buttons". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- Harrington, Jim (14 April 2005). "Be it tie-dye or techno, STS9 has a good time". Oakland Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- Sixty second lesson on Livetronica|EW.com

- Three Must-See Acts This Week - 01/23/2019 - SF Weekly

- Eisen, Benji. "Back to the Future: An Oral History of Livetronica". Relix.com. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Greenhaus, Mike https://jambands.com/mike-greenhaus-the-greenhaus-effect/2009/06/09/smells-like-hippie-spiritrelix-uncovers-indie-rocks-true-jamband-roots/ Jambands.com

- "How to Spot a Festival Wookie". vice.com. 6 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Official Grateful Dead website". Dead.net website. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- One such event was the Grateful Dead's playing of "Unbroken Chain," a song bass-player Phil Lesh penned (and sang), and a fan-favorite from the Dead's much-loved From The Mars Hotel (1974) LP, in their final year together. The re-emergence of their archetypal jam song "Dark Star" after years of absence from the repertoire is another such event.

- Fans will frequently wax rhapsodic about performances such as "that one show where Phish segued out of 'Fee', into 'Stash', into 'You Enjoy Myself', and then back into 'Stash' again."

- "Instant Live - It's better live | Live Nation Store". Store.livenation.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "Aderra Media - Live Music Recorded to MicroSD cards and Flash Drives CONCERT USB-FREE DOWNLOADS". Aderra.net. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Schultz, Mark F. (2006). "Fear and Norms and Rock & Roll: What Jambands Can Teach Us about Persuading People to Obey Copyright Law". Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 21: 651–728. SSRN 864624.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jam bands. |