Jailhouse Rock (film)

Jailhouse Rock is a 1957 American musical drama film directed by Richard Thorpe and starring Elvis Presley, Judy Tyler, and Mickey Shaughnessy. Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and dramatized by Guy Trosper from a story written by Nedrick Young, the film is about a young man sentenced to prison for manslaughter who is mentored in music by his prison cellmate who realizes his musical abilities. After his release from jail, while looking for a job as a club singer, the young man meets a musical promoter who helps him launch his career. As he develops his musical abilities and becomes a star, his self-centered personality begins to affect his relationships.

| Jailhouse Rock | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Theatrical release poster by Bradshaw Crandell | |

| Directed by | Richard Thorpe |

| Produced by | Pandro S. Berman |

| Screenplay by | Guy Trosper |

| Story by | Nedrick Young |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Jeff Alexander |

| Cinematography | Robert J. Bronner |

| Edited by | Ralph E. Winters |

Production company | Avon Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] |

| Box office | $4 million[1] |

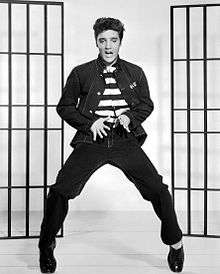

The wife of producer Pandro S. Berman convinced him to create a film with Presley in the role. Berman delegated the casting to Benny Thau, head of the studio and Abraham Lastfogel, the then president of William Morris Agency. Berman hired Richard Thorpe, who was known for shooting productions quickly. The production of Jailhouse Rock began on May 13, 1957, and concluded on June 17 of that year. The dance sequence to the film's title song "Jailhouse Rock" is often cited as "Presley's greatest moment on screen".

Before pre-production began, songwriters Mike Stoller and Jerry Leiber were commissioned to integrate the film's soundtrack. In April, Leiber and Stoller were called for a meeting in New York City to show the progress of the repertoire. The writers, who had not produced any material, toured the city and were confronted in a hotel room by Jean Aberbach, who locked them into their hotel room by blocking the hotel room door with a sofa until they wrote the material. Presley recorded the soundtrack at Radio Recorders in Hollywood on April 30 and May 3, with an additional session at the MGM Soundstage on May 9. During post-production, the songs were dubbed into the films scenes, in which Presley mimed the lyrics.

Jailhouse Rock premiered on October 17, 1957 in Memphis, Tennessee and was released nationwide on November 8, 1957. It peaked at number 3 on the Variety box office chart, and reached number 14 in the year's box office totals, grossing $4 million. Jailhouse Rock earned mixed reviews, with most of the negative reception directed towards Presley's persona. In 2004, the film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry and was deemed "culturally, aesthetically or historically significant."[2][3] On its January 28, 2019 edition, the Ultimate Classic Rock website named it the best rock movie of 1957.

Plot

Construction worker Vince Everett (Elvis) accidentally kills a drunken and belligerent man in a barroom brawl. He is sentenced to two years in the state penitentiary for manslaughter. His cellmate, washed-up country singer Hunk Houghton (Shaughnessy) who was jailed for bank robbery, starts teaching Vince to play the guitar after hearing Vince sing and strum Hunk's guitar. Hunk then convinces Vince to participate in an upcoming inmate show, which is broadcast on nationwide television. Vince receives numerous fan letters as a result; but out of apparent jealousy, Hunk ensures they are not delivered to Vince. Hunk then convinces Vince to sign a "contract" to become equal partners in his act. Meanwhile, during an inmate riot in the mess hall, a guard shoves Vince, who retaliates by striking the guard. As a result, the warden orders Vince to be lashed with a whip. Afterwards, it was discovered that Hunk attempted to bribe the guards to drop the punishment, but to no avail.

Upon Vince's release 20 months later, the warden gives Vince his fan mail. Hunk then promises Vince a singing job at a nightclub owned by a friend, where Vince meets Peggy Van Alden (Tyler), a promoter for pop singer Mickey Alba. Vince is surprised when the club owner denies him a job as a singer but offers him a job as a bar boy. Undeterred, Vince takes the stage when the house band takes a break and starts singing "Young and Beautiful." But one of the customers laughs obnoxiously throughout the performance, enraging Vince, who smashes his guitar on the customer's table and leaves the club. Peggy follows Vince and persuades him to record a demo so that he can listen to himself sing. Vince records "Treat Me Nice" which Peggy takes to Geneva Records. The manager seems unimpressed, but he reluctantly agrees to play the tape for his boss in New York. The next day, Peggy informs Vince that the song has been sold. She then takes him to a party at her parents' home, but Vince leaves after he offends a guest he mistakenly believes is belittling him. (The guests were talking about progressive jazz.) Angry and offended, Peggy confronts Vince, who kisses her brutally. Peggy resentfully calls the gesture "cheap tactics," to which Vince replies, "Them ain't tactics, honey; it's just the beast in me."

Later, Vince and Peggy visit a local record store to check out Vince's new single, but they are shocked to discover that the Geneva Records manager gave the song to Mickey Alba, who recorded and released the song himself, thereby stealing Vince's song. Outraged, Vince storms into the label's office and confronts the manager, violently slapping him around. To avoid making the same mistake twice, Vince suggests that he and Peggy should form their own label. They do, naming the new label Laurel Records and hiring an attorney, Mr. Shores (Vaughn Taylor), to oversee their business. Vince then records "Treat Me Nice" and begins pitching it, but it is universally rejected. Peggy convinces her friend, disc jockey Teddy Talbot (Dean Jones), to air the song. He does, and it becomes an immediate hit. Later that evening, Vince asks Peggy out to celebrate the success of his new single, but is disappointed when he learns that she has accepted a dinner date for that evening with Teddy.

Meanwhile, Vince makes arrangements for another television show. During a party, Hunk visits him after being paroled and persuades Vince to give him a spot on the upcoming show. Prior to taping, Vince rehearses "Jailhouse Rock" in a stylized cell block (a performance Elvis himself choreographed). Hunk's number is cut because of his outdated music style. Afterwards, Vince informs Hunk that according to his lawyer, the above-mentioned "contract" they signed in prison was worthless. However, as a consolation, and never forgetting that Hunk tried to intercede on his behalf when he was punished for striking the prison guard, Vince offers Hunk a job with his entourage for a fee equal to ten percent of Vince's annual gross, which Hunk accepts.

Within a few months, Vince officially becomes a star. However, Peggy is no longer on speaking terms with Vince, as his success has made him arrogant. Vince then signs a movie deal with Climax Studios. The studio head asks him to spend the day with Sherry Wilson (Jennifer Holden), the studio's new leading lady, for publicity purposes. The conceited actress is less than thrilled with her co-star at first; but she eventually falls in love with Vince after shooting a kissing scene, saying that she's "come all unglued" (indicating that she's no longer "stuck up").

Meanwhile, Hunk grows tired of Vince's self-centered attitude. When Peggy shows up unexpectedly at another of Vince's parties, Vince is happy to see her at first but becomes upset when she says the purpose of her visit is to talk about business. Mr. Shores then approaches Vince with an offer from Geneva Records to purchase Laurel Records and sign him to a rich contract. Peggy refuses to sell, but Vince announces that he will close the deal since he owns a controlling interest, which deeply devastates Peggy. Enraged by Vince's attitude—and his treatment of Peggy—Hunk provokes Vince to fight, who refuses to fight back. Hunk delivers several hard blows with the last one striking Vince in the throat, endangering his voice and therefore his singing ability. Vince is then rushed to a hospital, where he forgives Hunk and realizes he loves Peggy and she loves him. After being released from the hospital, Vince's doctor informs him that his vocal cords are fully recovered, but Vince is worried that his voice might have been affected. To test it, he sings "Young and Beautiful" to Peggy, which reassures him that his fears are unfounded.

Cast

- Elvis Presley as Vince Everett, a prisoner who, after being released, becomes a star for his singing talent.[4] Producer Pandro S. Berman's wife convinced him to make a film with Presley starring in the leading role. Berman contacted Presley's manager, Colonel Thomas Parker, and asked if he could send Presley or Parker the script to read it. Parker was uninterested and denied the request. Berman asked Parker under which conditions would he take the project, to which Parker replied that he was only interested in the music score of the movie and owning the rights for record sales and publishing royalties.[5][6] Presley's payment was settled at US$250,000 and 50% of the royalties from the distribution of the movie.[7]

- Judy Tyler as Peggy Van Alden, a music promoter who helps Vince build his career and eventually becomes his lover.[4] Tyler was previously known for her part as Princess Summerfall Winterspring in the television show Howdy Doody and her role as Suzy in the Broadway musical Pipe Dream (1955).[8][9] Tyler took a three-month leave of absence from Howdy Doody to shoot the movie. Tyler and her husband were both killed in a car crash on July 3, just days after production of the movie was completed and before its premiere.[8] Presley was so devastated over her untimely death that he refused to watch the film.

- Mickey Shaughnessy as Hunk Houghton, Vince's cellmate and a former country and western singer. He teaches Vince to improve his guitar skills, and after his release from jail becomes Vince's assistant.[4] Shaughnessy was known for his role as Leva in From Here to Eternity (1953).[10] He was also a comedian; Variety reported before the production of the film that during one of his shows in Omaha, Nebraska, Shaughnessy performed a forty-five-minute routine that derided Presley. Elaine Dundy, author of the book Elvis and Gladys (1985), considered that his casting was an "odd choice", and a product of Berman's disinterest and his decision to delegate the casting of the actors.[11]

- Vaughn Taylor as Mr. Shores, an attorney whom Vince and Peggy hire to manage Vince's financial affairs.[12]

- Jennifer Holden as Sherry Wilson, a starlet of Climax Studios and Vince's co-star.[13] The movie was Holden's debut; she auditioned for the role at MGM in May 1956 and was selected immediately for the role. She studied drama with Lillian Roth and participated in a small role in a play at the Palace Theatre in New York City.[14]

- Dean Jones as Teddy Talbot, a disc jockey who plays Vince's debut record as a favor to Peggy. Jones himself was formerly a blues singer, and he was coached for the role by disc jockeys Ira Cooke and Dewey Phillips.[15]

- "Jailhouse Rock" co-writer Mike Stoller (of the Leiber and Stoller songwriting partnership) and Presley's regular band during that period—Scotty Moore, Bill Black and D. J. Fontana—appeared as Vince's band throughout the film, but were uncredited.[16]

- Paul Winchell as convict

Production

Jailhouse Rock was Presley's third film and his first for MGM.[17] It was filmed at MGM Studios (now Sony Pictures Studios) in Culver City, California.[7] Filmed in black-and-white, the film was the first production that MGM filmed with the recently developed 35 mm anamorphic lens by Panavision.[17][18] The film was originally titled The Hard Way, which was changed to Jailhouse Kid before MGM finally settled on Jailhouse Rock.[17] It was not listed with the studio's planned releases for the year, which it published in Variety magazine, because it was based on an original story by Nedrick Young, a blacklisted writer. In addition, the studio traditionally did not produce any original scripts that were not adaptations of already-successful works such as books or theater plays.[11][19] During the production of the movie, Pandro Berman's attention was centered on another of his productions, the 1958 film The Brothers Karamazov. He let the head of the studio, Benny Thau, and Abe Lastfogel, president of the William Morris Agency, decide the cast.[11] Richard Thorpe, who had the reputation of quickly finishing his projects, was chosen to direct the film.[20][21]

The first scene to be filmed was the title dance sequence to the song "Jailhouse Rock".[17] Alex Romero, who created moves inspired by Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, who incidentally was present at the wings when the first dress rehearsals for the scene were executed, tried his best to choreograph the sequence. Presley was not convinced by Romero's initial choreography, so on the next day Romero played some music and asked Presley to dance, using his own moves to choreograph the final sequence.[22] Impressed with the dance sequence, Kelly himself applauded the final product. It has been since confirmed by Russ Tamblyn that on the night prior to the shooting of the scene, he visited Presley at his penthouse suite at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in Beverly Hills. Although they had never met before, the one week older Tamblyn and Presley got along fine, immediately, then practiced a few moves and by the next morning, Presley had the complicated scene totally within his grasp, resulting in the scene often been cited as his greatest musical moment on screen.[23][24] [17] Brett Farmer, an expert in gay issues, places the "orgasmic gyrations" of the dance sequence within a lineage of cinematic musical numbers that offer a "spectacular eroticization, if not homoeroticization, of the male image";[25]

Shooting of the film began on May 13, 1957, with the newly created choreography.[26] Presley's characteristic hairstyle and sideburns were covered with a wig and makeup for the scenes in musical number and those set in the jail.[27] During the performance, one of Presley's dental caps fell out and became lodged in his lung. He was taken to the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, where he spent the night after the cap was removed.[17][26][27] Shooting was resumed the next day.[28] Throughout the film, Presley mimed the songs, which had been previously recorded in the studio and were added to the finished scenes.[29] Thorpe, who usually filmed scenes in a single take, finished the rest of the movie by June 17, 1957.[21][30][31] Jailhouse Rock was Judy Tyler's last film; two weeks after shooting was completed, she died in an automobile accident that also killed her husband.[32] Presley, moved by the death of his co-star, did not attend the film premiere.[33][nb 1]

Soundtrack

Before the production began, rock 'n' roll songwriting partners Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller were commissioned to create the film's soundtrack. The writers, who accepted the work, did not send any material to MGM for months. In April 1957, the studio called a meeting with the writers in New York City to be updated on the progress of the work. Leiber and Stoller, who had not written any material, traveled to New York where, instead of working, they toured the city. They were confronted in their hotel room by Jean Aberbach, director of Hill & Range music publishing company, who asked to see the songs. When he was told that there was no material, Aberbach decided to lock the songwriters in their hotel room by blocking the door with a sofa. Aberbach told them that they would not leave the room until they had created the material. Four hours later, Leiber and Stoller had written "I Want to Be Free", "Treat Me Nice", "(You're So Square) Baby I Don't Care", and "Jailhouse Rock".[34]

Presley recorded the finished songs at Radio Recorders in Hollywood on April 30 and May 3, 1957, with an additional session at the MGM soundstage in Hollywood on May 9 for "Don't Leave Me Now".[35] Leiber and Stoller were invited to the recording session of April 30, where they met Presley. During the session, Stoller helped Presley with the song "Treat Me Nice" and taught him, using a piano, the method he should use while recording the song. Presley was impressed by Stoller and convinced MGM to cast him as the band's pianist in the film.[16]

The following songs in the film were performed by Elvis unless otherwise noted:[36]

- "One More Day" (Sid Tepper, Roy C. Bennett) – performed by Mickey Shaughnessy

- "Young and Beautiful" (Abner Silver, Aaron Schroeder)

- "I Want to Be Free" (Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller)

- "Don't Leave Me Now" (Aaron Schroeder, Ben Weisman)

- "Treat Me Nice" (Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller)

- "Jailhouse Rock" (Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller) – dance routine was also choreographed by Elvis Presley

- "(You're So Square) Baby I Don't Care" (Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller) - Presley also played electric bass

Release

Jailhouse Rock premiered on October 17, 1957, at Loews State Theater in Memphis, Tennessee. It opened nationally on November 8.[32]

Box office

The film peaked at number 3 on the Variety box office chart, and reached number 14 for the year at the box office.[17][37]

According to MGM records the film earned $3.2 million in the US and Canada and $1,075,000 elsewhere during its initial theatrical run, resulting in a profit of $1,051,000.[1]

In 1957, Presley was ranked the fourth leading box office commodity in the film industry. According to Variety, by 1969, Jailhouse Rock's gross income in the United States and Canada was comparable to that of The Wizard of Oz (1939).[32]

Critical reception

Jailhouse Rock earned mixed reviews from critics. It was looked upon as scandalous once it was released because it portrayed Vince Everett as an anti-heroic character,[38][39] presented a convict as a hero, used the word "hell" as a profanity, and included a scene showing Presley in bed with co-star Tyler.[17] The Parent-Teacher Association described the movie as "a hackneyed, blown-up tale with cheap human values."[40] The New York Times criticized Guy Trosper for writing a screenplay where the secondary characters whom Mickey Shaughnessey and Judy Tyler acted out were "forced to hang on to the hero's flying mane and ego for the entire picture." Cue magazine called the film "[an] unpleasant, mediocre and tasteless drama."[41]

Some publications criticized Presley. Time criticized his onstage personality,[42] while The Miami News compared the film with horror movies, and said, "Only Elvis Presley and his 'Jailhouse Rock' can keep pace with the movie debut of this 'personality,' the records show. In estimating the lasting appeal of their grotesque performer."[43] Jazz magazine Down Beat said Presley's acting was "amateurish and bland."[44] British magazine The Spectator described Presley's evolution from his "silly" performance in Loving You to "dangerously near being repulsive."[45]

Other reviewers responded positively to the film. Louise Boyca of The Schenectady Gazette wrote that "it's dear Elvis that gets the soft focus camera and the arty photography." Boyca remarked upon the low production costs of the film, and said that Presley was "in top singing and personality form."[46] The Gadsden Times said, "Elvis Presley not only proves himself as a dramatic actor ... but also reveals his versatility by dancing on the screen for the first time. The movie ... also contains Elvis' unique style of singing."[47] Look favored the movie, describing the reception of an audience in a Los Angeles theater that "registered, loud and often, its approval of what may accurately be described as the star's first big dramatic singing role."[48]

Author Thomas Doherty wrote in his 2002 book Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenalization of American Movies in the 1950s: "In Jailhouse Rock, the treatment of rock 'n' roll music, both as narrative content and as cinematic performance is knowing and respectful ... The elaborate choreography for the title tune, the long takes and uninterrupted screen time given to the other numbers, and the musical pacing—the rock 'n' roll builds in quality and intensity—all show an indigenous appreciation of Presley's rock 'n' Roll."[49] Critic Hal Erickson of AllRovi wrote that the film "is a perfect balance of song and story from beginning to end".[50] Mark Deming, also a critic for AllRovi, wrote that Jailhouse Rock it was "one of [Presley's] few vehicles which really caught his raw, sexy energy and sneering charisma on film."[50]

The review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an overall 80% "Fresh" approval rating based on 15 reviews.[51]

Accolades

In 1991, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller were awarded with an ASCAP Award for Most Performed Feature Film Standards for the song "Jailhouse Rock".[52] In 2004, Jailhouse Rock was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, as it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[17] The film is famous for the dance sequence (also choreographed by Presley) in which Presley sings the title track while on stage, cavorting with other "inmates" through a set which resembles a block of jail cells. The sequence is widely acknowledged as the most memorable musical scene in Presley's 30 narrative movies, and is credited by music historians as the prototype for the modern music video.[31][53] Jailhouse Rock ranked 495th on Empire's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[54]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Jailhouse Rock" – #21[55]

- 2006: AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – Nominated[56]

Notes

- Some sources, such as Adam Victor in The Elvis Encyclopedia and Albert Goldman in Elvis, claim that Presley never watched the completed film.[17]

Footnotes

- The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Templeton & Craig 2002, pp. 15–6.

- Dundy 2004, pp. 286–87.

- Goldman 1981, p. 237.

- Cotten 1985, p. 129.

- Glut & Harmon 1975, p. 47.

- St. Joseph 1957.

- Garner & Mrotek 1999, p. 11.

- Dundy 2004, p. 286.

- TCM.

- Dickinson 2008, p. 63.

- Worth & Tamerius 1992, p. 229.

- Worth & Tamerius 1992, p. 230.

- Collins 2005, p. 88.

- Victor 2008, p. 269.

- Finler 2003, p. 151.

- Giglio 2010, p. 109.

- Eagan 2010, p. 536.

- Relyea 2008, p. 72.

- Humphries 2003, p. 52.

- Brown & Broeske 1997, p. 124.

- Poore 1998, p. 20.

- Farmer 2000, p. 86.

- Guralnick 1994, pp. 409–10.

- Slaughter 2005, p. 46.

- Relyea 2008, p. 71.

- Millard 2005, p. 239.

- Guralnick 1994, p. 413.

- Guralnick & Jorgensen 1999, p. 106.

- Templeton & Craig 2002, p. 16.

- Clayton 2006, p. 87.

- Collins 2005, pp. 84–7.

- Jorgensen 1998, pp. 89–90.

- Jorgensen 1998, pp. 90–2.

- Denisoff & Romanowski 1991, p. 87.

- Gabbard 1996, p. 125.

- Templeton & Craig 2002, p. 156.

- PTA 1957, p. 39.

- Cue 1958, p. 22.

- Dundy 2004, p. 290.

- Miami 1957, p. 73.

- Down Beat 1958, p. 21.

- The Spectator 1958, p. 107.

- Schenectady 1957, p. 25.

- Gadsden 1957, p. 3.

- Look 1957, p. 4.

- Doherty 2002, p. 77.

- AllRovi.

- Jailhouse Rock, Rotten Tomatoes

- The Hollywood Reporter 1991, p. 5.

- Browne-Cottrell 2008, p. 77.

- Empire 2008.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2016.

See also

References

- Books

- Brown, Peter Harry; Broeske, Pat H. (1997). Down at the End of Lonely Street: The Life and Death of Elvis Presley. New York City: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94246-7.

- Browne, Blaine; Cottrell, Robert (2008). Modern American Lives: Individuals and Issues in American History Since 1945. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-2223-5.

- Clayton, Marie (2006). Elvis Presley: Unseen Archives. Bath: Paragon Pub. ISBN 978-1-4054-0032-9.

- Collins, Ace (2005). Untold Gold: The Stories Behind Elvis's #1 Hits. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-565-0.

- Cotten, Lee (1985). All Shook Up: Elvis Day-by-Day, 1954–1977. Ann Arbor: Pierian Press. ISBN 978-0-87650-172-6.

- Denisoff, Serge; Romanowski, William (1991). Risky Business: Rock in Film. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-843-9.

- Dickinson, Kay (2008). Off Key: When Film and Music Won't Work Together. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532663-5.

- Doherty, Thomas (2002). Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-946-3.

- Dundy, Elaine (2004). Elvis and Gladys. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-634-6.

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York City: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-2977-3.

- Farmer, Brett (2000). Spectacular Passions: Cinema, Fantasy, Gay Male Spectatorships. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2589-5.

- Finler, Joel Waldo (2003). The Hollywood Story (3rd ed.). London: Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-903364-66-6.

- Gabbard, Krin (1996). Jammin' at the Margins: Jazz and the American Cinema. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-27788-2.

- Garner, Paul; Mrotek, Sharon (1999). Mousie Garner: Autobiography of a Vaudeville Stooge. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0581-7.

- Giglio, Ernest (2010). Here's Looking at You: Hollywood, Film & Politics. New York City: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0644-6.

- Glut, Donald F; Harmon, Jim (1975). The Great Television Heroes. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-05167-5.

- Goldman, Albert Harry (1981). Elvis. New York City: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-023657-8.

- Guralnick, Peter (1994). Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley. Boston: Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-33225-5.

- Guralnick, Peter; Jorgensen, Ernst (1999). Elvis: Day by Day: The Definitive Record of His Life and Music. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-42089-3.

- Humphries, Patrick (2003). Elvis the #1 Hits: The Secret History of the Classics. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7407-3803-6.

- Jorgensen, Ernst (1998). Elvis Presley A Life in Music: The Complete Recording Sessions. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-18572-5.

- Millard, Andre (2005). America on Record: A History of Recorded Sound (2nd ed.). New York City: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83515-2.

- Poore, Billy (1998). Rockabilly: A Forty-Year Journey. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corp. ISBN 978-0-7935-9142-8.

- Relyea, Robert; Relyea, Craig (2008). Not So Quiet On The Set: My Life in Movies During Hollywood's Macho Era. New York City: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-71332-5.

- Slaughter, Todd (2005). The Elvis Archives. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84609-067-7.

- Templeton, Steve; Craig, Yvonne (2002). Elvis Presley: Silver Screen Icon: A Collection of Movie Posters. Johnson City, Tennessee: The Overmountain Press. ISBN 978-1-57072-232-5.

- Victor, Adam (2008). The Elvis Encyclopedia. New York City: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3816-3.

- Worth, Fred; Tamerius, Steve (1992). Elvis: His Life From A to Z. New York City: Wings Books. ISBN 978-0-517-06634-8.

- Journals

- Boyka, Louise (November 28, 1957). "Elvis in 'Jailhouse Rock' Keeps Fans in Tears". Schenectady Gazette.

- Johnson, Erskine (November 3, 1957). "Hollywood Today!". Gadsden Times.

- Tynan, John (January 9, 1958). "Farewell, Elvis?". Down Beat. Maher Publications. 25 (1–6).

- "Monster' Films Get Big Play". The Miami News. December 8, 1957.

- "Young Judy Tyler Gives Her Formula for Broadway Success". The Sunday News Press. 79 (26). St. Joseph News-Press. February 25, 1956. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- "Movie Reviews". Cue: The Weekly Magazine of New York Life. Cue Publishing Co. February 8, 1958.

- "Jailhouse Rock – Movie Review". Look. Cowles Communications. 21 (14–26). September 17, 1957.

- "The Spectator". 200. Ian Gilmour. March 21, 1958. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The PTA magazine". 52. National Congress of Parents and Teachers. 1957. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Hollywood Reporter". 317 (1–18). Wilkerson Daily Corp. April 16, 1991. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Top Grosses of 1957". Variety. January 8, 1958.

- Other

- Erickson, Hal; Deming, Mark. "Jailhouse Rock – Synopsis/ Jailhouse Rock – Review". AllRovi. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Staff. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2012". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- "Jailhouse Rock (1957)". TCM. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Jailhouse Rock (1957)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jailhouse Rock (film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jailhouse Rock (film). |

- Jailhouse Rock essay by Carrie Rickey on the National Film Registry website

- Jailhouse Rock essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 535-536

- Jailhouse Rock on IMDb

- Jailhouse Rock at Rotten Tomatoes

- Jailhouse Rock at AllMovie

- Jailhouse Rock at the TCM Movie Database