Jacques Pelletier du Mans

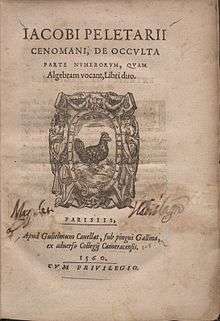

Jacques Pelletier du Mans, also spelled Peletier (Latin: Iacobus Peletarius Cenomani, 25 July 1517–17 July 1582) was a humanist, poet and mathematician of the French Renaissance.

Jacques Pelletier du Mans | |

|---|---|

| Born | 25 July 1517 |

| Died | 17 July 1582 Paris, France |

| Occupation | Humanist, Poet, Mathematician |

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Born in Le Mans into a bourgeois family, he studied at the Collège de Navarre in Paris, where his brother Jean was a professor of mathematics and philosophy. He subsequently studied law and medicine, frequented the literary circle around Marguerite de Navarre and from 1541 to 1543 he was secretary to René du Bellay. In 1541 he published the first French translation of Horace's Ars poetica and during this period he also published numerous scientific and mathematical treatises.

In 1547 he produced a funeral oration for Henry VIII of England and published his first poems (Œuvres poétiques), which included translations from the first two cantos of Homer's Odyssey and the first book of Virgil's Georgics, twelve Petrarchian sonnets, three Horacian odes and a Martial-like epigram; this poetry collection also included the first published poems of Joachim Du Bellay and Pierre de Ronsard (Ronsard would include Jacques Pelletier into his list of revolutionary contemporary poets La Pléiade). He then began to frequent a humanist circle around Théodore de Bèze, Jean Martin, Denis Sauvage.

In the Renaissance, the French language had acquired many inconsistencies in spelling through a misguided attempt to model French words on their Latin roots (see Middle French). Jacques Pelletier tried to reform French spelling in a 1550 treatise advocating a phonetic-based spelling using new typographic signs which he would continue to use in all his published works. In this system he consistently spells his name with one "l": Peletier.

Pelletier spent many years in Bordeaux, Poitiers, Piedmont (where he may have been the tutor of the son of Maréchal de Brissac), and Lyon (where he frequented the poets and humanists Maurice Scève, Louise Labé, Olivier de Magny and Pontus de Tyard). In 1555 he published a manual of poetic composition, Art poétique français, a Latin oration calling for peace from Henry II of France and emperor Charles V and a new collection of poetry, L'Amour des amours (consisting of a sonnet cycle and a series of encyclopedic poems describing meteors, planets and the heavens) which would influence poets Guillaume du Bartas and Jean-Antoine de Baïf.

His last years were spent in travels to the Savoy, Germany, Switzerland, possibly Italy, and various regions in France, and in publishing numerous works in Latin on algebra, geometry and mathematics, and medicine (including a refutation of Galen, and a work on the Plague). In 1572 he was briefly director of the College of Aquitaine in Bordeaux, but, bored by the position, he resigned. During this period he was friends with Michel de Montaigne and Pierre de Brach. In 1579 he returned to Paris and was named director of the College of Le Mans. A final collection of poetry Louanges was published in 1581.

Pelletier died in Paris in July or August 1582.

New naming convention for large numbers

While maintaining the original system of the French mathematician Nicolas Chuquet (1484) for the names of large numbers, Jacques Pelletier promoted milliard for 1012 which had been used earlier by Budaeus. In the late 17th century, milliard was subsequently reduced to 109. This convention is used widely in long scale countries.

|

| |||||

| Base 10 | Systematics | Chuquet | Peletier | SI Prefix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 0 | Million 0 | ||||

| 10 3 | Million 0.5 | ||||

| 10 6 | Million 1 | ||||

| 10 9 | Million 1.5 | ||||

| 10 12 | Million 2 | ||||

| 10 15 | Million 2.5 | ||||

| 10 18 | Million 3 | ||||

| 10 21 | Million 3.5 | ||||

| 10 24 | Million 4 | ||||

References

- (in French) Simonin, Michel, ed. Dictionnaire des lettres françaises - Le XVIe siècle. Paris: Fayard, 2001. ISBN 2-253-05663-4

- Revue Historique et Archéologique du Maine, Le Mans, 2000, passim.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacques Peletier du Mans. |

- English-language numerals

- French Renaissance literature

- Humanism

- Names of large numbers

- Nicolas Chuquet

- List of numbers

- Long and short scales