Italian cruiser Carlo Alberto

The Italian cruiser Carlo Alberto was the second of two Vettor Pisani-class armored cruisers built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) in the 1890s. She was deployed overseas several times during her career, notably to the Far East and South America. The ship was used as a royal yacht by King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy in 1902, during which time she was used for radio experiments by Guglielmo Marconi. Carlo Alberto served as a training ship before the start of the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–12. During the war she supported Italian operations in Libya. The ship was virtually inactive during World War I and was converted into a troop transport in 1917–18. Carlo Alberto was stricken from the Navy List in 1920 and subsequently broken up for scrap.

Carlo Alberto at anchor | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Carlo Alberto |

| Namesake: | Charles Albert of Sardinia |

| Builder: | Arsenale di La Spezia, La Spezia |

| Laid down: | 1 February 1892 |

| Launched: | 23 September 1896 |

| Completed: | 1 May 1898 |

| Renamed: | Zenson, 4 April 1918 |

| Reclassified: | Troop transport, 4 April 1918 |

| Stricken: | 12 June 1920 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement: | 6,397 t (6,296 long tons) |

| Length: | 105.7 m (346 ft 9 in) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 18.04 m (59 ft 2 in) |

| Draft: | 7.2 m (23 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 2 shafts, 2 vertical triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 5,400 nmi (10,000 km; 6,200 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 500–504 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

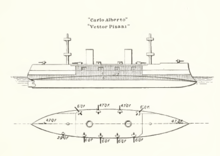

Design and description

Carlo Alberto had a length between perpendiculars of 99 meters (324 ft 10 in) and an overall length of 105.7 meters (346 ft 9 in). She had a beam of 18.04 meters (59 ft 2 in) and a draft of 7.2 meters (23 ft 7 in). The ship displaced 6,397 metric tons (6,296 long tons) at normal load, and 7,057 metric tons (6,946 long tons) at deep load.[1] The Vettor Pisani-class ships had a complement of 28 officers and 472 to 476 enlisted men.[2]

The ship was powered by two vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one propeller shaft. Steam for the engines was supplied by eight Scotch marine boilers. Designed for a maximum output of 13,000 indicated horsepower (9,700 kW) and a speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph),[3] Carlo Alberto barely exceeded her designed speed when she reached 19.1 knots (35.4 km/h; 22.0 mph) during her sea trials from 13,219 ihp (9,857 kW). She had a cruising radius of about 5,400 nautical miles (10,000 km; 6,200 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1]

The main armament of the Vettor Pisani-class ships consisted of twelve quick-firing (QF) Cannone da 152/40 A Modello 1891 guns in single mounts. All of these guns were mounted on the broadside, eight on the upper deck and four at the corners of the central citadel in armored casemates. Single QF Cannone da 120/40 A Modello 1891 guns were mounted in the bow and stern and the remaining two 120 mm (4.7 in) guns were positioned on the main deck between the 152 mm (6.0 in) guns. For defense against torpedo boats, the ship carried fourteen QF 57 mm (2.2 in) Hotchkiss guns and eight QF 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss guns. The ship was also equipped with four 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes.[2]

Carlo Alberto was protected by an armored belt that was 15 cm (5.9 in) thick amidships and reduced to 11 cm (4.3 in) at the bow and stern.[3] The upper strake of armor was also 15 cm thick and protected just the middle of the ship, up to the height of the upper deck. The curved armored deck was 3.7 cm thick. The conning tower armor was also 15 cm thick and each 15.2 cm gun was protected by a 5 cm (2.0 in) gun shield.[2]

Construction and career

Carlo Alberto, named after King Charles Albert of Sardinia,[4] was laid down on 1 February 1892 at the Arsenale di La Spezia in La Spezia.[2] The ship was launched on 23 September 1896 and completed on 1 May 1898.[1] She was deployed to South America later that year and returned to Italy on 28 February 1899. Later that year Carlo Alberto was sent to the Far East and returned on 1 June 1900.[5] After her return the ship was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet.[6]

Carlo Alberto served as the royal yacht for Victor Emmanuel III when he attended the Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom in 1902. Victor Emmanuel invited Guglielmo Marconi to accompany him and conduct radio experiments en route.[7] Originally scheduled for 26 June, the coronation was delayed by Edward's illness and rescheduled for 9 August. In the meantime, the ship took Victor Emmanuel to meetings with Tsar Nicholas II of Russia in Kronstadt. She returned to England before the coronation ceremony and then participated in the fleet review at Spithead on 16 August. On the return voyage Marconi conducted more long-range experiments with his site in Poldhu, Cornwall. The King then loaned Carlo Alberto to Marconi in September for more testing. She then ferried Marconi across the Atlantic to Glace Bay, Nova Scotia for further experiments transmitting radio messages across the ocean. After 15 December, when Marconi successfully transmitted messages from Glace Bay to Poldhu,[8] Carlo Alberto was sent to Venezuelan waters during the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–03, when an international force of British, German, and Italian warships blockaded Venezuela over the country's refusal to pay foreign debts.[9] She returned in early 1903 and was briefly deployed in Salonica later that year.[5] From 1907 to 1910 she served as a gunnery and torpedo training ship.[1]

When the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–12 began on 29 September, Carlo Alberto was assigned to the Training Division.[10] She bombarded the fortifications defending Tripoli and provided gunfire support to Italian forces at Zanzur, Zuara and elsewhere in Tripolitania. She fired enough ammunition during these missions that her guns had to be replaced in early 1912.[11] After the war the ship was transferred to the Aegean Sea where she remained until March 1913.[5]

Obsolescent by the beginning of World War I, Carlo Alberto was not very active during the war. She spent almost the entire war based in Venice.[5] The ship began conversion into a troop transport there in 1917. This required the removal of her armor, the addition of a new deck and internal modifications to suit her new role.[2] The work was finished in Taranto early the next year; she was recommissioned with the new name of Zenson on 4 April 1918. The ship was discarded on 12 June 1920 and subsequently scrapped.[2]

Notes

- Gardiner 1979, p. 350.

- Fraccaroli 1970, p. 28.

- Silverstone, p. 286

- Silverstone, p. 296

- Marchese

- Naval Notes–Italy

- Weightman, pp. 132–33

- Weightman, pp. 132–49

- Robinson, pp. 420–21

- Beehler, p. 10

- Stephenson, pp. 111–13, 117, 225; Beehler, pp. 65, 79, 84, 91

References

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0105-7.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Marchese, Giuseppe (February 1995). "La Posta Militare della Marina Italiana 5^ puntata". La Posta Militare (69). Archived from the original on 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- "Naval Notes–Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XLV (283): 1136. September 1901. OCLC 8007941.

- Robinson, Charles N., ed. (January 1903). "Navy and Army Illustrated". XV (310). London: Hudson & Kearns. OCLC 405497404. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Stephenson, Charles (2014). A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War 1911–1912: The First Land, Sea and Air War. Ticehurst, UK: Tattered Flag Press. ISBN 978-0-9576892-7-5.

- Weightman, Gavin (2003). Signor Marconi's Magic Box: The Most Remarkable Invention of the 19th Century & the Amateur Inventor Whose Genius Sparked a Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81275-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carlo Alberto. |