Iron Bowl

The Iron Bowl is the name given to the Alabama–Auburn football rivalry.[1] It is an American college football rivalry game between the Auburn University Tigers and University of Alabama Crimson Tide, both charter members of the Southeastern Conference (SEC). The series is considered one of the most important football rivalries in the annals of American sports.[2][3]

| |

| Sport | College football |

|---|---|

| First meeting | February 22, 1893 Auburn 32, Alabama 22 |

| Latest meeting | November 30, 2019 Auburn 48, Alabama 45 |

| Next meeting | November 28, 2020 |

| Trophy | James E. Foy, V-ODK Sportsmanship Trophy |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | 84 |

| All-time series | Alabama leads 46–37–1 (.554) |

| Largest victory | Alabama, 55–0 (1948) |

| Longest win streak | Alabama, 9 (1973–81) |

| Current win streak | Auburn, 1 (2019–present) |

|

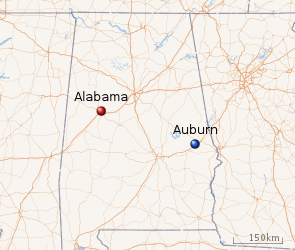

| Locations of Alabama and Auburn |

As the rivalry was played for many years at Legion Field in Birmingham, Alabama, the name of the Iron Bowl comes from Birmingham's historic role in the steel industry.[4] Auburn Coach Ralph "Shug" Jordan is credited with actually coining it—when asked by reporters in 1964 how he would deal with the disappointment of not taking his team to a bowl game, he responded, "We've got our bowl game. We have it every year. It's the Iron Bowl in Birmingham."[5]

Alabama has a winning record against all Southeastern Conference teams and leads the series with Auburn 46–37–1. The game is traditionally played on Thanksgiving weekend. In 1993, the schools agreed to move the game up to the week before Thanksgiving to give themselves a bye for a potential SEC Championship Game berth. In 2007 the conference voted to disallow any team from having a bye before the league championship game, returning the game to its traditional Thanksgiving weekend spot.

For much of the 20th century, the game was played every year in Birmingham, with Alabama winning 34 games and Auburn 19. Four games were played in Montgomery, Alabama, with each team winning two.[6] Since 2000, the games have been played at Jordan–Hare Stadium in Auburn every odd-numbered year and at Bryant–Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa every even-numbered year.

The rivalry has long been one of the most heated collegiate rivalries in the country. For many years, the two schools were the only Alabama colleges in what is now Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS). Together, they account for 33 SEC titles, 25 with Alabama and eight with Auburn. Both are among the winningest programs in major college football history; Alabama has won 17 national championships and is fifth all-time total wins among Division I FBS schools while Auburn is 13th with two national championships. The two schools have been fixtures on national television for the better part of the last four decades, and the season-ending clash has been nationally televised for all but one year since the late 1970s, the lone exception being 1993, when Auburn was barred from live TV due to NCAA sanctions.

Between them, one of the two teams played in the final five BCS National Championship Games, with Alabama winning in 2009, 2011, and 2012 and Auburn winning in 2010 and losing in 2013. Alabama has also made the four-team field of the successor to the BCS, the College Football Playoff, in each of its first five editions, losing in a semifinal in 2014, winning the title game in 2015 and 2017, and losing the title game in 2016 and 2018. Auburn has yet to participate in a playoff game.[n 1]

History

The contest became the extension of a bitter political debate which took place in the Alabama State Legislature regarding the location of the new land-grant college under the state's application under the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 during the Civil War Reconstruction Era. The state legislature, influenced by a heavy contingent of representatives who were University of Alabama alumni, pushed to sell the land scripts of 240,000 acres acquired from the Morrill Act or have any new land holdings held in conjunction with the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. The debate lasted over four years, until Lee County and the City of Auburn won the location of the new university in 1872, after donating more than a hundred acres and the remaining buildings and property of the East Alabama Male College.[7] At the time of the Auburn decision the state legislature and governorship was controlled by Radical Republicans such as "Scalawag" Southern Republicans and Freedman African-Americans. By 1874, former Confederate and "Redeemer" forces from the Democratic Party gradually overturned the Radicals' control of the legislature. The Democrats then attempted to overturn most legislation passed during the Reconstruction Period, including the founding of the new land-grant college at Auburn.

During the 1870s, Auburn (then named the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama) which received no appropriated funds from the state, was on the edge of financial collapse. Collapse of Auburn meant that the University of Alabama could assume the remaining land scripts, thus profiting from the closure of the new land-grant college. After its closure and burning during the Civil War, the University of Alabama would reopen in 1871 and in 1880 the U.S. Congress granted the university 40,000 acres (162 km²) of coal land in partial compensation for $250,000 in war damages.[8] "By 1877, competition between the University of Alabama and the Agricultural & Mechanical College for patronage had intensified. In January, Auburn President Isaac Tichenor, reported to the board of trustees that Alabama had reduced its tuition and lowered its graduation standards. Tichenor responded by requesting that the board drop tuition and create a boarding department to further lower expenses."[9]

Alabama and Auburn played their first football game in Lakeview Park in Birmingham, Alabama, on February 22, 1893. Auburn won 32–22, before an estimated crowd of 5,000. Alabama considered the game to be the final matchup of the 1892 season while Auburn recorded it as the first matchup of 1893.

In 1902, a bill was introduced into both houses of the U.S. Congress to fund the creation of a "School of Mines and Mining Engineering" at each land-grant college. Under the provision of the bill, each participating land-grant college would receive $5,000 annually with $500 each additional year for 10 years. The University of Alabama secretly sent Professor Dr. Eugene Smith to lobby against passage of the bill or to amend the bill to allow other universities to participate in the federal program. Auburn responded by sending Professor C.C. Thach to D.C. to lobby with the Association of Land-Grant Colleges for a compromise to allow passage of the bill. The bill would later fail to receive passage.[10]

During the 1907 state legislature session, a debate surfaced to move the land-grant college from Auburn to Birmingham.[11] Meanwhile, tensions carried over to the football rivalry when, after both the 1906 and 1907 contests, Auburn head coach Mike Donahue threatened to cancel the series if Alabama head coach "Doc" Pollard continued employing his elaborate formations and shifts.[12] The series was suspended after the 1907 game. The Alabama–Auburn series was originally thought to have been discontinued in response to violence both on the field and among fans during and after the 1907 game.[13] Other sources say the game was canceled due to a disagreement between the schools on how much per diem to allow players for the trip to Birmingham, how many players each school should bring, and where to find officials. By the time all these matters were resolved, it was too late to play in 1908.[13]

The first attempt to resume the series came only months after the 7–7 tie in 1907. The two schools, which ended the series because of a $34 dispute in the game contract, tried to save the series in 1908. In late September, Auburn agreed to accept a compromise contract as suggested by Alabama, and Alabama agreed to meet Auburn's demands on players and per diem. All that remained was the selection of a date. Auburn offered four possible dates to play. Before a reply was made, two of the dates passed and it was too late to change dates of other games. There were still two chances to play, including November 21 when Alabama had a game schedule with Haskell Institute, an Indian school, and November 28 (the Saturday after Thanksgiving that year). Alabama would not cancel the Haskell game, honoring its contract. That ruled out the 21st, and the Auburn Board of Trustees refused to change its long-standing rule prohibiting football games after Thanksgiving. The Auburn–Alabama series had stopped.[14]

During the 1930s and into the 1940s while the football rivalry was in hiatus, Auburn under the leadership of President Duncan, became the administrative home for several New Deal agencies: the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Resettlement Administration. The federal Government funding flowing into Auburn soon drew the ire of the University of Alabama trustees and their partisans in the Alabama Legislature. President Duncan was able to influence the placement of these agencies at Auburn due to his support for Governor Bibb Graves. Both the president and the governor supported the New Deal faction of the Democratic Party in Alabama. Graves was well connected in Washington D.C. with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and often lobbied in D.C. on "plum-tree-shaking expeditions". Meanwhile, Duncan with his connections in the Alabama Farm Bureau and as the director of the Extension Service exercised great control over the organized farm vote. By the mid 1940s, the Democratic Party was splintering in Alabama, with the rise of the Dixiecrats and those who remained loyal to the national party. One of the most out spoken critics of Auburn was publisher Harry Ayers, who would later endorse Harry Truman in 1945. In 1940 Duncan had successfully opposed Ayers' candidacy as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, which deeply offended the publisher. The Anniston editor had been a long-time advocate of consolidating Auburn and Alabama, "so that Auburn would become the dangling tail of a Tuscaloosa kite". In August, 1942, President Duncan wrote to Raymond Paty, the newly-appointed president of the University of Alabama, that the relationship between their two schools was "of such magnitude and gravity" that he had given the question more attention than any other problem he faced as president. He urged Paty that Auburn and Alabama should agree upon a funding formula that would give each institution the same appropriation per in-state student, an idea which worked against the University of Alabama's self-image as the state's capstone university.[15]

Auburn wanted to renew the football series in 1944. This time, Alabama said no. Alabama's Board of Trustees was against the resumption, saying that an Auburn–Alabama rivalry would lead to an overemphasis of football in Alabama and an unhealthy increase in rumor and rancor between the two schools. The Board also said an intrastate rivalry would make it impossible for either school to hire coaches of "high character and proven ability" because they would be afraid of beating the cross-state rival every year. After 1944, several legislative attempts were made to force the two schools to play again, but all attempts failed. The Legislature did, however, pass several resolutions calling on the two schools to play each other. Those resolutions were rejected by both schools.[14]

During a 1945 legislative session, the University of Alabama's report to the commission (Alabama Educational Survey Commission) argued that the Tuscaloosa school had well-established and broad responsibilities for higher education in the state. Four times in Alabama history, higher education responsibilities had been delegated to other institutions. In three of the four cases, this occurred under a state government established during the Reconstruction period: creation of the normal schools, higher education for blacks, and establishment of the land-grant college at Auburn. The fourth case was the state women's college at Montevallo. In each case, this was argued to have resulted from "the illogic inherent in the evolution of a democratic government". The Alabama report drew a sharp response from then Auburn President Luther Duncan, who said that he had never seen "a bolder, more deliberate, more vicious, or more deceptive document". He predicted that if the friends of Auburn and Montevallo did not rise up to combat "this evil monster", it would consume them "just like the doctrine of Hitler". Duncan also remarked that according to Alabama, "Auburn is the illegitimate children ... born out of the misery of the Reconstruction period."[15]

By 1945, with the end of World War II, the GI Bill had inundated Auburn (then officially named the Alabama Polytechnic Institute), with students—doubling enrollment twice between 1944 and 1948. With the increased enrollment, it was now obvious that Auburn would never "become so weak that ... it could be absorbed" by the University of Alabama.[15]

In March 1947, the Auburn Board of Trustees, with Governor Jim Folsom in attendance, unanimously approved the following resolution, "Whereas, The Alabama Polytechnic Institute and the University of Alabama are important educational institutions of the State of Alabama and are maintained and operated by the people of the State; and Whereas, many years ago athletic relationship between the Alabama Polytechnic Institute and the University of Alabama was discontinued; and Whereas, intercollegiate rivalry between the two institutions would be conducive to a better understanding among students of both schools and would tend to promote interest in athletic engagements in Alabama, therefore Be It Resolved by the Board of Trustees of Alabama Polytechnic Institute in meeting assembled, that the President of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, through its Athletic Director, make necessary negotiation with the Director of Athletics of the University of Alabama to resume athletic competition between the two institutions at the earliest possible date, and that a copy of this resolution be furnished to the President and Athletic Director of the University of Alabama." The Governor then suggested that the game be played not later than the first Saturday in December 1947.[16] Also during 1947, the Alabama House of Representatives passed a resolution encouraging both universities to "make possible the inauguration of a full athletic program between the two schools".[17] But the resolution did not have the effect of law, the schools still could not agree, the Legislature threatened to withhold state funding. In April 1948, Alabama president John Gallalee and Auburn president Ralph B. Draughon met and agreed to renew the series in 1948 and for the following 1949 season.[14]

It was agreed that the games would be played as a neutral site series in Birmingham. Legion Field held 47,000 fans in 1948, dwarfing both Tuscaloosa's Denny Stadium (31,000) and Auburn Stadium (15,000; expanded to 21,500 and renamed Cliff Hare Stadium in 1949).[18] Also it is believed Alabama refused to travel to Auburn, citing poor roads and the small size of Hare Stadium. Alabama was joined in this sentiment by the Tennessee Volunteers (who refused to play in Auburn until 1974 and Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets (who did not travel to Auburn from 1900 to 1970). Auburn played its last home game at Legion Field, outside of the Iron Bowl, in 1978 against Tennessee.[19][20]

Between 1969 and 1987, Auburn made additions to Jordan–Hare Stadium until it eclipsed Legion Field in size. Auburn was in the process of expanding Jordan-Hare Stadium from 72,169 seats to 85,214 for the 1987 season, so the old arguments that the on-campus facilities were not large enough for the Iron Bowl wouldn't hold up much longer. Legion Field by the mid-1980s had a capacity of 75,808. (Alabama's Bryant-Denny Stadium then seated a little over 60,000, but expanded to 70,123 in 1988.)[18] By this time, Auburn fans began feeling chagrin at playing all Iron Bowl games at Legion Field. Despite the equal allotment of tickets, Auburn fans insisted that Legion Field was not a neutral site. Not only was Legion Field just 45 minutes east of Tuscaloosa, but the stadium had long been associated with Alabama football. Well into the 1980s, Alabama played most of its important games in Birmingham—most of Alabama's "home" football history from the 1920s to the 1980s actually took place at Legion Field. For this reason, Auburn began lobbying to make the Iron Bowl a "home-and-home" series. Upon Pat Dye's hiring as Auburn head football coach and athletics director in 1981, Dye met with his longtime mentor, Alabama head coach and athletic director Bear Bryant. "When I saw Coach Bryant when I first got to Auburn, the first thing he said to me, very first thing, he said, 'Well, I guess you're going to want to take that game to Auburn,'" Dye recalled. "I said, 'We're going to take it to Auburn.' He said, 'Well, we've got a contract through 88.'{ ... I said, 'Well, we'll play 89 in Auburn.'" Dye knew he had legal grounds to move the Iron Bowl to Auburn, based on the language in the contractual agreement between the two schools, but he was smart enough to not bring it up while Bryant was still alive, let alone still coaching.[18]

In the late 80s, the schools agreed that Auburn could play their home games for the Iron Bowl at Jordan-Hare starting in 1989 (with the exception of 1991) and Alabama would continue to play its "home" games at Legion Field. On December 2, 1989, Alabama came to "the Plains" for the first time ever as a sellout crowd witnessed Auburn win its first true "home" game of the series, 30–20 over an Alabama team that entered the game undefeated and ranked No. 2 in the country.

Alabama continued to hold its home games for the rivalry at Legion Field. In 1998, Alabama expanded Bryant–Denny Stadium to a capacity of 83,818, narrowly eclipsing Legion Field. Alabama moved their home games in the series to Bryant–Denny Stadium in 2000. That year, Auburn came to Tuscaloosa for the first time since 1901 and won in a defensive struggle, 9–0. A new attendance record for the Iron Bowl was set in 2006 as the latest expansion to Bryant–Denny Stadium increased its capacity to 92,138. The record was reset again in 2010, after another expansion to Alabama's Bryant–Denny Stadium, when a crowd of 101,821 witnessed a 28–27 Auburn victory.

Broadcasters

In 2009 and 2010 CBS Sports and the two universities arranged to have the game played in an exclusive time slot on the Friday following Thanksgiving. The 2009 game was the sixth Iron Bowl to be played on a Friday and the first one in 21 years.[21] CBS did not attempt to renew the agreement after 2010 due to criticism from both fan bases, returning the game to its traditional Saturday date. Although CBS has broadcast the majority of Iron Bowl games since 1996 through its SEC coverage, ESPN has aired the game several times, from 1995 through 1999, 2003, and 2007. In 2014, CBS's decision to broadcast the Egg Bowl due to a number of factors (which included contractual limits on how many times CBS may feature certain teams, and the larger prominence of the Egg Bowl due to its potential effects on Mississippi State's participation in the College Football Playoff) resulted in ESPN broadcasting the first Iron Bowl played in primetime since 2007.[22][23]

Foy–ODK Trophy

The Foy–ODK Trophy is named after James E. Foy, a former dean of students at Auburn, and Omicron Delta Kappa, an honor society on both campuses since the 1920s. It is presented at halftime of the Alabama–Auburn basketball game later in the same academic year at the winner's home court, where the SGA President of the losing football team traditionally sings the winning team's fight song.

Notable games and moments

February 22, 1893: This was the first meeting between Auburn and Alabama. Auburn beat Alabama in Birmingham 32–22.

1904: On November 12, Mike Donahue defeated Alabama, the purpose for his hiring.[24]

1906: Alabama's star running back Auxford Burks scored all the game's points in a 10–0 victory. Auburn contended that Alabama player T. S. Sims was an illegal player, but the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA) denied the claim. Alabama coach Doc Pollard used a "military shift" never before seen in the south to gain an advantage over Auburn.[25]

1948: The rivalry resumed after being suspended for 41 years due to issues related to player per diems and officiating. Alabama beat Auburn 55–0 at Legion Field, which remains the largest margin of victory in series history.[26]

1964: In the first Iron Bowl broadcast on national television,[27] quarterback Joe Namath led Alabama to a 21–14 victory over Auburn.

1967: This was the first night game in the series. Thunderstorms soaked Legion Field, making the field extremely muddy. The game was frequently stopped to clear raincoats and other wet weather gear from the field. Late in the game, Alabama quarterback Ken Stabler ran 47 yards for a touchdown to give Alabama a 7–3 victory. This run became known in Alabama lore as the "run in the mud".

1972: Down 16–3 late in the game, Auburn blocked two punts and returned both for touchdowns, leading to an improbable 17–16 Auburn win and the coining of a new phrase among Auburn fans, "Punt Bama Punt!" In August 2010, ESPN.com ranked this game the 8th most painful outcome in college football history.[28]

1981: Alabama coach Bear Bryant earned his 315th career victory after Alabama defeated Auburn 28–17. With the victory, Coach Bryant passed Amos Alonzo Stagg to become the all-time winningest FBS coach at the time. This was the final game in Alabama's nine-game winning streak over Auburn, the longest one in Iron Bowl history.

1982: With two minutes left, Auburn drove the length of the field and scored a touchdown when running back Bo Jackson jumped over the top of the defensive line. Auburn won 23–22. The victory ended Alabama's nine-game winning streak over Auburn. This was the last Iron Bowl coached by Bear Bryant, who retired after the season and then died 60 days after the Auburn game.

1984: Trailing 17–15 late in the game, Auburn had 4th-and-goal from the one-yard line. Opting to go for it, Auburn called a pitch to running back Brent Fullwood. Running back Bo Jackson, who was supposed to block for Fullwood, ran the wrong direction, allowing the Alabama defense to easily force Fullwood out of bounds to seal the victory.[29][30]

1985: Alabama beat Auburn 25–23 on a 52-yard field goal by kicker Van Tiffin as time expired.[31][32]

1989: In the first Iron Bowl played at Jordan–Hare Stadium, Auburn defeated Alabama 30–20.

1993: No. 6 Auburn defeated No. 11 Alabama 22–14. The game, at Jordan Hare Stadium, was not televised due to Auburn's probation but was shown on closed-circuit television before 47,421 fans at Bryant–Denny Stadium.

1997: Trailing 17–15 late in the fourth quarter, Auburn recovered an Alabama fumble, setting up a 39-yard field goal with 20 seconds left. Auburn made it and won 18–17.

1999: Alabama beat Auburn 28–17, giving the Crimson Tide its first victory at Jordan–Hare Stadium.

2000: In the first game played in Bryant–Denny Stadium and the first game played in Tuscaloosa since 1901, Auburn kicked three field goals to beat Alabama 9–0.

2005: In a 28-18 Auburn victory, Alabama quarterback Brodie Croyle was sacked 11 times, an Iron Bowl record.

2007: Alabama head coach Nick Saban began his record in the Iron Bowl with a 17–10 loss at Auburn. It was the final game in Auburn's six-game Iron Bowl winning streak, their longest one over Alabama.

2008: Alabama defeated Auburn in Tuscaloosa for the first time in series history, 36–0, in Tommy Tuberville's last game as Auburn's head coach.

2009: Greg McElroy threw a four-yard touchdown pass to fullback Roy Upchurch with 1:24 remaining to lift No. 2 Alabama to a 26–21 win over Auburn at Jordan–Hare Stadium. That play capped a 15-play, 79-yard drive that consumed seven minutes and three seconds.

2010: No. 2 Auburn defeated No. 11 Alabama 28–27 in Tuscaloosa after erasing a 24–0 deficit—the largest comeback win in series history.

2013: With one second remaining and the game tied 28–28, Alabama's freshman kicker Adam Griffith attempted a 57-yard potential game-winning field goal. The kick fell short, and Auburn cornerback Chris Davis caught the ball at the back of the endzone and returned it 109 yards for a game-winning touchdown in what famously became known as the "Kick Six" game.[33][34] The 2013 Iron Bowl won the ESPY Award for "Best Game" of the year in any sport, and the final play by Davis won the ESPY Award for "Best Play" of the year.

2014: No. 1 Alabama defeated No. 15 Auburn 55–44, the highest scoring Iron Bowl ever.

2017: No. 6 Auburn defeated No. 1 Alabama, 26–14, their largest margin of victory over Alabama since 1969. Even though Alabama did not win the Western Division or SEC Conference title, the loss did not ultimately prevent Alabama from winning the 2017 national championship, marking the first time that either school went on to win a national championship after losing the Iron Bowl.

2019: No. 15 Auburn defeated No. 5 Alabama, 48–45, in a classic back-and-forth match. Late in the game, Alabama missed a field goal that "doinked" off the upright that would have tied the game. On the next possession, Auburn faced 4th down with more than one minute on the clock. Auburn's punter lined up as a wide receiver. Alabama was confused by the formation and received a penalty for having too many players on the field. The result gave Auburn a new set of downs and the ability to end the game by running out the remaining time. With the loss, Alabama was knocked out of playoff contention for the first time since the creation of the Playoff in 2014. This loss also marked the first time Alabama had two or more regular-season losses since 2010.

Game results

Since 1893, the Crimson Tide and Tigers have played 84 times. Alabama leads the series 46–37–1. The game has been played in four cities: Auburn, Birmingham, Montgomery, and Tuscaloosa. Alabama leads the series in Birmingham (34–18–1). Auburn leads the series in Tuscaloosa (7–5) and Auburn (10–5). The series is tied in Montgomery (2–2). Alabama leads the series since it was resumed in the modern era in 1948 (42–30). Interestingly, as of 2020, the series is tied 18-18 since the retirement of Coach Bear Bryant. For the first time in the series history, five consecutive Iron Bowl winners went to the BCS National Championship Game: Alabama in 2009,[35] Auburn in 2010,[36] and Alabama again in 2011[37] and 2012. Auburn also went in 2013, but lost to Florida State. Alabama's 2009 BCS National Championship followed by Auburn's 2010 BCS National Championship marks the first time that two different teams from the same state won consecutive BCS National Championships.

| Alabama victories | Auburn victories | Tie games |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Series record sources: 2011 Alabama Football Media Guide,[38] 2011 Auburn Football Media Guide,[39] and College Football Data Warehouse.[40]

References

Informational notes

- The years mentioned in this passage are college football seasons. Under both the BCS and CFP systems, the championship game is held in January of the calendar year following the season.

Citations

- "Why is Alabama vs. Auburn called the Iron Bowl?".

- "The ten greatest rivalries". ESPN. January 3, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- Rappoport, Ken; Barry Wilner (2007). "The Iron Bowl: Auburn–Alabama". Football Feuds: The Greatest College Football Rivalries. Globe Pequot. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-59921-014-8.

- Hyland, Tim. "Alabama–Auburn Rivalry—The Iron Bowl". About.com. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- "Iron Bowl 1964 was the first nationally televised, possibly the first called Iron Bowl".

- Staff (2016) "The Iron Bowl—wins and losses through the years" WSFA website

- "The Old South, Civil War, and Reconstruction". oldsouth.com. Auburn Education. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- Wolf, Suzanne Rau. The University of Alabama: A Pictorial History. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0119-4.

- "The New South". oldsouth.com. Auburn Education. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- "1902 Board Minutes of Alabama Polytechnic University". Auburn University Digital Library. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- "Auburn University Digital Library". diglib.auburn.edu.

- Groom, 2000, p. 16.

- Norman, Geoffrey (1986). Alabama Showdown. Kensington Publishing Company. pp. 48–50. ISBN 0-8217-2157-7.

- https://www.al.com/ironbowl/2010/11/iron_bowl_history_the_missing.html

- "Auburn University Digital Library". diglib.auburn.edu.

- http://content.lib.auburn.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/bot/id/8950/rec/111

- "The Auburn–Alabama Rivalry, "The Iron Bowl"". Rocky Mountain Auburn Club. 2006. Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- https://www.al.com/sports/2019/11/well-play-89-in-auburn-how-pat-dye-helped-break-birminghams-40-year-iron-bowl-stranglehold.html

- "UA Football Facts—Week 10, 2000". November 19, 2008. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008.

- "This is Alabama Football: Iron Bowl" (PDF). University of Alabama Athletics. p. 157. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- "Iron Bowl moves to Friday Rivalry game falls on day after Thanksgiving". Fox Sports. Archived from the original on August 10, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- "How ESPN landed the Iron Bowl, plus more Media Circus". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Paul Finebaum hears 'train wreck' predictions for live Iron Bowl show, phones ready this time". AL.com. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- A History of Southern Football by Fuzzy Woodruff, Volume 1, page 167

- Walsh, Christopher (September 15, 2016). "100 Things Crimson Tide Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die". Triumph Books – via Google Books.

- Little, Tom (December 5, 1948). [history.https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=cOk-AAAAIBAJ&sjid=Mk0MAAAAIBAJ&pg=6252%2C5186545 "Tide Whitewashes Auburn, 55–0"]. The Tuscaloosa News. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Lemke, Tim (November 27, 2009). "First Down: Best Auburn–Alabama games". The Washington Times. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- "College Football: House of Pain—ESPN". ESPN.com.

- "Upsets do happen". Press-Register. November 26, 2008. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Lowry, Will (December 2, 1984). "Dye defends decision to go for TD". The Tuscaloosa News. p. 13B. Retrieved November 27, 2011..

- Goens, Mike (December 2, 1985). "Tiffin—It was like a dream". TimesDaily. p. 1B. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Green, Lionel (November 24, 2010). "Crossville native Mike Bobo recalls 'The Kick' in 1985". Sand Mountain Reporter. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- "Auburn stuns Alabama with 109-yard field-goal return to end it:Play by Play". ESPN. ESPN. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- "Auburn stuns Alabama with 109-yard field-goal return to end it". ESPN. ESPN. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- Whiteside, Kelly (January 7, 2010). "Alabama sidesteps Texas' charge to emerge with BCS title". USA Today. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- "Auburn claims SEC's fifth straight national title by dropping Oregon on late field goal". Associated Press. ESPN. January 10, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Dufresne, Chris (January 9, 2012). "Alabama wins BCS title by dominating rematch with LSU". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- 2011 Alabama Football Media Guide Archived July 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, University of Alabama Department of Intercollegiate Athletics, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, pp. 176–195 (2011). Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- 2011 Auburn Tigers Football Media Guide, Auburn University Athletic Department, Auburn, Alabama, pp. 178–189, 191 (2011). Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- College Football Data Warehouse, Alabama vs Auburn Archived October 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Lars, "Alabama: State Of The Rivalry—Auburn's national title stirred no Crimson pride in neighboring Tuscaloosa", Sports Illustrated (January 24, 2011).

- Groom, Winston. The Crimson Tide—An Illustrated History. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8173-1051-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iron Bowl. |