Iraqi invasion of Iran

The Iraqi Invasion of Iran was launched on 22 September and lasted until 7 December 1980. The invasion stalled in the face of Iranian resistance, but not before Iraq captured more than 15,000 km2 of Iran's territory. This invasion led to eight years of war between Iran and Iraq.

| Iraqi invasion of Iran | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Iran–Iraq War | |||||||||

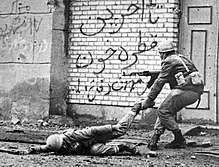

Iranian resistance during the Battle of Khorramshahr. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

(1st President of Iran and Commander-in-Chief) Mostafa Chamran † (Minister of Defence) Valiollah Fallahi (Joint chief of military staff) Qasem-Ali Zahirnejad (Joint chief of military staff) Mohsen Rezaee (Revolutionary Guards Commander) |

(President of Iraq) Ali Hassan al-Majid (General and Iraqi Intelligence Service head) Taha Yassin Ramadan (General and Deputy Party Secretary) Adnan Khairallah (Minister of Defence) Saddam Kamel (Republican Guard Commander) | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Iranian Armed Forces

| National Defense Battalions | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

At the onset of the war:[1] 110,000–150,000 soldiers, 1,700–2,100 tanks,[2] (500 operable)[3] 1,000 armoured vehicles, 300 operable artillery pieces,[4] 485 fighter-bombers (205 fully operational)[5], 750 helicopters |

At the onset of the war:[6] 200,000 soldiers, 2,800 tanks, 4,000 APCs, 1,400 artillery pieces, 380 fighter-bombers, 350 helicopters | ||||||||

After President of Iran Abolhassan Banisadr declared Iran was not following the 1975 Algiers Agreement and neither had Shah Pahlavi, on 17 September Iraqi President Saddam Hussein announced that Iraq abrogated the 1975 Algiers Agreement and intended to exercise full sovereignty over the disputed Shatt al-Arab river in response to Iranian violations of the treaty.[7] On 22 September, Iraqi aircraft bombarded ten airfields in Iran to cripple the Iranian air force on the ground. Although this attack failed, the next day Iraqi forces crossed the border in strength and advanced into Iran in three simultaneous thrusts along a front of some 400 miles (644 km). Of Iraq's six divisions that were invading by ground, four were sent to Khuzestan Province, which was located near the border's southern end, to cut off the Shatt al-Arab[note 1] from the rest of Iran and to establish a territorial security zone.[8]

The invasion's purpose, according to Saddam, was to blunt the edge of Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini's movement and thwart his attempts to export Iran's Islamic Revolution to Iraq and the Persian Gulf states.[9] It is claimed that Saddam hoped that by annexing Khuzestan, he would send such a blow to Iran's prestige that it would lead to the new government's downfall, or, at the very least, end Iran's calls for his overthrow.[10] However, the claim of hoping to annex Khuzestan is contradicted by Saddam calling for a renewed diplomacy and successive ceasefire offers, one of which came in the first two weeks of the war, which Ayatollah Khomeini refused.[11] He also wanted to elaborate his standing in the Arab world and among Arab countries.[12] Saddam expected the local Arabs of Khuzestan to rise against the Islamic government.[13] However, these objectives failed to materialize, and the majority of local Iranian Arabs fought alongside Iranian forces.

Iraq's purpose

Saddam's primary interest in war may have stemmed from his desire to right the supposed "wrong" of the Algiers Agreement, in addition to finally achieving his desire of annexing Khuzestan and becoming the regional superpower.[14] Saddam's goal was to replace Egypt as the "leader of the Arab world" and to achieve hegemony over the Persian Gulf.[15] He saw Iran's increased weakness due to revolution, sanctions, and international isolation.[16] Saddam had invested heavily in Iraq's military since his defeat against Iran in 1975, buying large amounts of weaponry from the Soviet Union and France. By 1980, Iraq possessed 200,000 soldiers, 2,000 tanks and 450 aircraft.[17]:1 Watching the powerful Iranian army that frustrated him in 1974–1975 disintegrate, he saw an opportunity to attack, using the threat of Islamic Revolution as a pretext.[17][18]

A successful invasion of Iran would enlarge Iraq's petroleum reserves and make Iraq the region's dominant power. With Iran engulfed in chaos, an opportunity for Iraq to annex the oil-rich Khuzestan Province materialized.[19]:261 In addition, Khuzestan's large ethnic Arab population would allow Saddam to pose as a liberator for Arabs from Persian rule.[19]:260 Fellow Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait (despite being hostile to Iraq) encouraged Iraq to attack, as they feared that an Islamic revolution would take place within their own borders. Certain Iranian exiles also helped convince Saddam that if he invaded, the fledgling Islamic republic would quickly collapse.[14] In 1979–80, Iraq was the beneficiary of an oil boom that saw it take in $33 billion, which allowed the government to go on a spending spree on civilian and military projects.[10] On several occasions, Saddam alluded to the Islamic conquest of Iran in promoting his position against Iran.[20][21]

In 1979–1980, anti-Ba'ath riots arose in the Iraq's Shia areas by groups who were working toward an Islamic revolution in their country.[10] Saddam and his deputies believed that the riots had been inspired by the Iranian Revolution and instigated by Iran's government.[14] On 8 March 1980, Iran announced it was withdrawing its ambassador from Iraq, downgraded its diplomatic ties to the charge d'affaires level, and demanded that Iraq do the same.[10][9] The following day, Iraq declared Iran's ambassador persona non-grata, and demanded his withdrawal from Iraq by 15 March.[22]

Iraq soon after expropriated the properties of 70,000 civilians believed to be of Iranian origin and expelled them from its territory.[23] Many, if not most, of those expelled were in fact Arabic-speaking Iraqi Shias who had little to no family ties with Iran.[24] This caused tensions between the two nations to increase further.[23]

In April 1980, Shia militants assassinated 20 Ba'ath officials, and Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz was almost assassinated on April 1.[10] Aziz survived, but 11 students were killed in the attack.[14] Three days later, the funeral procession being held to bury the students was bombed.[9] Iraqi Information Minister Latif Nusseif al-Jasim also barely survived an assassination attempt.[10] Shia dissidents' repeated calls for the overthrow of the Ba'ath party and the support they received from Iran's new government led Saddam to increasingly perceive Iran as a threat that, if ignored, might one day overthrow him.[10] He thus used the attacks as pretext for attacking Iran later that September,[9] though skirmishes along the Iran–Iraq border had already become a daily event by May that year.[10]

Iraq also helped to instigate riots among Iranian Arabs in Khuzestan province,[17] supporting them in their labor disputes,[17] and turning uprisings into armed battles between Iran's Revolutionary Guards and militants, killing over 100 on both sides. At times, Iraq also supported armed rebellion by the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran in Kurdistan, Iran's province.[25][26] The most notable of such events was the Iranian Embassy siege in London, in which six armed Khuzestani Arab insurgents took the Iranian Embassy's staff as hostages,[27][28] resulting in an armed siege that was finally ended by Britain's Special Air Service.

According to former Iraqi general Ra'ad al-Hamdani, the Iraqis believed that in addition to the Arab revolts, the Revolutionary Guards would be drawn out of Tehran, leading to a counter-revolution in Iran that would cause Khomeini's government to collapse and thus ensure Iraqi victory.[29] However, rather than turning against the revolutionary government as experts had predicted, Iran's people (including Iranian Arabs) rallied in support of the country and put up a stiff resistance.[14][17][30]

Prelude

In 1979–80, Iraq was the beneficiary of an oil boom that saw it take in US$33 billion, which allowed the government to go on a spending spree on both civilian and military projects.[10] On several occasions, Saddam alluded to the Islamic conquest of Iran in promoting his position against Iran. For example, on 2 April 1980, half a year before the war's outbreak, in a visit to Baghdad's al-Mustansiriya University, he drew parallels to Persia's defeat at the 7th century Battle of al-Qādisiyyah:

In your name, brothers, and on behalf of the Iraqis and Arabs everywhere we tell those Persian cowards and dwarfs who try to avenge al-Qadisiyah that the spirit of al-Qadisiyah as well as the blood and honor of the people of al-Qadisiyah who carried the message on their spearheads are greater than their attempts.[31][32][33]

In 1979–1980, anti-Ba'ath riots arose in the Iraq's Shia areas by groups who were working toward an Islamic revolution in their country.[10] Saddam and his deputies believed that the riots had been inspired by the Iranian Revolution and instigated by Iran's government.[14] On 10 March 1980, when Iraq declared Iran's ambassador persona non-grata, and demanded his withdrawal from Iraq by 15 March,[22] Iran replied by downgrading its diplomatic ties to the charge d'affaires level, and demanded that Iraq withdraw their ambassador from Iran. In April 1980, Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr and his sister Amina Haydar (better known as Bint al-Huda) were hanged as part of a crackdown to restore Saddam's control. The execution of Iraq's most senior Ayatollah caused outrage throughout the Islamic world, especially among Shias.[10]

In April 1980, Shia militants assassinated 20 Ba'ath officials, and Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz was almost assassinated on 1 April;[10] Aziz survived, but 11 students were killed in the attack.[14] Three days later, the funeral procession being held to bury the students was bombed.[9] Iraqi Information Minister Latif Nusseif al-Jasim also barely survived assassination by Shia militants.[10] The Shias' repeated calls for the overthrow of the Ba'ath party and the support they allegedly received from Iran's new government led Saddam to increasingly perceive Iran as a threat that, if ignored, might one day overthrow him;[10] he thus used the attacks as pretext for attacking Iran that September,[9] though skirmishes along the Iran–Iraq border had already become a daily event by May that year.[10]

Iraq soon after expropriated the properties of 70,000 civilians believed to be of Iranian origin and expelled them from its territory.[23] Many, if not most, of those expelled were in fact Arabic-speaking Iraqi Shias who had little to no family ties with Iran.[24] This caused tensions between the two nations to increase further.[23]

Iraq also helped to instigate riots among Iranian Arabs in Khuzestan province,[17] supporting them in their labor disputes,[17] and turning uprisings into armed battles between Iran's Revolutionary Guards and militants, killing over 100 on both sides. At times, Iraq also supported armed rebellion by the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran in Kurdistan.[25][26] The most notable of such events was the Iranian Embassy siege in London, in which six armed Khuzestani Arab insurgents took the Iranian Embassy's staff as hostages,[34][35] resulting in an armed siege that was finally ended by Britain's Special Air Service.

Border conflicts leading to war

By September, skirmishes between Iran and Iraq were increasing in number. Iraq began to grow bolder, both shelling and launching border incursions in disputed territories.[14] Malovany describes the Iraqi Army's seizure of the Zayn al-Qaws enclave, near Khanaqin (by 6th Armoured Division, 2nd Corps); the Saif Sa'ad enclave (10th Armoured Division) and the Maysan enclave between Shib and Fakkeh (1st Mechanised Division, 3rd Corps).[36] Iran responded by shelling several Iraqi border towns and posts, though this did little to alter the situation on the ground. By 10 September, Saddam declared that the Iraqi Army had "liberated" all disputed territories within Iran.[14] It should be carefully noted that Malovany, an ex-Israeli intelligence analyst writing years later, said the enclaves were not completely seized until 21 September.[37]

With the conclusion of the "liberating operations", on 17 September, in a statement addressed to Iraq's parliament, Saddam stated:

The frequent and blatant Iranian violations of Iraqi sovereignty...have rendered the 1975 Algiers Agreement null and void... This river [Shatt al-Arab]...must have its Iraqi-Arab identity restored as it was throughout history in name and in reality with all the disposal rights emanating from full sovereignty over the river...We in no way wish to launch war against Iran.[14]

Despite Saddam's claim that Iraq did not want war with Iran, the next day his forces proceeded to attack Iranian border posts in preparation for the planned invasion.[14] Iraq's 7th Mechanised and 4th Infantry Divisions attacked the Iranian border posts leading to the cities of Fakkeh and Bostan, opening the route for future armoured thrusts into Iran. Weakened by internal chaos, Iran was unable to repel the attacks; which in turn led to Iraq becoming more confident in its military edge over Iran and prompting them to believe in a quick victory.[14]

Operation

Air Attack

Iraq launched a full-scale invasion of Iran on 22 September 1980. The Iraqi Air Force launched surprise air strikes on ten Iranian airfields with the objective of destroying the Iranian Air Force,[10] mimicking Israeli Air Force in the Six-Day War. The attack failed to damage Iranian Air Force significantly: it damaged some of Iran's airbase infrastructure, but failed to destroy a significant number of aircraft: the Iraqi Air Force was only able to strike in depth with a few MiG-23BN, Tu-22, and Su-20 aircraft. Three MiG-23s managed to attack Tehran, striking its airport, but destroyed only a few aircraft.[38]

Ground Invasion

The next day, Iraq launched a ground invasion along a front measuring 644 km (400 mi) in three simultaneous attacks.[10]

Of Iraq's six divisions that were invading by ground, four were sent to Khuzestan, which was located near the border's southern end, to cut off the Shatt al-Arab[note 1] from the rest of Iran and to establish a territorial security zone.[10]:22 The other two divisions invaded across the northern and central part of the border to prevent an Iranian counter-attack.[10]

Northern Front

On the northern front, the Iraqis attempted to establish a strong defensive position opposite Sulaymaniyah to protect the Iraqi Kirkuk oil complex.[10]:23

Central Front

On the central front, the Iraqis occupied Mehran, advanced towards the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, and were able to block the traditional Tehran–Baghdad invasion route by securing territory forward of Qasr-e Shirin, Iran.[10]:23

Southern Front

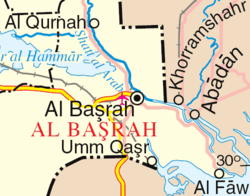

Two of the four Iraqi divisions which invaded Khuzestan, one mechanised and one armoured, operated near the southern end and began a siege of the strategically important port cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr.[10]:22 The other two divisions, both armoured, secured the territory bounded by the cities of Khorramshahr, Ahvaz, Susangerd, and Musian.[10]:22

Iraqi hopes of an uprising by the ethnic Arabs of Khuzestan failed to materialise, as most of the ethnic Arabs remained loyal to Iran.[10] The Iraqi troops advancing into Iran in 1980 were described by Patrick Brogan as "badly led and lacking in offensive spirit".[19]:261 The first known chemical weapons attack by Iraq on Iran probably took place during the fighting around Susangerd.[39]

First Battle of Khorramshahr

On 22 September, a prolonged battle began in the city of Khorramshahr, eventually leaving 7,000 dead on each side.[10] Reflecting the bloody nature of the struggle, Iranians came to call Khorramshahr "City of Blood" (خونین شهر, Khunin shahr).[10]

The battle began with Iraqi air raids against key points and mechanised divisions advancing on the city in a crescent-like formation. They were slowed by Iranian air attacks and Revolutionary Guard troops with recoilless rifles, rocket-propelled grenades, and Molotov cocktails.[40] The Iranians flooded the marsh areas around the city, forcing the Iraqis to traverse through narrow strips of land.[40] Iraqi tanks launched attacks with no infantry support, and many tanks were lost to Iranian anti-tank teams.[40] However, by 30 September, the Iraqis had managed to clear the Iranians from the outskirts of the city. The next day, the Iraqis launched infantry and armoured attacks into the city. After heavy house-to-house fighting, the Iraqis were repelled. On 14 October, the Iraqis launched a second offensive. The Iranians launched a controlled withdrawal from the city, street by street.[40] By 24 October, most of the city was captured, and the Iranians evacuated across the Karun River. Some partisans remained, and fighting continued until 10 November.

Iran's defense and counter attack

Though the Iraqi air invasion surprised the Iranians, the Iranian air force retaliated with an attack against Iraqi military bases and infrastructure in Operation Kaman 99 (Bow 99). Groups of F-4 Phantom and F-5 Tiger fighter jets attacked targets throughout Iraq, such as oil facilities, dams, petrochemical plants, and oil refineries, and included Mosul Airbase, Baghdad, and the Kirkuk oil refinery. Iraq was taken by surprise at the strength of the retaliation, as Iran took few losses while the Iraqis took heavy defeats and economic disruption.

The Iranian force of AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships began attacks on the advancing Iraqi divisions, along with F-4 Phantoms armed with Maverick missiles;[14] they destroyed numerous armoured vehicles and impeded the Iraqi advance, though not completely halting it.[41][42] Iran had discovered that a group of two or three low-flying F-4 Phantoms could hit targets almost anywhere in Iraq.[17]:1 Meanwhile, Iraqi air attacks on Iran were repulsed by Iran's F-14 Tomcat interceptor fighter jets, using Phoenix missiles, which downed a dozen of Iraq's Soviet-built fighters in the first two days of battle.[41]

_in_trench_during_Iran-Iraq_war.jpg)

The Iranian regular military, police forces, volunteer Basij, and Revolutionary Guards all conducted their operations separately; thus, the Iraqi invading forces did not face coordinated resistance.[10] However, on 24 September, the Iranian Navy attacked Basra, Iraq, destroying two oil terminals near the Iraqi port Faw, which reduced Iraq's ability to export oil.[10] The Iranian ground forces (primarily consisting of the Revolutionary Guard) retreated to the cities, where they set up defences against the invaders.[43]

On 30 September, Iran's air force launched Operation Scorch Sword, striking and badly damaging the Osirak nuclear reactor near Baghdad.[10]

By 1 October, Baghdad had been subjected to eight air attacks.[10]:29 In response, Iraq launched aerial strikes against Iranian targets.[10][41]

Iraqi advance stalls

The people of Iran, rather than turning against their still-weak Islamic Republic, rallied around their country. An estimated 200,000 fresh troops had arrived at the front by November, many of them ideologically committed volunteers.[30]

Though Khorramshahr was finally captured, the battle had delayed the Iraqis enough to allow the large-scale deployment of the Iranian military.[10] In November, Saddam ordered his forces to advance towards Dezful and Ahvaz, and lay sieges to both cities. However, the Iraqi offensive had been badly damaged by Iranian militias and air power. Iran's air force had destroyed Iraq's army supply depots and fuel supplies, and was strangling the country through an aerial siege.[41] On the other hand, Iran's supplies had not been exhausted, despite sanctions, and the military often cannibalised spare parts from other equipment and began searching for parts on the black market. On 28 November, Iran launched Operation Morvarid (Pearl), a combined air and sea attack which destroyed 80% of Iraq's navy and all of its radar sites in the southern portion of the country. When Iraq laid siege to Abadan and dug its troops in around the city, it was unable to blockade the port, which allowed Iran to resupply Abadan by sea.[44]

Iraq's strategic reserves had been depleted, and by now it lacked the power to go on any major offensives until nearly the end of the war.[10] On 7 December, Hussein announced that Iraq was going on the defensive.[10] By the end of 1980, Iraq had destroyed about 500 Western-built Iranian tanks and captured 100 others.[45][46]

See also

- Shatt al-Arab clashes

Notes

- Called Arvand Roud (اروندرود) in Iran and Shatt al-Arab(شط العرب) in Iraq

References

- Pollack, p, 186

- Farrokh, Kaveh, 305 (2011)

- Pollack, p. 187

- Farrokh, Kaveh, 304 (2011)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2018-11-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Pollack, p. 186

- David B. Ottaway (18 September 1980). "Iraq Cancels Border Pact With Iran". Washington Post.

- Karsh, Efraim (25 April 2002). The Iran–Iraq War: 1980–1988. Osprey Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-1841763712.

- Cruze, Gregory S. (Spring 1988). "Iran and Iraq: Perspectives in Conflict". Military Reports. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Karsh, Efraim (25 April 2002). The Iran–Iraq War: 1980–1988. Osprey Publishing. pp. 1–8, 12–16, 19–82. ISBN 978-1841763712.

- Loren Jenkins (5 October 1980). "Khomeini Rejects New Truce Offer, Calls for Victory". Washington Post.

- Murray, Williamson; Woods, Kevin M. (2014). The Iran-Iraq War: A Military and Strategic History. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 9781107062290.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-01-15. Retrieved 2015-12-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Farrokh, Kaveh. Iran at War: 1500–1988. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-221-4.

- "Britannica Online Encyclopedia: Saddam Hussein". Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Rajaee, Farhang, ed. (1993). The Iran-Iraq War: The Politics of Aggression. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813011776.

- "Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988". History of Iran. Iran Chamber Society. Archived from the original on 2010-01-15. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Fürtig, Henner (2012). "Den Spieß umgedreht: iranische Gegenoffensive im Ersten Golfkrieg" [Turning of the Tables: the Iranian counter-offensive during the first Gulf War]. Damals (in German). No. 5. pp. 10–13.

- Brogan, Patrick (1989). World Conflicts: A Comprehensive Guide to World Strife Since 1945. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-0260-9.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1981). Islam and Revolution: Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. Algar, Hamid. Mizan Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-933782-03-7.

- Mackey, Sandra; Harrop, W. Scott (1996). The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. Dutton. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-525-94005-0.

- "National Intelligence Daily" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 10 March 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Viewpoints of the Iranian political and military elites". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- Westcott, Kathryn (27 February 2003). "Iraq's rich mosaic of people". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- Noi, Aylin. "The Arab Spring, Its Effects on the Kurds". Archived from the original on 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- "Kurdistan, Iraq Global Security". Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- Coughlin, Con. "Lets Deport the Iran Embassy Siege survivor to Iraq". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2009). Who dares wins the SAS and the Iranian embassy siege, 1980. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-78096-468-3.

- Woods, Kevin. "Saddam's Generals: A Perspective of the Iran-Iraq War" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2013.

- Pike, John (ed.). "Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988)". Archived from the original on 2011-02-28. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Speech made by Saddam Hussein. Baghdad, Voice of the Masses in Arabic, 2 April 1980. FBIS-MEA-80-066. 3 April 1980, E2-3. E3

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1981). Islam and Revolution: Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. Algar, Hamid. Mizan Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0933782037.

- Mackey, Sandra; Harrop, W. Scott (1996). The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. Dutton. p. 317. ISBN 9780525940050.

- Coughlin, Con. "Lets Deport the Iran Embassy Siege survivor to Iraq". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2009). Who dares wins the SAS and the Iranian embassy siege, 1980. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 9781780964683.

- Malvany, Wars of Modern Babylon, 2017, 104-7.

- Malovany, 2017, 106.

- Cordesman, Anthony H.; Wagner, Abraham (1990). The Lessons of Modern War: Volume Two – The Iran-Iraq Conflict. Westview Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0813309552.

- Robinson, Julian Perry; Goldbat, Jozef (May 1984). "Chemical Warfare in the Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988". History of Iran. Iran Chamber Society. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Wilson, Ben (July–August 2007). "The Evolution of Iranian Warfighting During the Iran-Iraq War: When Dismounted Light Infantry Made the Difference" (PDF). U.S. Army: Foreign Military Studies Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cooper, Thomas; Bishop, Farzad (9 September 2003). "Persian Gulf War: Iraqi Invasion of Iran, September 1980". Arabian Peninsula and Persian Gulf Database. Air Combat Information Group. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Modern Warfare: Iran-Iraq War (film documentary).

- Wilson, Ben. "The Evolution of Iranian Warfighting during the Iran-Iraq War" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29.

- Aboul-Enein, Youssef; Bertrand, Andrew; Corley, Dorothy (12 April 2012). "Egyptian Field Marshal Abdul-Halim Abu Ghazalah on the Combat Tactics and Strategy of the Iran-Iraq War". Small Wars Journal. Ghazalah's Phased Analysis of Combat Operations. Small Wars Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Tucker, A. R. (1988). Armored warfare in the Gulf. Armed Forces, May, pp.226.

- "Irano-Irakskii konflikt. Istoricheskii ocherk." Niyazmatov. J.A. — M.: Nauka, 1989.