Invadopodia

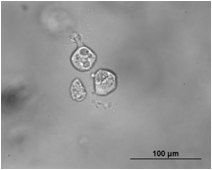

Invadopodia are actin-rich protrusions of the plasma membrane that are associated with degradation of the extracellular matrix in cancer invasiveness and metastasis.[1][2] Very similar to podosomes, invadopodia are found in invasive cancer cells and are important for their ability to invade through the extracellular matrix, especially in cancer cell extravasation.[3] Invadopodia are generally visualized by the holes they create in ECM (fibronectin, collagen etc.)-coated plates, in combination with immunohistochemistry for the invadopodia localizing proteins such as cortactin, actin, Tks5[1][2][4] etc. Invadopodia can also be used as a marker to quantify the invasiveness of cancer cell lines in vitro using a hyaluronic acid hydrogel assay.[5]

History and controversy

In the early 1980s, researchers noticed protrusions coming from the ventral membrane of cells that had been transformed by the Rous Sarcoma Virus and that they were at the sites of cell-to-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion.[1] They termed these structures podosomes, or cellular feet, but it was later noticed that degradation of the ECM was occurring at these sites and the name invadopodia was coined to highlight the invasive nature of these protrusions.[1] Since then, researchers have often used the two names interchangeably, but it is generally accepted that podosomes are the structures involved in normal biological processes (as when immune cells must cross tissue barriers or in bone remodeling[6]) and invadopodia are the structures in invading cancer cells.[1] However, there remains controversy around this nomenclature, with some scientists arguing that the two are different enough to be considered distinct structures while others argue that invadopodia are simply disregulated podosomes and cancer cells don’t simply "invent" new mechanisms. Due to this confusion and the high similarity between the two structures, many have begun to group the two under the collective term invadosomes.[3]

Structure and formation

Invadopodia have an actin core, which is surrounded by a ring structure enriched in actin-binding proteins, adhesion molecules, integrins, and scaffold proteins.[1][2][3][7] Invadopodia are generally longer than podosomes, with a width of 0.5- 2.0 um and a length greater than 2 um, and they last much longer than podosomes.[1] Invadopodia also penetrate deep into the ECM, while podosomes generally extend upward into the cytoplasm and do not cause as much ECM degradation.[3]

Invadopodia formation is a complex process that involves multiple signaling pathways and can be described as having three steps: initiation, stabilization, and maturation.[7][8] Initiation of invadopodia involves the formation of buds in the plasma membrane and is initiated by growth factors like epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which act through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) to activate Src family kinases.[1] These kinases have key roles in the formation of invadopodia and when activated, phosphorylate multiple proteins involved in invadopodia formation including Tks5, synaptjanin-2, and the Abl-family kinase Arg4. The phosphorylation of these proteins leads to the recruitment of the Neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-Wasp) to invadopodia, which requires Arp2/3, to activate actin polymerization and thus invadopodia elongation.[9] A key step during invadopodia formation is the stabilization of invadopodia, which involves the interaction of PX domain of Tks5 (a scaffold protein) with phospholipid, PI(3,4)P2 to anchor the invadopodia core to the plasma membrane.[7] Maturation of invadopodia requires sustained actin polymerization and there are several regulators of actin polymerization involved in this step, including cofilin, fascin, Arg kinase, and mDia2.[9] Invadopodia are considered mature when matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), specifically MMP2, 9, and 14, are recruited to the invadopodium to be released into the extracellular matrix.[9]

Role in cancer metastasis

Metastasis is the leading cause of mortality in cancer patients; it relies on the ability of cancer cells to degrade the surrounding extracellular matrix and invade other tissues. The mechanisms of this process are still not completely understood, and because of the invasive properties of invadopodia, they have been investigated in this context. Indeed, invadopodia have been implicated in many cancers and cancer cells. Increased invasiveness of cancer cells correlates with invadopodia presence, and cancer cells have been observed to project them into the endothelium of blood vessels during extravasation, an important step in metastasis.[10] Invadopodia have also been shown to correlate with a poorer prognosis in breast cancer patients.[11]

Tks5, a protein specific for invadopodia, has been implicated in cancer invasiveness. Increased levels of tks5 have been detected in prostate cancer and overexpression of Tks5 was sufficient to induce invadopodia formation and degradation of the extracellular matrix in an Src-dependent manner.[12] Increased Tks5 expression has been shown to correlate with poor patient prognosis in gliomas.[13] In a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma, invasive tumors were shown to have an increased expression of a long isoform of tks5 while non-metastatic tumors had a short isoform. It was also shown that overexpression of the long isoform of tks5 was sufficient to cause non-metastatic tumors to become invasive.[14]

Therapeutic relevance

Due to the invasive nature of invadopodia in cancer cells, research has focused on targeting invadopodia as a potential therapeutic target to inhibit metastasis. Inhibiting invadopodia formation by targeting Src kinase with Saracatanib in a chicken model system showed a decreased incidence of invadopodia and decreased cancer extravasation. In mice, inhibiting invadopodia formation directly, through RNAi against tks4 or tks5, significantly reduced cancer extravasation.[10] Screening for drug activators and inhibitors of invadopodia revealed that Cdc5 can be a target for inhibiting invadopodia formation and also that, paradoxically, paclitaxel, a drug commonly used to treat cancer, induces invadopodia formation.[15] These results show potential for invadopodia as a therapeutic target, and research in this field continues.

See also

References

- Murphy DA, Courtneidge SA (June 2011). "The 'ins' and 'outs' of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation and function". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (7): 413–26. doi:10.1038/nrm3141. PMC 3423958. PMID 21697900.

- Eddy RJ, Weidmann MD, Sharma VP, Condeelis JS (August 2017). "Tumor Cell Invadopodia: Invasive Protrusions that Orchestrate Metastasis". Trends in Cell Biology. 27 (8): 595–607. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2017.03.003. PMC 5524604. PMID 28412099.

- Seano G, Primo L (2015). "Podosomes and invadopodia: tools to breach vascular basement membrane". Cell Cycle. 14 (9): 1370–4. doi:10.1080/15384101.2015.1026523. PMC 4614630. PMID 25789660.

- Stylli SS, Stacey TT, Verhagen AM, Xu SS, Pass I, Courtneidge SA, Lock P (August 2009). "Nck adaptor proteins link Tks5 to invadopodia actin regulation and ECM degradation". Journal of Cell Science. 122 (Pt 15): 2727–40. doi:10.1242/jcs.046680. PMC 2909319. PMID 19596797.

- Gurski LA, Xu X, Labrada LN, Nguyen NT, Xiao L, van Golen KL, et al. (2009). "Hyaluronan (HA) interacting proteins RHAMM and hyaluronidase impact prostate cancer cell behavior and invadopodia formation in 3D HA-based hydrogels". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e50075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050075. PMC 3500332. PMID 23166824.

- Weaver AM (May 2008). "Invadopodia". Current Biology. 18 (9): R362-4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.028. PMID 18460310.

- Sharma VP, Eddy R, Entenberg D, Kai M, Gertler FB, Condeelis J (November 2013). "Tks5 and SHIP2 regulate invadopodium maturation, but not initiation, in breast carcinoma cells". Current Biology. 23 (21): 2079–89. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.044. PMC 3882144. PMID 24206842.

- Oser M, Yamaguchi H, Mader CC, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Arias M, Chen X, et al. (August 2009). "Cortactin regulates cofilin and N-WASp activities to control the stages of invadopodium assembly and maturation". The Journal of Cell Biology. 186 (4): 571–87. doi:10.1083/jcb.200812176. PMC 2733743. PMID 19704022.

- Jacob A, Prekeris R (February 2015). "The regulation of MMP targeting to invadopodia during cancer metastasis". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 3: 4. doi:10.3389/fcell.2015.00004. PMC 4313772. PMID 25699257.

- Leong HS, Robertson AE, Stoletov K, Leith SJ, Chin CA, Chien AE, et al. (September 2014). "Invadopodia are required for cancer cell extravasation and are a therapeutic target for metastasis". Cell Reports. 8 (5): 1558–70. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.050. PMID 25176655.

- Blouw B, Patel M, Iizuka S, Abdullah C, You WK, Huang X, et al. (2015). "The invadopodia scaffold protein Tks5 is required for the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0121003. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121003. PMC 4380437. PMID 25826475.

- Burger KL, Learman BS, Boucherle AK, Sirintrapun SJ, Isom S, Díaz B, et al. (February 2014). "Src-dependent Tks5 phosphorylation regulates invadopodia-associated invasion in prostate cancer cells". The Prostate. 74 (2): 134–48. doi:10.1002/pros.22735. PMC 4083496. PMID 24174371.

- Stylli SS, I ST, Kaye AH, Lock P (March 2012). "Prognostic significance of Tks5 expression in gliomas". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (3): 436–42. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2011.11.013. PMID 22249020.

- Li CM, Chen G, Dayton TL, Kim-Kiselak C, Hoersch S, Whittaker CA, et al. (July 2013). "Differential Tks5 isoform expression contributes to metastatic invasion of lung adenocarcinoma" (PDF). Genes & Development. 27 (14): 1557–67. doi:10.1101/gad.222745.113. PMC 3731545. PMID 23873940.

- Courtneidge SA (February 2012). "Cell migration and invasion in human disease: the Tks adaptor proteins". Biochemical Society Transactions. 40 (1): 129–32. doi:10.1042/BST20110685. PMC 3425387. PMID 22260678.