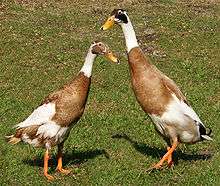

Indian Runner duck

Indian Runners are a breed of Anas platyrhynchos domesticus, the domestic duck. They stand erect like penguins and, rather than waddling, they run. The females usually lay about 300 to 350 eggs a year or more, depending whether they are from exhibition or utility strains. They were found on the Indonesian islands of Lombok, Java and Bali where they were 'walked' to market and sold as egg-layers or for meat. These ducks do not fly and only rarely form nests and incubate their own eggs. They run or walk, often dropping their eggs wherever they happen to be. Duck-breeders need to house their birds overnight or be vigilant in picking up the eggs to prevent them from being taken by other animals.

| |

| Traits | |

|---|---|

| Weight |

|

| Skin color | Pink |

| Egg color | Greenish blue |

| Comb type | None |

| Classification | |

| PCGB | light[1] |

| |

The ducks vary in weight between 1.4 and 2.3 kg (3.1 and 5.1 lb). Their height (from crown to tail tip) ranges from 50 cm (20 in) in small females to about 76 cm (30 in) in the taller males. The erect carriage is a result of a pelvic girdle that is situated more towards the tail region of the bird compared to other breeds of domestic duck.[2] This structural feature allows the birds to walk or "quickstep", rather than waddle, as seen with other duck breeds.[2][3] Indian Runner ducks have a long, wedge-shaped head.[3] The bill blends into the head smoothly being as straight as possible from bean to the back of the skull.[3] The head is shallower than what is seen with most other breeds of duck. This effect gives a racy appearance, a breed trait.[3] Eye placement is high on the head. Indian Runners have long, slender necks that smoothly transition into the body.[3] The body is long, slim but round in appearance.[3] The eggs are often greenish-white in color. Indian Runners have tight feathering. Drakes have a small curl on the tip of their tails, while hens have flat tails. It's difficult to determine their sex until they are fully mature.

They often swim in ponds and streams, but they are likely to be preoccupied foraging in grassy meadows for worms, slugs, even catching flies. They appreciate open spaces but are happy in gardens from which they cannot fly and where they make much less noise than call ducks. Only females quack and drakes are limited to a hoarse whisper. Compared to big table ducks, they eat less grain and pellet supplements.

Origins of the breed

The Indian Runner ducks are domesticated waterfowl that live in the archipelago of the East Indies. There is no evidence that they came originally from India itself. Attempts by British breeders at the beginning of the twentieth century to find examples in the subcontinent had very limited success. Like many other breeds of waterfowl imported into Europe and America, the term 'Indian' may well be fanciful, denoting a loading port or the transport by 'India-men' sailing ships of the East India Company. Other misnamed geese and ducks include the African goose, the black East Indian duck and the Muscovy duck.

The Runner became popular in Europe and America as an egg-laying variety towards the end of the nineteenth century largely as a result of an undated pamphlet called The India Runner: its History and Description published by John Donald of Wigton between 1885[4] and 1890.[5] Donald's publication is advertised briefly in The Feathered World, 1895, under the title of "The Indian Runner Duck". Donald describes the pied variety and gives the popular story of the importation into Cumbria (Northwest England) by a sea captain some fifty years earlier.

The breed is unusual not only for its high egg production but also for its upright stance and variety of color genes, some of which are seen in seventeenth century Dutch paintings.[6] Other references[7] to such domestic ducks use the names 'Penguin Ducks' and 'Baly Soldiers'. Harrison Weir's Our Poultry (1902) describes the Penguin Ducks belonging to Mr Edward Cross in the Surrey Zoological Gardens between 1837–38. These may well have been imported by the 13th Earl of Derby.[8] Darwin describes them (1868) as having elongated 'femur and meta-tarsi', contrary to Tegetmeier's assertions.[9]

The Cumbrian importations, according to Matthew Smith in 1923,[10] included completely fawn Runners and completely white Runners as well as the pied (fawn-and-white and grey-and-white) varieties. The most successful attempt to import fresh blood lines was by Joseph Walton between 1908 and 1909. Accounts of these ventures can be found in Coutts (1927) and Ashton (2002). Walton shipped in birds from Lombok and Java, revolutionizing the breeding stock which, according to Donald, had become badly mixed with local birds.[11] Further importations by Miss Chisholm and Miss Davidson in 1924 and 1926[12] continued to revive the breed.

Development

Pure breed enthusiasts, exhibitors and show judges wanted to establish standard descriptions. Standards were drawn up in by the Waterfowl Club in England (1897)[13] and America (1898) for the pied color varieties. These were largely the same until 1915 when the two countries diverged. The American Poultry Association chose a variety with blue in the genotype whilst the English Poultry Club Standard kept to the pure form described by Donald in his original pamphlet. Other colors followed making use of black genes brought in by some of Walton's birds. These were to produce black, chocolate and Cumberland blue. Later were developed the mallard, trout, blue trout, and apricot trout versions.[14] Slightly different names and descriptions can be found in American and German standards. An account of the influence of the Indian Runner Duck Club (founded in 1906), particularly the input by John Donald, Joseph Walton, Dr J. A. Coutts and Matthew Smith, can be found in Ashton (2002).

The most profound impact of the Indian Runners was on the development of the modern 'light duck' breeds. Before 1900, most ducks were bred for the table. Aylesbury and Rouen ducks were famous throughout the nineteenth century, and these were supplemented or replaced, after 1873–74, by importation from China of the Pekin duck. As soon as the Indian Runners became fashionable, a demand for egg-layers and general purpose breeds developed. Using Runners crossed to Rouens, Aylesburys and Cayugas (the large black American breed), William Cook produced his famous Orpington Ducks. Mrs Campbell crossed her fawn-and-white Runner duck to a Rouen drake to create the Campbell ducks introduced in 1898. Later, she introduced wild mallard blood and managed to create the most prolific egg-layer, the Khaki Campbell (announced in 1901). Other breeds followed, some of which emerged as direct mutations of the Khaki Campbell, along with crosses back to Indian Runners, the most famous being the Abacot Ranger (known in Germany as the Streicher) and the Welsh Harlequin. Currently there are eight varieties of Indian Runner recognized with the American Poultry Association. They are, in order of recognition, Fawn & White, White, Penciled, Black, Buff, Chocolate, Cumberland Blue, and Gray.[2][3]

Color breeding

Indian Runner ducks and Pekins brought in unusual plumage colour mutations. These included the dusky and restricted mallard genes, light phase, harlequin phase, blue and brown dilutions, as well as the famous pied varieties named by the geneticist F. M. Lancaster[15] as the 'Runner pattern'. Much of the proliferation of new colour varieties in breeds of domestic duck begins with the importation of these oriental ducks. Original research by R. G. Jaap (1930s) and F. M. Lancaster has allowed breeders to understand the effect of genotypes in managing and creating colour varieties. Simplified information can be found in writings by Dave Holderread, and Mike and Chris Ashton.[16]

See also

References

- Breed Classification. Poultry Club of Great Britain. Archived 12 June 2018.

- Holderread, Dave (2001). Storey's Guide to Raising Ducks. North Adams, MA, USA: Storey Publishing. pp. 47, 48, 49, 50.

- Standard Revision Committee; Malone, Pat; Donnelly, Gerald; Leonard, Walt (2001). American Standard of Perfection 2001. USA: American Poultry Association. pp. 314, 315.

- Edward Brown, Poultry Breeding and Production, Vol. 3, 1929

- J.A.Coutts, The Indian Runner Duck, 1927

- By the d’Hondecoeter family and others. See the Indian Runner Duck Association website: Archived 22 February 2013 at Archive.today

- By Darwin (1868), Zollinger (Journal of the Indian Archipelago, 1851) and Wallace (The Malay Archipelago, 1856 note)

- By Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Rudolph, Indian Runner Duck Association Year Book

- Tegetmeier, The Poultry Book (1867), which emphasizes the 'extreme shortness of the femora'.

- In Coutts (1927)

- John Donald, The India Runner: its History and Description (1885–90): 'very few of the original type are now to be found.

- See Ashton (2002) pp.105–122.

- Digby, Henry. How to make £50 a Year by Keeping Ducks. 1897.

- Detailed descriptions of these are to be found in British Waterfowl Standards (BWA 2008).

- F. M. Lancaster, The inheritance of plumage colour in the common duck (1963), and mutations and major variants in domestic ducks in Poultry Breeding and Genetics edited by R. D. Crawford (1990)

- Storey’s Guide to Raising Ducks (Holderread, 2001); The Domestic Duck (2001) and Colour Breeding in Domestic Ducks (2007) (C. and M. Ashton)

![]()