Imagism

Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language. It has been described as the most influential movement in English poetry since the Pre-Raphaelites.[1] As a poetic style it gave modernism its start in the early 20th century,[2] and is considered to be the first organized modernist literary movement in the English language.[3] Imagism is sometimes viewed as "a succession of creative moments" rather than a continuous or sustained period of development.[2] René Taupin remarked that "it is more accurate to consider Imagism not as a doctrine, nor even as a poetic school, but as the association of a few poets who were for a certain time in agreement on a small number of important principles".[4]

The Imagists rejected the sentiment and discursiveness typical of much Romantic and Victorian poetry, in contrast to their contemporaries, the Georgian poets, who were generally content to work within that tradition. Imagism called for a return to what were seen as more Classical values, such as directness of presentation and economy of language, and a willingness to experiment with non-traditional verse forms; Imagists used free verse. A characteristic feature of Imagism is its attempt to isolate a single image to reveal its essence. This feature mirrors contemporary developments in avant-garde art, especially Cubism. Although Imagism isolates objects through the use of what Ezra Pound called "luminous details", Pound's ideogrammic method of juxtaposing concrete instances to express an abstraction is similar to Cubism's manner of synthesizing multiple perspectives into a single image.[5]

Imagist publications appearing between 1914 and 1917 featured works by many of the most prominent modernist figures in poetry and other fields, including Ezra Pound, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), Ford Madox Ford, William Carlos Williams, F. S. Flint, and T. E. Hulme. The Imagists were centered in London, with members from Great Britain, Ireland and the United States. Somewhat unusually for the time, a number of women writers were major Imagist figures.

Pre-Imagism

Well-known poets of the Edwardian era of the 1890s, such as Alfred Austin, Stephen Phillips, and William Watson, had been working very much in the shadow of Tennyson, producing weak imitations of the poetry of the Victorian era. They continued to work in this vein into the early years of the 20th century.[6] As the new century opened, Austin was still the serving British Poet Laureate, a post he held up to 1913. In the century's first decade, poetry still had a large audience; volumes of verse published in that time included Thomas Hardy's The Dynasts, Christina Rossetti's posthumous Poetical Works, Ernest Dowson's Poems, George Meredith's Last Poems, Robert Service's Ballads of a Cheechako and John Masefield's Ballads and Poems. Future Nobel Prize winner William Butler Yeats was devoting much of his energy to the Abbey Theatre and writing for the stage, producing relatively little lyric poetry during this period. In 1907, the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Rudyard Kipling.

The origins of Imagism are to be found in two poems, Autumn and A City Sunset by T. E. Hulme.[7] These were published in January 1909 by the Poets' Club in London in a booklet called For Christmas MDCCCCVIII. Hulme was a student of mathematics and philosophy; he had been involved in setting up the club in 1908 and was its first secretary. Around the end of 1908, he presented his paper A Lecture on Modern Poetry at one of the club's meetings.[8] Writing in A. R. Orage's magazine The New Age, the poet and critic F. S. Flint (a champion of free verse and modern French poetry) was highly critical of the club and its publications. From the ensuing debate, Hulme and Flint became close friends. In 1909, Hulme left the Poets' Club and started meeting with Flint and other poets in a new group which Hulme referred to as the "Secession Club"; they met at the Eiffel Tower restaurant in London's Soho[9] to discuss plans to reform contemporary poetry through free verse and the tanka and haiku and through the removal of all unnecessary verbiage from poems. The interest in Japanese verse forms can be placed in a context of the late Victorian and Edwardian revival of interest in Chinoiserie and Japonism as witnessed in the 1890s vogue for William Anderson's Japanese prints donated to the British Museum, performances of Noh plays in London, and the success of Gilbert and Sullivan's operetta The Mikado (1885). Direct literary models were available from a number of sources, including F. V. Dickins's 1866 Hyak nin is'shiu, or, Stanzas by a Century of Poets, Being Japanese Lyrical Odes, the first English-language version of the Hyakunin Isshū, a 13th-century anthology of 100 waka, the early 20th-century critical writings and poems of Sadakichi Hartmann, and contemporary French-language translations.

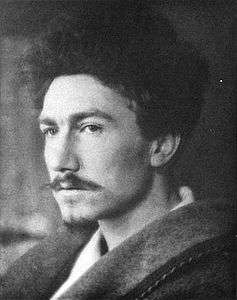

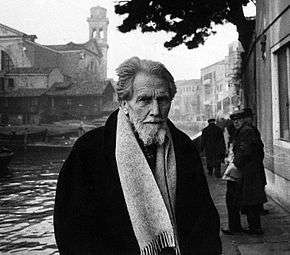

The American poet Ezra Pound was introduced to the group in April 1909 and found their ideas close to his own. In particular, Pound's studies of Romantic literature had led him to an admiration of the condensed, direct expression that he detected in the writings of Arnaut Daniel, Dante, and Guido Cavalcanti, amongst others. For example, in his 1911–12 series of essays I gather the limbs of Osiris, Pound writes of Daniel's line "pensar de lieis m'es repaus" ("it rests me to think of her"), from the canzone En breu brizara'l temps braus: "You cannot get statement simpler than that, or clearer, or less rhetorical".[10] These criteria—directness, clarity and lack of rhetoric—were to be amongst the defining qualities of Imagist poetry. Through his friendship with Laurence Binyon, Pound had already developed an interest in Japanese art by examining Nishiki-e prints at the British Museum, and he quickly became absorbed in the study of related Japanese verse forms.[11]

In a 1915 article in La France, the French critic Remy de Gourmont described the Imagists as descendants of the French Symbolists.[12] Pound emphasised that influence in a 1928 letter to the French critic and translator René Taupin. He pointed out that Hulme was indebted to the Symbolist tradition, via William Butler Yeats, Arthur Symons and the Rhymers' Club generation of British poets and Mallarmé.[13] Taupin concluded in his 1929 study that however great the divergence of technique and language "between the image of the Imagist and the 'symbol' of the Symbolists[,] there is a difference only of precision".[4] In 1915, Pound edited the poetry of another 1890s poet, Lionel Johnson. In his introduction, he wrote

No one has written purer imagism than [Johnson] has, in the line

Clear lie the fields, and fade into blue air,

It has a beauty like the Chinese.[14]

Early publications and statements of intent

In 1911, Pound introduced two other poets to the Eiffel Tower group: his former fiancée Hilda Doolittle (who had started signing her work H.D.) and her future husband Richard Aldington. These two were interested in exploring Greek poetic models, especially Sappho, an interest that Pound shared.[15] The compression of expression that they achieved by following the Greek example complemented the proto-Imagist interest in Japanese poetry, and, in 1912, during a meeting with them in the British Museum tea room, Pound told H.D. and Aldington that they were Imagistes and even appended the signature H.D. Imagiste to some poems they were discussing.

When Harriet Monroe started her Poetry magazine in 1911, she had asked Pound to act as foreign editor. In October 1912, he submitted thereto three poems each by H.D. and Aldington under the Imagiste rubric,[16] with a note describing Aldington as "one of the 'Imagistes'". This note, along with the appendix note ("The Complete Works of T. S. Hulme") in Pound's book Ripostes (1912), are considered to be the first appearances of the word "Imagiste" (later anglicised to "Imagist") in print.[16]

Aldington's poems, Choricos, To a Greek Marble, and Au Vieux Jardin, were in the November issue of Poetry, and H.D.'s, Hermes of the Ways, Priapus, and Epigram, appeared in the January 1913 issue; Imagism as a movement was launched.[17] Poetry's April issue published what came to be seen as "Imagism's enabling text",[18] the haiku-like poem of Pound titled "In a Station of the Metro":

- The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

- Petals on a wet, black bough .[19]

The March 1913 issue of Poetry contained A Few Don'ts by an Imagiste and the essay entitled Imagisme both written by Pound, with the latter being attributed to Flint. The latter contained this succinct statement of the group's position:

Pound's note opened with a definition of an image as "that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time". Pound goes on to state,"It is better to present one Image in a lifetime than to produce voluminous works".[21] His list of "don'ts" reinforced his three statements in "Imagism", while warning that they should not be considered as dogma but as the "result of long contemplation". Taken together, these two texts comprised the Imagist programme for a return to what they saw as the best poetic practice of the past. F. S. Flint commented "we have never claimed to have invented the moon. We do not pretend that our ideas are original."[22]

The 1916 preface to Some Imagist Poets comments "Imagism does not merely mean the presentation of pictures. Imagism refers to the manner of presentation, not to the subject."[23]

Des Imagistes

Determined to promote the work of the Imagists, and particularly of Aldington and H.D., Pound decided to publish an anthology under the title Des Imagistes. It was first published in Alfred Kreymborg's little magazine The Glebe and was later published in 1914 by Alfred and Charles Boni in New York and by Harold Monro at the Poetry Bookshop in London. It became one of the most important and influential English-language collections of modernist verse.[24] Included in the thirty-seven poems were ten poems by Aldington, seven by H.D., and six by Pound. The book also included work by F. S. Flint, Skipwith Cannell, Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, James Joyce, Ford Madox Ford, Allen Upward and John Cournos.

Pound's editorial choices were based on what he saw as the degree of sympathy that these writers displayed with Imagist precepts, rather than active participation in a group as such. Williams, who was based in the United States, had not participated in any of the discussions of the Eiffel Tower group. However, he and Pound had long been corresponding on the question of the renewal of poetry along similar lines. Ford was included at least partly because of his strong influence on Pound, as the younger poet made the transition from his earlier, Pre-Raphaelite-influenced style towards a harder, more modern way of writing. The inclusion of a poem by Joyce, I Hear an Army, which was sent to Pound by W.B. Yeats,[25] took on a wider importance in the history of literary modernism, as the subsequent correspondence between the two led to the serial publication, at Pound's behest, of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in The Egoist. Joyce's poem is not written in free verse, but in rhyming quatrains. However, it strongly reflects Pound's interest in poems written to be sung to music, such as those by the troubadours and Guido Cavalcanti. The book met with little popular or critical success, at least partly because it had no introduction or commentary to explain what the poets were attempting to do, and a number of copies were returned to the publisher.

Some Imagist Poets

_-_Bachrach.jpg)

The following year, Pound and Flint fell out over their different interpretations of the history and goals of the group arising from an article on the history of Imagism written by Flint and published in The Egoist in May 1915.[26] Flint was at pains to emphasise the contribution of the Eiffel Tower poets, especially Edward Storer. Pound, who believed that the "Hellenic hardness" that he saw as the distinguishing quality of the poems of H.D. and Aldington was likely to be diluted by the "custard" of Storer, was to play no further direct role in the history of the Imagists. He went on to co-found the Vorticists with his friend, the painter and writer Wyndham Lewis.[27]

Around this time, the American Imagist Amy Lowell moved to London, determined to promote her own work and that of the other Imagist poets. Lowell was a wealthy heiress from Boston whose brother Abbott Lawrence Lowell was President of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.[28] She loved Keats and cigars. She was also an enthusiastic champion of literary experiment who was willing to use her money to publish the group. Lowell was determined to change the method of selection from Pound's autocratic editorial attitude to a more democratic manner. This new editorial policy was stated in the Preface to the first anthology to appear under her leadership: "In this new book we have followed a slightly different arrangement to that of our former Anthology. Instead of an arbitrary selection by an editor, each poet has been permitted to represent himself by the work he considers his best, the only stipulation being that it should not yet have appeared in book form."[29] The outcome was a series of Imagist anthologies under the title Some Imagist Poets. The first of these appeared in 1915, planned and assembled mainly by H.D. and Aldington. Two further issues, both edited by Lowell, were published in 1916 and 1917. These three volumes featured most of the original poets, plus the American John Gould Fletcher,[30] but not Pound, who had tried to persuade Lowell to drop the Imagist name from her publications and who sardonically dubbed this phase of Imagism "Amygism".[31]

Lowell persuaded D. H. Lawrence to contribute poems to the 1915 and 1916 volumes,[32] making him the only writer to publish as both a Georgian poet and an Imagist. Marianne Moore also became associated with the group during this period. However, with World War I as a backdrop, the times were not easy for avant-garde literary movements (Aldington, for example, spent much of the war at the front), and the 1917 anthology effectively marked the end of the Imagists as a movement.

Imagists after Imagism

In 1929, Walter Lowenfels jokingly suggested that Aldington should produce a new Imagist anthology.[33] Aldington, by now a successful novelist, took up the suggestion and enlisted the help of Ford and H.D. The result was the Imagist Anthology 1930, edited by Aldington and including all the contributors to the four earlier anthologies with the exception of Lowell, who had died, Cannell, who had disappeared, and Pound, who declined. The appearance of this anthology initiated a critical discussion of the place of the Imagists in the history of 20th-century poetry.

Of the poets who were published in the various Imagist anthologies, Joyce, Lawrence and Aldington are now primarily remembered and read as novelists. Marianne Moore, who was at most a fringe member of the group, carved out a unique poetic style of her own that retained an Imagist concern with compression of language. William Carlos Williams developed his poetic along distinctly American lines with his variable foot and a diction he claimed was taken "from the mouths of Polish mothers".[34] Both Pound and H.D. turned to writing long poems, but retained much of the hard edge to their language as an Imagist legacy. Most of the other members of the group are largely forgotten outside the context of the history of Imagism.

Legacy

Despite the movement's short life, Imagism would deeply influence the course of modernist poetry in English. Richard Aldington, in his 1941 memoir, writes: "I think the poems of Ezra Pound, H.D., Lawrence, and Ford Madox Ford will continue to be read. And to a considerable extent T. S. Eliot and his followers have carried on their operations from positions won by the Imagists."

On the other hand, Wallace Stevens found shortcomings in the Imagist approach: "Not all objects are equal. The vice of imagism was that it did not recognize this."[35] With its demand for hardness, clarity and precision and its insistence on fidelity to appearances coupled with its rejection of irrelevant subjective emotions Imagism had later effects that are demonstratable in T. S. Eliot's 'Preludes' and 'Morning at the Window' and in D. H. Lawrence's animal and flower pieces. The rejection of conventional verse forms in the nineteen-twenties owed much to the Imagists' repudiation of the Georgian Poetry style.[36]

Imagism, which had made free verse a discipline and a legitimate poetic form,[2] influenced a number of poetry circles and movements. Its influence can be seen clearly in the work of the Objectivist poets,[37] who came to prominence in the 1930s under the auspices of Pound and Williams. The Objectivists worked mainly in free verse. Clearly linking Objectivism's principles with Imagism's, Louis Zukofsky insisted, in his introduction to the 1931 Objectivist issue of Poetry, on writing "which is the detail, not mirage, of seeing, of thinking with the things as they exist, and of directing them along a line of melody." Zukofsky was a major influence on the Language poets,[38] who carried the Imagist focus on formal concerns to a high level of development. Basil Bunting, another Objectivist poet, was a key figure in the early development of the British Poetry Revival, a loose movement that also absorbed the influence of the San Francisco Renaissance poets. In his seminal 1950 essay Projective Verse, Charles Olson, the theorist of the Black Mountain poets, wrote "ONE PERCEPTION MUST IMMEDIATELY AND DIRECTLY LEAD TO A FURTHER PERCEPTION";[39] his credo derived from and supplemented the Imagists.[40]

Among the Beats, Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg in particular were influenced by the Imagist emphasis on Chinese and Japanese poetry. William Carlos Williams was another who had a strong effect on the Beat poets, encouraging poets like Lew Welch and writing an introduction for the book publication of Ginsberg's Howl (1955).

See also

- Spectrism, a hoax poetic movement satirising Imagism

Notes

- Hughes, Glenn (1931). Imagism and the Imagist. Stanford University Press. (Preface)

- Pratt, William (2001 [1963]). The Imagist Poem: Modern Poetry in Miniature. Story Line Press. ISBN 1-58654-009-2.

- T.S. Eliot: "The point de repère, usually and conveniently taken as the starting-point of modern poetry, is the group denominated 'imagists' in London about 1910." Lecture, Washington University, St. Louis, June 6, 1953.

- Taupin, René (1929). L'Influence du symbolism francais sur la poesie Americaine (de 1910 a 1920). Paris: Champion. Translation (1985) by William Pratt and Anne Rich. New York: AMS.

- Davidson, Michael (1997). Ghostlier Demarcations: Modern Poetry and the Material Word. University of California Press, pp. 11–13. ISBN 0-520-20739-4.

- Grant, Joy (1967). Harold Monro and the Poetry Bookshop. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, p. 28.

- Brooker, p. 48.

- McGuinness, xii.

- Williams, Louise Blakeney (2002). Modernism and the Ideology of History: Literature, Politics, and the Past. Cambridge University Press, p. 16. ISBN 0-521-81499-5.

- Pound, Ezra (1975). William Cookson (ed.). Selected Prose, 1909–1965. New Directions Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8112-0574-0.

- Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard (2011). Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African and Pacific Art and the London Avant Garde. Oxford University Press, pp. 103–164. ISBN 978-0-19-959369-9. Also see Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard (2011). "The Transcultural Roots of Modernism: Imagist Poetry, Japanese Visual Culture, and the Western Museum System". Modernism/modernity 18:1, pp. 27–42; and Cosmopolitanism and Modernism: How Asian Visual Culture Shaped Early Twentieth Century Art and Literature in London. London University School of Advanced Study. March 2012.

- Preface to Some Imagist Poets (1916). Constable and Company.

- Woon-Ping Chin Holaday (Summer 1978). "From Ezra Pound to Maxine Hong Kingston: Expressions of Chinese Thought in American Literature". MELUS. 5 (2): 15–24. doi:10.2307/467456. JSTOR 467456.

- Ming Xie, Ming Hsieh (1998). Ezra Pound and the Appropriation of Chinese Poetry: Cathay, Translation, and Imagism. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8153-2623-6.

- Ayers, David (2004). "H. D., Ezra Pound and Imagism", in Modernism: A Short Introduction. Blackwell Publishers, p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4051-0854-6.

- Monroe, Harriet (1938). A Poet's Life. Macmillan.

- "General William Booth Enters into Heaven by Vachel Lindsay". Poetry Foundation. March 20, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Barbarese, J. T. (1993). "Ezra Pound's Imagist Aesthetics: Lustra to Mauberly" in The Columbia History of American Poetry. Columbia University Press. ISBN 1-56731-276-4.

- DuPlessis, Rachel Blau (2001). Genders, Races, and Religious Cultures in Modern American Poetry, 1908–1934. Cambridge University Press. Excerpted in "On 'In a Station of the Metro'" (Modern American Poetry). Retrieved on August 29, 2010.

- Elder, Bruce (1998). The Films of Stan Brakhage in the American Tradition of Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Charles Olson. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, pp. 72, 94. ISBN 0-88920-275-3.

- Pound (1918). "A Retrospect". Reprinted in Kolocotroni et al., p. 374.

- F. S. Flint letter to J.C. Squire, January 29, 1917.

- Some Imagist Poets (1916). Constable and Company.

- Edgerly Firchow, Peter; Evelyn Scherabon Firchow; Bernfried Nugel (2002). Reluctant Modernists: Aldous Huxley and Some Contemporaries. Transaction Books, p. 32.

- Ellmann, Richard (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press, p. 350.

- Pondrom, Cyrena (1969). "Selected Letters from H. D. to F. S. Flint: A Commentary on the Imagist Period". Contemporary Literature. 10 (4): 557–586. doi:10.2307/1207696. JSTOR 1207696.

- Page, A.; Cowley, J.; Daly, M.; Vice, S.; Watkins, S.; Morgan, L.; Sillars, S.; Poster, J.; Griffiths, T. (1993). "The Twentieth Century". The Year's Work in English Studies. 72 (1): 361–421. doi:10.1093/ywes/72.1.361. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "A(bbott) Lawrence Lowell". Harvard University. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Preface to Some Imagist Poets (1915). Reprinted in Kolocotroni et al, p. 268.

- Hughes, Glenn (1931). Imagism & The Imagists: A Study in Modern Poetry. Stanford University Press.

- Moody, A. David (2007). Ezra Pound: Poet: A Portrait of the Man and His Work, Volume I, The Young Genius 1885–1920. Oxford University Press, p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-957146-8

- Lawrence, D. H. (1979). The Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Cambridge University Press, p. 394.

- Aldington, Richard; Norman Gates (1984). Richard Aldington: An Autobiography in Letters. Oficyna Akademii sztuk pięknych w Katowicach, p. 103.

- Bercovitch, Sacvan; Cyrus R. K. Patell (1994). The Cambridge History of American Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-49733-6.

- Enck, John J. (1964). Wallace Stevens: Images and Judgments. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 11.

- Allott, Kenneth (ed.) (1950). The Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse. Penguin Books. (See introductory note.)

- Sloan, De Villo (1987). "The Decline of American Postmodernism". SubStance. University of Wisconsin Press. 16 (3): 29–43. doi:10.2307/3685195. JSTOR 3685195.

- Stanley, Sandra (1995). "Louis Zukofsky and the Transformation of a Modern American Poetics". South Atlantic Review. 60 (1): 186–189. doi:10.2307/3200737. JSTOR 3200737.

- Olson, Charles (1966). Selected Writings. New Directions Publishing. pp. 17. ISBN 978-0-8112-0335-7.

- Riddel, Joseph N. (Autumn 1979). "Decentering the Image: The 'Project' of 'American' Poetics?". Boundary 2. 8 (1): 159–188. doi:10.2307/303146. JSTOR 303146.

References

- Aldington, Richard (1941). Life For Life's Sake. The Viking Press. (See Chapter IX.)

- DuPlessis, Rachel Blau (1986). H.D.: The Career of That Struggle. The Harvester Press. ISBN 0-7108-0548-9.

- Brooker, Jewel Spears (1996). Mastery and Escape: T. S. Eliot and the Dialectic of Modernism. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-040-X.

- Guest, Barbara (1985). Herself Defined: The Poet H.D. and Her World. Collins. ISBN 0-385-13129-1.

- Jones, Peter (ed.) (1972). Imagist Poetry. Penguin.

- Kenner, Hugh (1975). The Pound Era. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-10668-4.

- Kolocotroni, Vassiliki; Jane Goldman; Olga Taxidou (1998). Modernism: An Anthology of Sources and Documents. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45074-2.

- McGuinness, Patrick (ed.) (1998). T. E. Hulme: Selected Writings. Fyfield Books, Carcanet Press. ISBN 1-85754-362-9 (pages xii–xiii).

- Sullivan, J. P. (ed.) (1970). Ezra Pound. Penguin Critical Anthologies Series. ISBN 0-14-080033-6.

Further reading

- Pound, Ezra (1934). ABC of Reading. New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-0151-1.

- Symons, Julian (1987). Makers of the New: The Revolution in Literature, 1912–1939. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-98007-5.