Hybridization in political election campaign communication

Hybridization comprises the fusion of country- and culture-specific election campaigning methods with contemporary styles and techniques. Originally deriving from biology, where the term hybridizations denotes the process of combining different varieties of organism to create a hybrid, the term is transferred to the field of political communication when a hybrid election campaign arises. One main aspect of this concept is the emphasis on an international comparative perspective. In Globalization theory the term hybridization means the ongoing blending of cultures, which denotes in political campaign communication also the blending of political cultures.

Characteristics

Hybridization in political campaigning is concerned with the diffusion of political communication practices “mediated by cultural factors and accentuated by specific institutional arrangements” and “where country-specific, traditional modes are supplemented with select features of transnationally traded modern practices"

Influence factors

An important role in the development of campaign practices plays the political culture in the specific country. This culture finds expression in the relationship between political culture and political communication as organizing framework for comparing political systems The three key dimensions are the relationship between the media and the political system (e.g. regulations for political ads on TV), the norms that define roles and function of media for society (e.g. publishing of delicate private details of candidates) and relationship between citizens and political system (e.g. political fatigue)

In the process of hybridization “new technologies and techniques are adapted and blended together with preexisting modes of campaigning” Although the rise of the Internet, for example, lead to a variety of political websites of candidates, the preexisting norm of how personal a candidate is shown in campaign, i.e. whether there are information about the personal life of the candidate or not, remains decisive for the shape of the website.

Contextual constraints

There are several influence factors which determinate the way of hybridization, which practice is applied and which not. For example there are no candidate debates in Japan because in the culture-specific background there is a norm which stands for less confrontation between the candidates.

Institutional arrangements are, e.g., party-specific working methods, cultural traditions include for example the importance of political life and private life of president candidates for the public. Other contextual constraints for campaign styles are illustrated in regulatory frameworks like laws against specific campaigning methods like data mining and the media environment itself like the availability of free air-time on television.

Mediating factors in specific countries which influence campaign practices can be characterized as institutional and regulatory factors in three important areas: Electoral system, party system and Mass media|media system.

The following table shows the most important factors shaping the way of hybridization: Electoral system Party system Media system Types, levels and frequencies of elections

Number of parties Dominant type of broadcasting system

Election laws Fragmentation scores Possibility to buy air time on TV

Candidate or party vote Party identification TV consumption

Public vs. private funding of campaigns

Party system polarization Daily newspaper reach

Modus of voter registration

Strength of parties Attitude of journalists towards politics

Table 1:Mediating system factors

Those factors shown in the table interact and shape the way of how the hybridization is practiced in a specific country and the cultural and practices of the existing campaigning culture in that country matter as well. The three top categories Electoral, Party and Media System show in which area the campaign practices are influenced. For example, data privacy protection is a high value in German society and law so the campaign practice of data sourcing is highly frowned upon there.

Earlier approaches

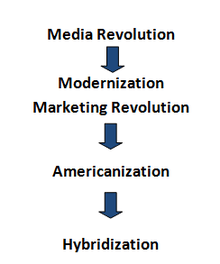

The shift and changes in political campaigning in different countries have been visible for a long time and there have been different explanations in research.

Media revolution

One of the earlier research approaches is the occurrence of a media revolution which came up with the rise of television.[1] Media is seen here as a causal factor for changes in campaigning and political culture: “The mass media are assuming many of the information functions that political parties once controlled. Instead of learning about an election at a campaign rally or from party canvassers, the mass media have become the primary resource of campaign information”.[2]

Modernization and marketing revolution

Another process that is seen as explanatory factor in research is modernization which includes “changes in political culture as a consequence of a prolonged, universal structural change in politics, society and media system”.[3] An example is the ongoing negativity of campaigning as a consequence of an endogenous change [4] i.e., changes in the specific country and culture. Often it is also used as a synonym for professionalization[5] which means for example that major parties use more and more external consultants for campaigning.[6] Often the changes in campaigning are also called marketing revolution. In this approach, change in parties and their relationship to voters leads to the fact that “many major parties turned to experts in marketing and public relations, opinion polling, and other techniques to discover how they could effectively appeal to citizens”.[7]

Americanization

The most prominent approach to explain the diffusion of campaign practices is called Americanization. American campaigning acts as a role model and is the reason for convergence of political communication in Asia, Europe, Africa and Australia to American methods like for example the orientation at marketing strategies.[8] The idea of convergence of campaigning “comprises a targeted, uni-linear diffusion of political communication practices from the United States to other countries”.[9] This approach contains several weak points, for example “it refers only to symptoms and practical patterns of political communication, whereas the institutions of the political system or the organizations and roles of media and political actors are neglected”.[9] The change is caused only external in this approach but not from a social change inside the country and culture.

The Shopping and Adoption Model

To explain the global diffusion of American campaign and marketing techniques there have been two models, the Shopping and Adoption Model.[10] Both models take into respect that American aspects, practices and strategies of campaigning find resemblance in other country’s campaigning. Both use different perspectives to find the causal factors and future developments. The Adoption Model detects a standardization which will lead to a “gradual phase-out of country-specific traditional campaign styles and their substitution by capital-intensive, media- and consultant-driven campaign practices”.[11] Today the Shopping Model is preferred because it focuses on the process of hybridization and proclaims a “country-specific supplementation of traditional campaign practices with select features of the American style of campaigning”.[11] To summarize, the hybridization approach is the evolutionary explanation approach which arose from different earlier ones to explain changes in election campaigning.

Examples: hybridization around the world

Hybridization as a mixture of culture- and country-specific campaign methods and new practices from the U.S. or other countries like image management, which means the focus on the personality of a candidate, can be found in several countries. A number of concrete examples are listed in the following:

In Sweden

In his study Still the Middle Way: A Study of Political Communication Practices in Swedish Election Campaigns (2006) Lars W. Nord examines the change in Sweden in the light of hybridization. He discovers a mixed picture where media are becoming more important both as an arena and an actor in the political communication process.[12] “The transformation process in Sweden is, however, rather slow and does not correspond in any way to the dramatic changes taking place within the electorate and the media system”.[13] Nord names several reasons for Sweden’s particular hybridization: First, he indicates that the political and electoral context in Sweden, which means a proportional and party-based electoral system, compromises “a possible global diffusion of campaign and marketing techniques based upon a two-party system and candidate centered”.[14] Second the Swedish media structure is still politics-friendly and much time and space during election time is spend on more substantial political coverage than on power plays or scandals. As a last reason Nord names the political culture of Sweden where “political parties still thrive on party platforms and manifestos in their campaign activities, while they officially play down political marketing practices”[14] because most of the members and voters expect that. In his conclusion Nord characterizes the hybridization of political communication practices in Sweden by a growing use of marketing tools, although he admits that substantial obstacles to the complete implementation of modern practices still exist.[12] Therefore he identifies existing laws and regulations and, even more, public perceptions of parties, politics, and elections. Nord’s study shows a particular insight how hybridization can look like in a Western European country.

In Ecuador

To examine hybridization processes in a Latin American country, Corres de la Torre and Catherine Conaghan analyzed the election campaign race between presidency candidates Rafael Correa and Alvora Noboa in the year 2006.[15] They did a multi-level-analysis and looked at campaign practices of the candidates like mass rallies and the reports on the candidates in media like in TV shows or newspaper articles. Their results show that there is a hybrid nature of campaigning in Ecuador: They found that both candidates used esp. television as a platform to present their personalities and project negative images of the competitor (e.g. in a TV spot where the other one was pictured as reckless capitalist). Secondly they found a trend towards professionalization. Both candidates used political professionals with considerable experience in presidential elections. “Both camps employed the standard communications tactics, from ‘going negative’ on opponents to the endless repetition of simple, understandable messages as in Noboa’s promise of ‘jobs, jobs, and more jobs.’ The focus on media strategies, however, did not preclude more old-fashioned efforts at grassroots organizing; both organizations recognized the need to establish local networks of supporters for the ground war of political canvassing and getting out the vote on election Day".[16] What both authors stress in their conclusion is that the hybridity in Ecuador is not only a hybridity in politics but also in public life which involves “the candidates’ intensive use of some of the most traditional political rhetorics and practices, namely populism and clientelism".[17]

In Japan

In his study Japanese Lower House Campaigns in Tradition: Manifest Changes or Fleeting Fads? (2009) Patrick Koellner examined if there is temporal change in campaigning practices in Japan.[18] Recently he noticed a significant change in campaigns, like the increasing use of voter-chasing strategies which was earlier very local becoming higher on a national level. For example parties started in 2003 to publish manifesto, i.e., central issues and election main topics, ahead of the election which was new for Japanese party but is an established practice for example in Western European countries.

As a causal factor he names the growing number of independent voters in Japan who are no longer bound to any specific party, so a change in the electorate. He also identifies the mixed electoral system for the House of Representatives of Japan as reason for changing practices because in Japan the voting system for the Parliament has changed recently and so election campaigns did, too. Additionally, he names media- and technology-related developments as factors for new implementation of campaigning practices and comes to the conclusion that “the concurrence of elements of continuity and change in electioneering has led to a ‘hybridization’ of Lower House election campaigns".[19]

Criticism

The wide concept of hybridization covers a broad variety of changes and gives a rough frame for different processes. However, still questions remain and further research is needed in several areas. As most important gap “a lack of clearly specified and standardized independent and dependent variables, and a lack of explanatory hypothesis-based analyses with large aggregated data sets”[20] can be identified. Another important factor which has to be analyzed further is the importance of new media practices especially in the light of changes in Arabic and African countries where institutional and social changes are taking place. And a constraint that should be considered when talking about hybridization is a conclusion Swanson and Mancini made: “it would be wrong to conclude that campaign practices in each country have followed paths which are completely unique".[21]

Notes

- cf. Mancini, & Swanson, 1996.

- Dalton & Wattenberg, 2000, p.11.

- Esser & Pfetsch, 2004, p.12.

- Plasser & Plasser, 2002, p. 17.

- Mancini & Swanson, 1996, p.4.

- cf. Gibson & Römmele, 2006.

- Swanson, 2004, p.49.

- Plasser & Plasser, 2002, p.16.

- Esser & Pfetsch, 2004, p.11.

- Plasser, Scheucher & Senft, 1999, p.105.

- Plasser & Plasser, 2002, p.19.

- cf. Nord, 2006.

- Nord, 2006, p.73.

- Nord, 2006, p.74.

- cf. de la Torre & Conaghan, 2009.

- de la Torre & Conaghan, 2009, p.349.

- de la Torre & Conaghan, 2009, p.350.

- cf. Koellner, 2009.

- Koellner, 2009, p. 121.

- Esser & Strömbäck, 2012, p.304.

- Swanson & Mancini, 1996, p.269.

See also

References

Dalton, R., J., & Wattenberg, M., P. (2000). Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gibson, R., & Römmele, A. (2001). Changing Campaign Communication: A Party-Centered Theory of Professionalized Campaigning. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 6 (4), p. 31-43.

Gurevitch, M., & Blumler, J. G. (2004). State of the art of comparative political communication research. Poised for maturity?. In F. Esser, & B. Pfetsch (Eds.), Comparing political communication: theories, cases, and challenges (pp. 325–343). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Esser, F., & Pfetsch, B. (2005). Comparing political communication: theories, cases, and challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Esser, F. & Strömbäck, J. (2012). Comparing Election Campaign Communication. In F. Esser (Ed.), Handbook of Comparative Communication Research (pp. 289–307). New York: Routledge.

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Americanization, globalization, and secularization: Understanding the convergence of media systems and political communication. In F. Esser, & B. Pfetsch (Eds.), Comparing political communication: theories, cases, and challenges (pp. 25–44). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holtz-Bacha, C. (2000). Wahlkampf in Deutschland. Ein Fall bedingter Amerikanisierung. In K. Kamps (Ed.), Trans-Atlantik – Trans-Portabel? Die Amerikanisierungsthese in der politischen Kommunikation (pp. 44–55). Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Holtz-Bacha, C. (2004). Political campaign communication: Conditional convergence of modern media elections. In F. Esser, & B. Pfetsch (Eds.), Comparing political communication: theories, cases, and challenges (pp. 213–230). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koellner, P. (2009). Japanese Lower House Campaigns in Transition: Manifest Change or Fleeting Fads? Journal of East Asia Studies, 6, p. 121-149.

Mancini, P., & Swanson, D. L. (1996). Politics, media, and modern democracy: Introduction. In D. L. Swanson, & P. Mancini (Eds.), Politics, media and modern democracy. An international study of innovations in electoral campaigning and their consequences (pp. 1–26). Westport: Praeger.

Nord, L., W. (2006). Still the Middle Way: A Study of Political Communication Practices in Swedish Election Campaigns. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11, p. 64-76.

de la Torre, C., & Conaghan, C. (2009). The Hybrid Campaign: Tradition and Modernity in Ecuador’s 2006 Election. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 14, p. 335-352.

Plasser, F., & Plasser, G. (2002). Global political campaigning. A worldwide analysis of campaign professionals and their practises. Westport: Praeger.

Waisbord, S. (1997). Practicas y precios del proselitismo presidential: Apuntes sobre medios y campanas electorales en America Latina y Estados Unidos. Constribuciones, 2, p. 159-182.

Further reading

Blumler, J. G., & Kavanagh, D. (1999). The third age of political communication: Influences and features. Political Communication, 16, p. 209–230.

Esser, F. & Pfetsch, B. (2004), Comparing political communication: theories, cases and challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Esser, F. & Strömbäck, J. (2012). Comparing Election Campaign Communication. In F. Esser (Ed.), Handbook of Comparative Communication Research (pp. 289–307). New York: Routledge.

Mancini, P., & Swanson, D. L. (1996). Politics, media, and modern democracy: An international study of innovations in electoral campaigning and their consequences. Westport: Prager.

Plasser, F., & Plasser, G. (2002). Global political campaigning. A worldwide analysis of campaign professionals and their practises. Westport: Preager.