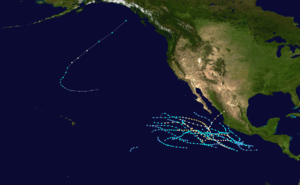

Hurricane Olivia (1975)

Hurricane Olivia was considered the worst hurricane to hit Mazatlán, Sinaloa since 1943, in addition to being the strongest landfalling and costliest hurricane of the 1975 Pacific hurricane season. Olivia formed on October 22 to the south of Mexico, quickly intensifying into a tropical storm. The storm moved northwestward initially, followed by a northeast turn. On October 23, Olivia attained hurricane status, and the next day reached Category 3 intensity on the Saffir-Simpson scale just before moving ashore Mazatlán in northwest Mexico. Olivia destroyed 7,000 houses in the region, leaving 30,000 people homeless, and damage totaled $20 million (1975 USD, $95 million 2020 USD). The hurricane killed 30 people, 20 of them from drowning in shrimp boats.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Olivia approaching landfall on October 24 at 2215 UTC | |

| Formed | October 22, 1975 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 25, 1975 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Fatalities | 30 direct |

| Damage | $20 million (1975 USD) |

| Areas affected | Mexico |

| Part of the 1975 Pacific hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

The origins of Olivia were from an extended area of convection, or thunderstorm activity, that persisted southwest of Mexico in late October. Following the development of a circulation, the system formed into a tropical depression early on October 22 about 430 mi (690 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Colima. The depression quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Olivia as it tracked northwestward, although further strengthening was slowed. The circulation became much better defined on October 23 and after Olivia turned northeastward, it attained hurricane status that evening.[1][2]

After reaching hurricane status, Olivia accelerated to the north-northeast. Several ships crossed its path, encountering strong winds and rough waves. On October 24, a Hurricane Hunters flight observed an elliptical eye and winds of 91 mph (146 km/h). Further intensification occurred, and around 0500 UTC on October 25 Olivia made landfall on Mazatlán, Sinaloa with peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and gusts to 140 mph (230 km/h); this made Olivia a major hurricane, or a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. It quickly dissipated after moving ashore.[1][2]

Preparations and Impact

| Hurricane | Season | Wind speed | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patricia | 2015 | 150 mph (240 km/h) | [3] |

| Madeline | 1976 | 145 mph (230 km/h) | [4] |

| Iniki | 1992 | [5] | |

| Twelve | 1957 | 140 mph (220 km/h) | [6] |

| "Mexico" | 1959 | [6] | |

| Kenna | 2002 | [7] | |

| Olivia | 1967 | 125 mph (205 km/h) | [6] |

| Tico | 1983 | [8] | |

| Lane | 2006 | [9] | |

| Odile | 2014 | [10] | |

| Olivia | 1975 | 115 mph (185 km/h) | [11] |

| Liza | 1976 | [4] | |

| Kiko | 1989 | [12] | |

| Willa | 2018 | [13] |

Prior to Olivia making landfall, the Mexican military evacuated about 50,000 people from low-lying areas.[14] Accurate forecasts from satellite and ship data were credited with preventing a significant death toll,[1] although the population did not know of the storm's approach until a day before landfall. Officials advised ships to return to port for safety, and the threat of the storm canceled a baseball game.[15] As Olivia moved ashore, it produced locally heavy rainfall, peaking at 7.28 in (185 mm) in Pueblo Nuevo, Durango. The heaviest rains occurred in a narrow region where the hurricane made landfall, although precipitation of around 1 in (25 mm) reached as far south as Michoacán, 340 mi (550 km) south of the landfall location.[16] Winds in Mazatlán reached 138 mph (222 km/h).[17]

The combination of strong winds and heavy rainfall destroyed about 7,000 homes in Mazatlán and 14 nearby villages,[1] with 10,000 houses damaged to some degree.[18] Many of the destroyed homes were poorly built, and the hurricane's passage left 30,000 people homeless; the storm victims were housed in schools, churches, and other buildings not damaged during the storm.[17] Most buildings in the city were affected, with storm debris covering streets.[15] Across the region, the hurricane cut power and water services, and also disrupted the transportation infrastructure by damaging highways and railroads.[14] The airport was also heavily damaged, with flights suspended into the city. Most windows at the airport were blown-out, and 14 small planes were overturned. The strong winds also downed trees, while heavy rainfall resulted in flooding.[19]

Olivia was considered the worst storm in Mazatlán since a hurricane in 1943,[20] and following the storm, the city was declared a disaster zone.[18] Near the coastline and in tourist areas, damage reached $4 million (1975 USD, $19 million 2020 USD).[1] Across its path, Olivia killed 30 people and left 500 injured,[1] 17 of them severe.[19] Offshore, 20 of the deaths occurred when three shrimp boats were wrecked.[1] The winds damaged a wall at a prison, killing two prisoners and allowing others to escape.[14] Overall damage totaled $20 million (1975 USD, $95 million 2020 USD).[1]

Olivia is one of only three major hurricanes on record to strike Mazatlán, the others being the 1943 hurricane, as well as another in 1957; in addition Hurricane Tico in 1983 came close to striking the city.[21] Reconstruction began immediately, and the Secretariat of National Defense quickly deployed food and water to the storm victims. By a day after the storm's passage, the Mexican Navy sent two ships worth of relief supplies to Mazatlán, including water, medicine, and rescue equipment.[15] Three days after the storm passed through the region, relief workers began cleaning up the storm debris.[19]

References

- Robert A. Baum (April 1976). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1975" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. p. 487. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Kimberlain, Todd B.; Blake, Eric S.; Cangialosi, John P. (February 1, 2016). Hurricane Patricia (pdf) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- Emil B., Gunther (April 1977). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1976". Monthly Weather Review. Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center. 105 (4): 508–522. Bibcode:1977MWRv..105..508G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1977)105<0508:EPTCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Central Pacific Hurricane Center (1993). The 1992 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 24, 2003.

- Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Franklin, James L. (December 26, 2002). Hurricane Kenna (pdf) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Emil B., Gunther; Cross, R. L. (July 1984). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1983". Monthly Weather Review. Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center. 112 (7): 1419–1440. Bibcode:1984MWRv..112.1419G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1984)112<1419:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Knabb, Richard D. (November 30, 2006). Hurricane Lane (pdf) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Cangialosi, John P.; Kimberlain, Todd B. (December 19, 2014). Hurricane Odile (pdf) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- Robert A., Baum (April 1976). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1975". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Service Forecast Center. 104 (4): 475–488. Bibcode:1976MWRv..104..475B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1976)104<0475:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Mayfield, Britt Max (November 18, 1989). Hurricane Kiko (Report). Preliminary Report. Miami, Florida: National Weather Service. p. 6. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Brennan, Michael J. (April 2, 2019). Hurricane Willa (pdf) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Staff Writer. "Hurricane Leaves Two Dead". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- Enrique Vega Ayala (2009-10-20). ""Olivia": Cuatro horas de miedo" (in Spanish). Noroeste. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- David M. Roth (2009-07-23). "Hurricane Olivia - October 21-26, 1975". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- Staff Writer (1975-10-26). "30000 Homeless, 25 dead in Hurricane". Tri City Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- Staff Writer (1975-10-27). "Hurricane kills 27". The Deseret News. United Press International. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- John Schmidt (1975-10-28). "Farmers View Wreckage". The Calgary Herald. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- Staff Writer (1975-10-28). "Storm Damage Cleanup Begins". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- R. G. Handlers and S. Brand (June 2001). "Tropical Cyclones Affecting Mazatlan". NRL Monterrey. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2009-06-07.