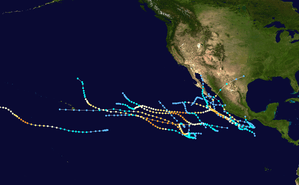

Hurricane Hilary (1993)

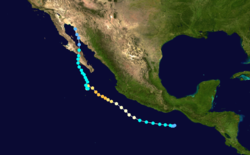

Hurricane Hilary was a Category 3 hurricane that caused significant flooding in the Midwestern United States in August 1993. A westward moving tropical depression gradually developed on August 17 south of the Mexican coast, attaining hurricane status two days later. The storm further intensified into a Category 3 hurricane, attaining peak winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). By August 23, the hurricane nearly stalled while interacting with Tropical Storm Irwin. Executing a small counter-clockwise loop, Hilary degraded to tropical storm intensity and took a northerly track for the remainder of its existence. The storm made two landfalls in Mexico, one in Baja California Sur on August 25 and one in Sonora the following day. Tropical cyclone warnings and watches were issued for much of the southern Mexican coastline; however, they were later discontinued when the threat ended, but were issued again when the system posed a threat to the Baja California Peninsula. Hilary dropped in excess of 5 in (130 mm) rain along its path in some areas, and flash flooding in California and Iowa.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Hilary on August 20, 1993 | |

| Formed | August 17, 1993 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 27, 1993 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 957 mbar (hPa); 28.26 inHg |

| Fatalities | None |

| Areas affected | Mexico, California, Iowa |

| Part of the 1993 Pacific hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

Several small areas of convection developed in association with a tropical wave on August 14 near Central America. Over the next two days, the convection migrated across Central America, and then entered the Gulf of Tehuantepec on August 16. The next morning, Tropical Depression Nine-E formed south of an upper-level low that was located in the Gulf of Mexico. Banding features slowly increased in coverage, and on August 18, the depression intensified, becoming Tropical Storm Hilary about 100 mi (160 km) south of the Pacific coast of Mexico.[1] Hilary steadily gained strength,[2] but its outflow remained restricted.[3] Moving northwest on a track parallel to the coast of Mexico at around 10 mi (16 km) due to a complex steering pattern,[1] Hilary was initially poorly organized and its low-level circulation was tough to find. The storm failed to intensify further[4] until August 19, when the storm was upgraded into a hurricane after the cyclone developed very cold cloud tops.[1]

Even though most computer models expected Hilary to remain offshore, meteorologists suggested there was a possibility of making landfall near Manzanillo.[5] The next day, an eye formed;[1] subsequently, Hilary reached Category 2 intensity on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[6] By the time, the hurricane had grown into a large cyclone with gale-force winds extending out 130 mi (210 km) from the center.[1] Under weak steering currents, Hilary became a major hurricane, a cyclone with winds of 111 mph (190 km/h) or higher, early on August 21.[7] Shortly thereafter, Hilary reached its peak intensity with winds of 120 mph (155 km/h). Around this time, Hurricane Hilary developed a 15 mi (24 km) eye. Later that day, however, the eye had shrunk to about 9 mi (14 km) in diameter.[1] The eye, which was very well-defined, was surrounded by a central dense overcast, a large mass of deep convection.[8]

Shortly after its peak, Hurricane Hilary's motion became unsteady. After nearly stalling, the hurricane turned to the west on August 22, only to become nearly stationary again the next day. Slowly executing a small counter-clockwise loop, Hilary underwent a Fujiwhara interaction with Tropical Storm Irwin which was several hundred miles southeast.[1] Meanwhile, Hilary began to weaken, by early on August 22, the eye became poorly defined and convection diminished.[9] The eye dissipated within 12 hours, and the winds quickly diminished to 85 mph (130 km/h).[10] Later that day, the thunderstorm activity became partially exposed from the center,[11] and on August 23, Hilary was downgraded to a tropical storm due to lack of organization.[12]

The interaction continued to weaken Hilary, leaving it with little thunderstorm activity and winds of just 40 mph (60 km/h) on August 24, before resuming a northerly motion. Around this time, Hilary finally absorbed Irwin. While Hilary began to traverse cooler waters, the environment became more favorable. Upon developing a 200 mb anticyclone, Hilary began to revive based on data from satellite imagery and ship reports. Tropical Storm Hilary made landfall in Baja California Sur on two separate occasions as a strong tropical storm on August 25. Weakening over land, the cyclone regenerated deep convection over the Gulf of California. As a tropical depression, Hilary made its final landfall on August 26 just west of Hermosillo in Sonora. While most of the mid to upper level moisture associated with the storm got pulled inland by a shortwave trough, the low level center dissipated in the northern Gulf on August 27.[13]

Preparations and impact

Due to Hilary's proximity to Mexico on August 20, hurricane watches were issued for much of the southern coastline; however, they were later discontinued. Once the system began its northward track, further watches and warnings were issued for the Baja California Peninsula and the Gulf of California coastline.[14] Heavy rains, with a maximum recorded amount of 11.35 in (288 mm) in Derivorda Jale, Colima, were accompanied the storm. Along the Baja California Peninsula, a statewide rainfall total of 4.33 in (110 mm) fell in Huerta Vieja. However, no damage or loss of life took place.[13][15] Winds along the peninsula were strong, though not as strong as Hurricane Calvin, a hurricane which struck the peninsula during July 1993.[16]

The outer bands of Hurricane Hilary also brought localized downpours to parts of California, resulting in flash floods.[17] In Arizona, 3.75 inches (95 mm) of rain fell on Green Valley, and 3.50 inches (89 mm) of precipitation was recorded at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, resulting in flash flooding.[18] Hilary produced a surge of moisture that dropped over 25% of the summer rainfall in portions of New Mexico.[19] The remains of Hilary combined with a cold front to produce widespread flooding across the Midwestern United States.[20] About 10 in (250 mm) fell in some areas of Iowa, forcing rivers and streams to overflow its banks. Hundreds of people evacuated their homes.[21]

See also

References

- Rappaport, Edward (September 27, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Preliminary Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- Lixon, Avila; Burr (August 19, 1993). "Tropical Storm Hilary Discussion 5". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Lixon, Avila (August 19, 1993). "Tropical Storm Hilary Discussion 7". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Pasch, Robert; Burr (August 19, 1993). "Tropical Storm Hilary Discussion 8". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Lawrence, Miles (August 20, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 10". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Rapport, Edward; Burr (August 20, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 13". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Lawrence, Miles (August 21, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 14". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Mayfield, Max (August 21, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 15". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Lawrence, Miles (August 22, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 18". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Mayfield, Max (August 22, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 20". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Mayfield, Max (August 22, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 21". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Mayfield, Max (August 22, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Discussion 23". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Rappaport, Edward (September 27, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Preliminary Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- Rappaport, Edward (September 27, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Preliminary Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. p. 7. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- Rappaport, Edward (September 27, 1993). "Hurricane Hilary Preliminary Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- "Mariners Weather Log". Environmental Data and Information Service. 38: 22. 1994.

- National Weather Service (February 2010). "A History of Significant Weather Events in Southern California" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- "Hurricane Hilary 1993". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Weather Service, Tucson Regional Office. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- Kristen L. Corbosiero; Michael Dickinson; Lance Bosart (August 2009). "The Contribution of Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones to the Rainfall Climatology of the Southwest United States". Monthly Weather Review. 137 (8): 2419. Bibcode:2009MWRv..137.2415C. doi:10.1175/2009MWR2768.1.

- Google News (September 1, 1993). "How Emily got where it was". The Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. Associated Press. p. 3. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Google News (August 30, 1993). "New round of evacuations start with Iowa flooding". The Herald Journal. Des Moines, Iowa. Associated Press. p. 3. Retrieved November 20, 2011.