Hunza District

Hunza District (Urdu: ضلع ہنزہ) is one of the districts of the Gilgit-Baltistan territory in northern Pakistan. It was established in 2015 by the division of Hunza–Nagar District in a bid to establish more administrative units in the region.[1] Aliabad is the administrative centre of the district.

Hunza District | |

|---|---|

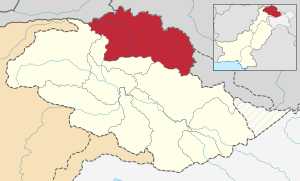

Map of Gilgit–Baltistan, with Hunza district highlighted. | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Dependent territory | Gilgit–Baltistan |

| Established | July 1, 1970 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 38,000 km2 (15,000 sq mi) |

| Population (1998) | |

| • Total | 243,324 |

| • Density | 6.4/km2 (17/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

Geography and history

The Hunza district represents the northernmost region of the Indian subcontinent, adjoining China's Xinjiang province. It contains the historic pass through the Karakoram mountains (Killik, Mintaka, Khunjeerab and Shimshal passes) through which trade and religion passed between India and Central Asia/China for centuries. The present day Karakoram Highway passes through the Khunjerab Pass to enter Xinjiang.

Historian Ahmad Hassan Dani has established that the Sakas (Scythians) used the Karakoram route to invade Taxila. The Sacred Rock of Hunza has petroglyphs of mounted horsemen and ibex, along with Kharosthi inscriptions that list the names of Saka and Pahlava rulers.[2] The rock also contains inscriptions from the Kushan period, showing the Saka and Kushan suzerainty over the Hunza and Gilgit regions.[3]

.png)

Hunza began to separate from the Gilgit region as a separate state around 997 AD, but decisive separation occurred with the establishment of the Ayash ruling family in the 15th century. The neighbouring Nagar state also separated in the same manner, and internecine battles between the two states were endemic.[4] Following the invasion of Kashmir by the Moghul nobleman Mirza Haidar Dughlat, the Mir of Hunza established diplomatic relations with Kashgaria (based in Yarkand). After Kashgaria came under Chinese control, he continued the relations by paying an annual tribute of gold dust to the Chinese government in Yarkand. In return for this token tribute, Hunza enjoyed territorial rights in the Raskam Valley and grazing rights in Taghdumbash Pamir.[5][6]

After the British suzerainty was established over the Kashmir region in 1846, the British made Hunza subject to the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. Thus Hunza was in the anomalous position of being subject to two sovereign powers at the same time, immensely complicating the relations between British India and the Chinese empire. The practice of tribute to China was eventually stopped in 1930.[6]

After the Partition of India into the present day India and Pakistan in 1947, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir acceded to India to in order to defend his State against a Pakistani tribal invasion. There was a rebellion in Gilgit, overthrowing the Maharaja's authority. The Mir of Hunza subsequently acceded to Pakistan, but the accession was never formally accepted due to the Kashmir dispute in the United Nations. Pakistan regards the whole of Gilgit and Baltistan regions as de facto parts of Pakistan, even though India also claims the entire Kashmir region.

Administration

Deputy Commissioner

District administration is supervised by a Deputy commissioner (DC), with an assistant commissioner as a sub-ordinate.

Police

Hunza police is commanded by a Superintendent of Police (SP).

References

- "Dividing governance: Three new districts notified in G-B - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- Puri 1996, pp. 185–186.

- Harmatta 1996, p. 426.

- Dani 1998, pp. 223, 224.

- Pirumshoev & Dani 2003, p. 243.

- Mehra, An "agreed" frontier 1992, pp. 1–14.

Bibliography

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1998), "The Western Himalayan States", in M. S. Asimov; C. E. Bosworth (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV, Part 1 — The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century — The historical, social and economic setting (PDF), UNESCO, pp. 215–225, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- Harmatta, János (1996), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to AD> 250 (PDF), UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5

- Mehra, Parshotam (1992), An "agreed" frontier: Ladakh and India's northernmost borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press

- Pirumshoev, H. S.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003), "The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States", in Chahryar Adle; Irfan Habib (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. V — Development in contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century (PDF), UNESCO, pp. 225–246, ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1

- Puri, B. N. (1996), "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians", in János Harmatta (ed.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to AD> 250 (PDF), UNESCO Publishing, pp. 184–201, ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5