Hovander Homestead Park

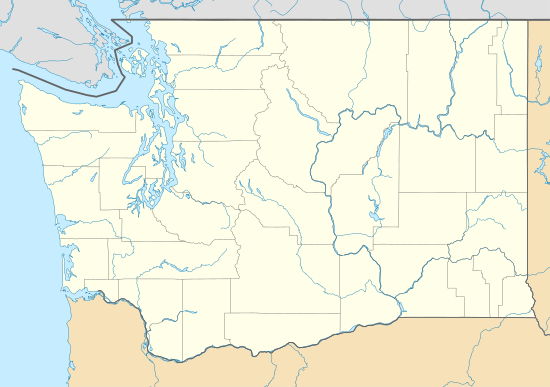

Hovander Homestead Park, a roughly 350 acre county park that includes Tennant Lake,[2] is located adjacent to Ferndale, Washington and borders the Nooksack River.[2][3] It is named for the Hovander family, who immigrated from Sweden to the property in 1898 and designed the farmhouse, barn, and other buildings, some of which include distinctive architectural features.[3][4] The homestead was owned by the Hovander family until 1969 when the Whatcom County government purchased the land from Hokan Hovander's son, Otis, and it officially became a county park in 1971.[5]

Hovander Homestead | |

Hovander Homestead farmhouse | |

| |

| Location | 5299 Neilson Rd., Ferndale, Washington |

|---|---|

| Area | 60 acres (24 ha) |

| Built | 1901 |

| Architect | Hovander,Holan O. |

| Architectural style | Stick/eastlake |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001990[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 16, 1974 |

The park has been preserved to show the lives of 20th-century pioneers in the Northwest, as well as to preserve the history of the Hovander family.[6] Hovander Homestead Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[7][8] In 1978, the park received the National Trust for Historic Preservation award for the preservation of a significant and historic site.[3]

Hovander family

Hokan (also spelled Hakan and Holan in various sources) Hovander, an immigrant from Skåne, Sweden, moved to the Pacific Northwest with his wife Louisa Leontine Johansdatter Lof and several children in 1897.[9] Hovander, an architect and bricklayer, initially settled in Seattle but later moved to Ferndale with his family to farm the land.[10] He arrived in Ferndale in 1898 and paid $4,000 ($122,928 in 2018) for 60 acres (24 ha) on the Nooksack River that was purchased from Betsey Nielson.[11] The property included two log cabins, farm animals, and farm equipment.[12]

Farmhouse

In June 1899, Hovander finished his plan for the house and ordered 52,000 board feet of fir and cedar.[13] All of this wood was soaked in linseed oil for two years to cure,[14] which has led to the wood not needing treatment since.[6] In spring 1901, the building of the house began, and the carpentry work was finished by Carl Lindgren, a Swede.[15]

In the late 19th century, it was common in the Northwest for settlers to imitate the style of architecture from their previous homes.[16] Many aspects of Scandinavian architecture are present within the house, including the egg and dart trim design, representing fertility, modified to fit a traditional geometric Scandinavian artistic design.[17] Another example is the Star of David openwork design on the porch railings, a very popular design of that time period.[18] Additional examples of Scandinavian influence include the linseed oil treatment, large and open rooms with windows and doorways that are in proportion to the size of the room, and high ceilings.[19]

There are no fireplaces in the farmhouse, and it is known to be one of the first houses in Whatcom County to utilize a central heating system.[6] Hovander designed the house with doors between each room that can open and close in multiple directions to direct the flow of heat throughout the house.[20] The house was completed in 1903, and had 6,800 square feet (630 m2) with three bedrooms, a library, a dining room, and a kitchen.[3]

The barn

At the same time that Hovander was planning and designing the farmhouse, he was also planning the barn.[21] While the farmhouse is representative of Swedish architecture, Hovander's design for the barn was influenced by the barn designs he saw in the United States.[22] Hovander disliked the common Swedish barn design of the time, as they were typically small, and was instead fascinated with the size and loft design of barns that he had seen in the United States.[23] He designed the barn as a large space with a high ceiling, and hired men from Bellingham to build it.[24]

Hokan painted the barn with a mixture of oil and iron rich soil which oxidized to a dull red, a practice that reportedly originated in Scandinavia.[25] The Hovander Homestead is built on the Nooksack River's flood lands and Hokan had to account for the natural landscape by building the barn and the house on raised platforms.[6]

Hovander homestead

The Hovanders soon began farming the land after moving into the log cabins on the property.[26] The family's first crop was oats, but later they also farmed sweet corn, hay, dried fruit, and pork.[27][28] Two fruit orchards came with the property, and the apple orchard is present at the park today.[29] The family members also made their own soap and candles.[30][31]

Leontine was trained as a cook in Sweden and cooked for the family and the hired hands on the farm.[32] It was tradition for Swedish women to take over and manage the farm whenever their husband was not at the farm, so Leontine was well-known and respected by the farm workers.[33] The Hovander children attended school in Ferndale and they would walk along pioneer trails or row across the river to get into town.[34]

Not long after arriving in Ferndale, Hovander began building a Holstein dairy herd from the 12 cows that came with the homestead.[35] By 1919, the herd had grown to over 50 cows, but the entire herd contracted tuberculosis from an unknown source and had to be culled.[36] The Hovanders then replaced the Holsteins with Guernseys.[37] Due to his deteriorating health, Hokan Hovander died in 1915, but his family continued to run the farm.[38]

Eight years after the cows died, the two youngest Hovanders, Vera and Ada, both came down with tuberculosis.[39] Ada recovered, but Vera died in 1929.[40] Leontine died, at 77 years old, a few years later in 1936.[41] After the death of their sister and mother, Otis, Charles, and Angelo operated the farm adding raspberries, sugar beets, and chickens to the farm products.[42] Otis was the last Hovander to live on the farm and he continued the Hovander legacy until 1971.[43]

County park

In 1969, the Hovander homestead was purchased for $60,000 by Whatcom County Parks and Recreation.[44] Otis lived in the house until 1971 when the park officially opened to the public, and he died in 1979.[45][46] Between 1969 and 1971, much effort was put into repairing and improving the house and the barn so that they could be transformed for public visitation.[47] The farm tools and most of the items in the farmhouse on display were used by the family.[48] Eventually, animals were moved in to help finish the homestead environment of the park.[49]

The demonstration garden

In the following years, a demonstration garden was installed to show what the Hovander's garden may have looked like, and to provide landscaping for all the area directly surrounding the farmhouse.[6] The demonstration garden is currently maintained through Whatcom County Parks and Recreation as well as the Washington State University Extension Service and the Master Gardener Foundation.[50] The garden is experimental and used for teaching.[51] The produce that is grown is given to the local food bank.[52]

Tennant Lake

The Tennant Lake section of the park includes an interpretive center, fragrance garden, wildlife viewing tower and boardwalk with viewing platforms that is built over the wetlands adjacent to the lake.[2]

Activities

The park has many visitors each year. There are historical tours led by a park supervisor or historian during the late spring and summer on the property.[3][53] Families bring their children to the park to see the animals and to play on the playground. There are also several benches located throughout the park, and a trail along the river between Hovander Homestead Park and Tennant Lake that promotes views of Mount Baker along the way.[54] Many events are held at Hovander Homestead Park such as weddings, family get togethers, birthday parties, and photography sessions for multiple different types of events due to the unique architecture of the buildings and the landscape surrounding the park.[6] There are annual events held at the park such as Ski to Sea and the Highland Scottish Games.[55]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- "Whatcom County Parks and Rec: Hovander Homestead Park". Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- "Hovander Homestead Park (Whatcom County)". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- Hovander Family and Park Papers, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, Heritage Resources, Western Washington University, Bellingham WA.

- Campbell, Jeff; Dragoo, Heidi; Galligan, Darby; Lyons, Salina; Robinson, Beth; Rudback, Matias (March 2002). Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Tennant Lake and Hovander Homestead Park. (Western Washington University, Huxley College of the Environment. p. 2. OCLC 50585988.

- Jacoby, Jill, Hovander Park Ranger, interview, March 2, 2019.

- Roger Ellingson (April 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Hovander Homestead". National Park Service. Retrieved July 27, 2019. With 5 accompanying pictures

- Campbell et al., Environmental and Social Impact, 2.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 19–22, 27.

- Cyr, 29.

- Cyr, 31.

- See note 29.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 36.

- Cyr, 41.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 39.

- Dole, Philip (1997). "The Calef's Farm in Oregon, A Vermont Vernacular Coming West". In Carter, Thomas (ed.). Images of an American Land: Vernacular Architecture in the Western United States. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780826317292.

- Cyr, 29.

- Cyr, 40.

- Cyr, 40-41.

- See note 40.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 48.

- Cyr, 49.

- See note 44.

- See note 44.

- Cyr, 53.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 31.

- Cyr, 31.

- Cyr, 35.

- Cyr, 31.

- See note 53.

- Hovander Family and Park Papers, Western Washington University.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 35.

- Cyr, 35.

- Cyr, 36.

- See note 58.

- Cyr, 63.

- Cyr, 64.

- Cyr, 61.

- Cyr, 65.

- See note 63.

- See note 63.

- Cyr, 66.

- See note 66.

- Cyr, 83.

- Campbell et al., Environmental and Social Impact, 2.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 83.

- Cyr, 85.

- Cyr, 89.

- Cyr, 94.

- See note 74.

- Cyr, Hovander Homestead Research Manual, 96.

- Cyr, 96.

- Campbell et al., Environmental and Social Impact, 2.

- Campbell et al., Environmental and Social Impact, 17.

- Campbell et al., Environmental and Social Impact, 18.