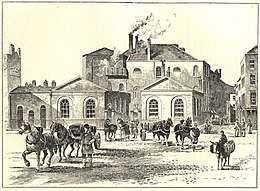

Horse Shoe Brewery

The Horse Shoe Brewery was an English brewery located in central London. It was established in 1764 and became a major producer of porter. It was the site of the London Beer Flood in 1814, which killed eight people after a porter vat burst. The brewery was closed in 1921.

%3B_Horse_Shoe_Brewery.jpg)

History

Early history

.jpg)

The brewery tap, the Horseshoe, was established in 1623, and was named after the shape of its first dining room.[1] The brewery was named after the tavern.[1] The Horse Shoe Brewery was established in 1764 on the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street.[2] By at least 1785 it was owned by Thomas Fassett.[1] By 1786–87, it had the 11th largest output of porter of any London brewery, producing 40,279 barrels a year.[1]

By 1792 the brewery was owned by John Stephenson the younger, son of John Stephenson the elder.[1] In 1794, after Stephenson's early death, the brewery ownership passed to Edward Biley.[1] Biley ran the brewery until January 1809 when he was joined in partnership by John Blackburn and Edward Gale Bolero.[1] Towards the end of 1809 the brewery was acquired by Henry Meux, who had been a partner in one of the largest of London’s porter brewers, Meux Reid of the Griffin Brewery in Clerkenwell.[1] The company traded under the name Henry Meux & Co.[3] The horseshoe became part of the Meux identity and was incorporated into its logo. By 1811 annual production had reached 103,502 barrels, making it the sixth largest brewer of porter in London.[1] In 1813/14 the Horse Shoe brewery merged with or acquired Clowes & Co of Bermondsey.[1]

1814 disaster

On the 17 October 1814, corroded hoops on a large vat at the brewery prompted the sudden release of about 7,600 imperial barrels (270,000 imp gal) of porter.[4] The resulting torrent caused severe damage to the brewery's walls and was powerful enough to cause several heavy wooden beams to collapse.[5] The flood's severity was exacerbated by the landscape, which was generally flat. The brewery was located in a densely populated and tightly packed area of squalid housing (known as the rookery). Many of these houses had cellars. To save themselves from the rising tide of alcohol, some of the occupants were forced to climb on furniture.[5] Several adjoining houses were severely damaged, and eight people killed.[4][nb 1] The accident cost the brewery about £23,000, although it petitioned Parliament for about £7,250 in excise drawback, saving it from bankruptcy.[4]

Post 1814

After the disaster, the brewery continued to be one of the largest producers of porter in London throughout the 19th century.[1] Sir Henry Meux, second Baronet took ownership of the company in 1841 following the death of his father.[3] Production of ale began in 1872.[6] Meux employed three partners to manage the brewery: Richard Berridge, Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks and William Arabin.[7] In 1878, Henry Bruce Meux and Marjoribanks (now Lord Tweedmouth) took over management of the company, which they renamed Meux's Brewery Company Ltd when they registered it as a public company in 1888.[3] Henry Bruce Meux died childless in 1900, and his wife, Valerie, Lady Meux, inherited his share of the brewery.[7] She took a liking to Hedworth Lambton, and he received her share of the Horse Shoe Brewery when she died in 1910.[7]

The Horse Shoe Brewery closed in 1921.[2] By this time the site covered 103,000 square feet (9,600 m2), but there was no available land to expand.[8] Production was transferred to the Thorne Brothers' Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, which the company had bought in 1914.[2] The Nine Elms brewery was renamed the Horse Shoe Brewery.[2] The original Horse Shoe Brewery was demolished in 1922, and in 1928–29 the Dominion Theatre was erected on the site.[1]

In 1956, Meux merged with Friary, Holroyd and Healy of Guildford to form Friary Meux,[2] which went into liquidation in November 1961 and the company was acquired by Allied Breweries in 1964.[7] The Horse Shoe Brewery ceased to brew in 1966.[7] Friary Meux was revived by Allied in 1979 as a brand name for its public houses, but disappeared after Allied's pubs were sold to Punch Taverns in 1999.[1]

The former brewery tap is now a branch of Dorothy Perkins, but there are still traces of the Meux brand in London. Notable, until demolition in 2015, was the "Meux's Original London Stout" logo on the side of the derelict The Sir George Robey public house in Seven Sisters Road near Finsbury Park station.[9]

References

- Footnotes

- A contemporary report describes several fatalities; a woman and her daughter, the latter carried "through a partition" and "dashed to pieces"; a female servant in the local Tavistock Arms pub suffocated. The names given are Ann Saville, about 35 years old; Eleanor Cooper, between 15 and 16 years old, servant to Mr Hawse at the Tavistock Arms; Hannah Barnfield, four-and-a-half years old; Mrs Butler, her daughter, grand daughter, and three others, names unknown. Three brewery workers were rescued. One person was dug out alive, two brothers were severely injured. Several people were reported missing.[5]

- Notes

- So what REALLY happened on October 17 1814? | Zythophile

- Lesley Richmond; Alison Turton (1990). The Brewing Industry: A Guide to Historical Records. Manchester University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7190-3032-1.

- The National Archives | Access to Archives

- Hornsey 2003, p. 450

- Dreadful Accident, The Times, hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 19 October 1814, p. 3

- "Sum06.qxp" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- Oxford DNB

- The Times, 23 February 1922, p.?

- "The history of London's 10 greatest live music venues". History Extra. BBC History Magazine. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Bibliography

- Hornsey, Ian Spencer (2003), A History of Beer and Brewing, Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 0-85404-630-5