Holy Trinity Church, Sunderland

Holy Trinity Church (sometimes Church of the Holy Trinity or Sunderland Parish Church) was an Anglican church[1] in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. It was opened in 1719 as the church for the newly created Parish of Sunderland,[2] and served the local community until dwindling numbers forced its closure in 1988. It has since been in the ownership of the Churches Conservation Trust who have preserved the space and converted it into a community cultural hub.

| Holy Trinity Church | |

|---|---|

| Sunderland Parish Church | |

| |

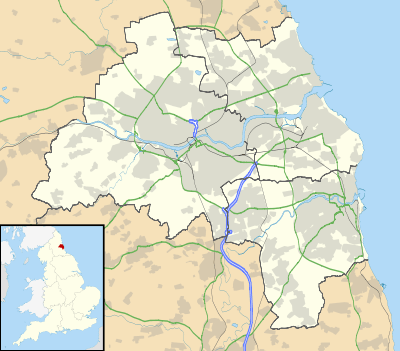

Holy Trinity Church Holy Trinity Church within Tyne and Wear | |

| 54.907765°N 1.368648°W | |

| OS grid reference | NZ 40575 57189 |

| Location | Sunderland |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| History | |

| Status | Parish Church |

| Founded | 1719 |

| Dedication | The Holy Trinity |

| Consecrated | 5 September 1719 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Preserved |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed |

| Designated | 8 May 1950 |

| Style | Baroque |

| Years built | 1718 - 1719 |

| Groundbreaking | 1718 |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Sunderland |

| Diocese | Durham |

History

Origins

In 1712, with the port of Sunderland growing rapidly, the local St. Michael's church at Bishopwearmouth was rapidly becoming too small to serve the growing population.[3] Some local merchants came together and started an appeal to build a new church in the east end of the city, and a site on the town moor was chosen.

Because of the rapid growth of the population, it was also decided that a new parish should be created, and on 9 March 1719 an act of parliament was passed to create the Parish of Sunderland[4][5] (thus the church is sometimes referred to as Sunderland Parish Church). The Bishop of Durham of the time, Nathaniel Crew gave his consent, as did Reverend James Bowes D.D.[4]

Design

The architect of the original church is not known for certain, although there are reports of involvement from William Eddy[6][7] (a well-known local architect) and Daniel Newcombe, who would be appointed the first rector of the church.

The building itself has a Baroque style, brick built and with stone mouldings surrounding the doors and windows. The original building was without apse, although this would later be added (see below), and from the outside is described by Whellan as "plain and unprepossessing".[note 1]

Inside, the building is described by Whellan as "handsome",[8] with the aisles of pews being separated from the central nave by seven pillars on each side, each being capped with a corinthian-style capital. His full description reads:

The interior is handsome, and comprises a nave and chancel, and aisles, the latter of which are separated from the Nave by seven elegant pillars on each side, with Corinthian capitals. The communion table occupies a recess, covered by a dome supported in front by two Corinthian columns. There are galleries on each side, and at the west end of the nave; the front of the latter is charged with the royal arms, and those of Lord Crewe, Bishop of Durham. Above the gallery is a smaller one for the accommodation of the choir.

— William Whellan, History, Topography, and Directory of the County Palpatine of Durham...[8]

Opening

Following the start of groundwork in 1718, the church building was completed the next year, such that on 5 September 1719 the consecration of the premises took place;[10] prior to this, however, on 2 June 1719, the first recorded marriage took place at the church, of Jonathan Chambers and Elizabeth Hutchinson.[11]

1700s

In 1735, Daniel Newcombe, the rector of the church who almost certainly had been involved in the original design of the building, decided to add an apse to the eastern end. This would give the building a chancel, which it had lacked until this point. The apse was large, near circular, and featuring a large venetian window; it still stands as part of the building today. Newcombe paid for the extension with his own money.[1]

1800s

The church started the nineteenth century with a new roof in 1803, which included its raising so that a new gallery could be added.[3][note 2]

Jack Crawford Memorial

.jpg)

Jack Crawford, the "Hero of Camperdown", was a sailor aboard HMS Venerable in 1797, during the Battle of Camperdown. Venerable took fire damaging its mast, which lowered the flag of Admiral Duncan - recognised as the sign of surrender - so Crawford scaled the remnants of the mast and nailed the Admiral's flag back to the top.

Crawford was well celebrated for his act of heroism, and the people of Sunderland awarded him a silver star. In the coming years, however, he fell into poverty and was killed by a cholera outbreak in 1831.

In 1888, Holy Trinity Church erected a headstone in its graveyard in his honour.

The sailor who heroically nailed Admiral Duncan's flag to the main-top-callant-mast of H.M.S. Venerable, after it had been shot away, in the glorious action off Camperdown, October 11th 1797.

Jack Crawford was born in the pottery-bank Sunderland 1775, and died in his native town 1831, aged 56 years.— Jack Crawford Memorial, Holy Trinity Churchyard

This was followed two years later by a statue of commemoration in Mowbray Park.

1900s

The 1900s started with the church being re-glazed,[6] before community life began to degrade and the number of churchgoers in the east end of Sunderland diminished.[10]

Closure

The congregation continued to diminish throughout the 20th century, until on 26 June 1988 the church was forced to close, and transferred to the Redundant Churches Fund[10] (now known as the Churches Conservation Trust). The building itself needed extensive and costly repairs, and indeed to this day the Trust are still undertaking repairs.[12]

Present Day

elevation.jpg)

No longer in use as a place of worship, the building these days goes by the name of The Canny Space, a community venue and cultural arts centre. Restoration work is still underway, with most of the money being fundraised; as of 2015, £1,341,014 had been raised towards the project.[12]

The project's Creative Director role has been filled by noted local musician Dave Stewart, former member of Eurythmics.[12]

Notes

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holy Trinity, Sunderland. |

References

- Kirtlan, Norman. "Places of Worship in Old Sunderland" (PDF). Sunderland Antiquarians. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- BBC Wear Online. "Holy Trinity Church - photo gallery (image 1)". Archived from the original on 9 November 2012.

- Ross, David. "Sunderland, Holy Trinity Church". Britain Express. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Main Papers". The National Archives. UK Parliamentary Archives. March 1719.

- "Sunderland, Co. Durham". The National Archives. Lambeth Palace Library. 1719.

- Historic England. "CHURCH OF HOLY TRINITY (1208056)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Seagull City: Sunderland's Literary and Cultural Heritage". University of Sunderland Blogs: Seagull City. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Whellan, William (1856). History, Topography, and Directory of the County Palpatine of Durham, comprising a general survey of the county, with separate historical, statistical, and descriptive sketches of all the towns, boroughs, ports, parishes, chapelries, townships, willages, wards & manors. To which are subjoined a history and directory of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and a list of the seats of the nobility and gentry (1856 ed.). Whittaker & Co. (London). p. 662. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Joiner, Paul. "Sunderland". GenUKI. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Holy Trinity Church (The East End Of Sunderland)". Wearside Online. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- Pears, Brian (17 October 1996). "Marriages from the Sunderland Registers (1719-1749)". GenUKI. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Creating a 'Canny Space' in Sunderland". Churches Conservation Trust. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

elevation.jpg)