History of the Diablada

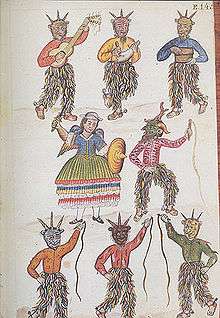

The Diablada or Danza de Diablos (English: Dance of Devils) is a dance created characterized by the mask and devil suit worn by the dancers.[1]

The origin of the Diablada is a matter of dispute between the countries of Bolivia and Peru.[2] Three main locations exist for the possible origin of the dance. These places are:

- Oruro, Bolivia: Its earliest record found in pre-Hispanic times, the dance of "Llama llama"in worship of the Uru god Tiw, dance subsequent ironically devoted Aymara language of the Urus dance dressed as devils, as recorded by Ludovico Bertonio. Ethnohistorical development process of disguise and the dance of Diablada fall into three periods, according to the document sent of Carnaval de Oruro to Organization of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) proclaimed as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity: Periods of 1606 to 1789, 1789 to 1944 y 1944 to 1960.

- Juli, Peru: The Diablada would have been introduced in 1576 to the native Lupakas people of Juli, located near Lake Titicaca in the Altiplano of present-day Puno, Peru; and from there it allegedly spread to other parts of the Spanish domain in the Americas.[3]

Origin of the denomination

The name was consolidated in a historical process of acceptance of the "Dance of devils" Native-Miners to the whole society of Oruro, this process covers the period from 1789 to 1944 where groups of "parades of devils" be called "Diablada." Finally in 1904 created the primeval "Diablada" with the label "The Great Traditional Authentic Diablada Oruro", with music, dress, choreography and plot defined. This period culminated with the founding of new groups of Diabladas in 1944, consolidating the denomination. Currently this definition is in the dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy of Language.

Diablada. f. Typical dance from the region of Oruro, Bolivia, named after the mask and the devil costume worn by dancers. II 2. Mex. prank (II minor mischief.)

— Dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy of Language

Origin of the dance

Its earliest record found in pre-Hispanic times, the dance of "Llama llama" dance subsequent ironically devoted Aymara language of the Urus dance dressed as devils, as recorded by Ludovico Bertonio.

With the arrival of the Spanish in this region in 1535 and the Augustinians in 1559 with the Virgin of Candelaria, it begins to produce an acculturation of religions and cultures.

Ethnohistorical development process of disguise and the dance of Diablada fall into three periods, according to the document sent of Carnaval de Oruro to Organization of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco).

- 1606 to 1789: Historical period the founding of the Villa de San Felipe de Austria by Mr. Manuel de Castro Castillo and Padilla in a space called Uru Uru (Hururu now Oruro), which survives in part the cult of Imps ( name called) to "uncle" of mine that is slowly becoming a cult mixed to "Virgin of Socavón (Virgin of Candelaria) - Uncle of mine (Wari)."

- 1789 to 1944: Officially the image of the Virgin would be enthroned as from the date his image venerated by miners would be dressed as devils, including the archangel San Miguel. By 1818 the cure Montealegre Unveils "The Story of the Diablada", in 1891 finally ends the construction of the chapel of the Tunnel. And by 1904 was born the primeval "Diablada" with the tagline of "The Great Traditional Authentic Diablada Oruro." Diablada starting to travel inside and outside the country since 1915 to show its spectacular choreography, music and costume.

- 1944 to 1960: During this period Diabladas form new groups in 1944 such as: Artistic and cultural fraternity the "Diablada", in June of that year the Traditional set Folk "Diablada Oruro" then the "Circle of Arts and Letters." In 1956 he founded the "Diablada Railway" and finally in 1960 the "Artistic Diablada Urus". Diabladas also travel inside and outside the country showing the rich culture of Oruro, resulting in the founding of similar groups in other geographies of the continent.

...The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro...

— Proclamation of "Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity" to the "Carnival of Oruro", UNESCO 2001

Native American roots

The debate about the patrimonial identity of the Diablada concerns its roots as well. Chilean and Peruvian organizations suggest that since this dance is inspired in the Andean civilizations previous to the formation of the current national borders, it should belong equally to the three nations and other Andean states such as Argentina and Ecuador as well. Bolivian cultural organizations and government label this as an "unlawful cultural heritage appropriation" and consider that the declaration of the Carnaval de Oruro as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity gives Bolivia and the city of Oruro support on this claim.[4] Bolivian scholars such as the professor of ethnomusicology and cultural heritage, Diego Echevers Tórrez, express that the Diablada is not the mere representation of the devils in a defined space, but constitutes the cultural heritage of the city of Oruro with specific actors and environment.[5]

Aymaran roots theory

The scholars who defend the theory of Juli (Peru) identify the roots of this dance with the Aymaran traditions of the Lupakas. Based on the written accounts of 16th-century historian and writer Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, the Lupaka natives of Juli in the year 1576 presented their version of the Autos Sacramentales taught to them by Spanish Jesuit priests.[3] According to the director of the cultural group Yuyachkani of Peru, Miguel Rubio Zapata, the dance holds Native American roots from the cult of Anchanchu, a pre-Hispanic Aymara deity. Furthermore, rearchers Peter McFarren, Sixto Choque, and Teresa Gisbert state that the Diablada has roots to the Aymaran narrative of the Myth of the Supaya.[6]

Uru roots theory

After the declaration of the Carnaval de Oruro as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on 18 May 2001, the UNESCO delegated their ex-ambassador in Bolivia, Ivés de la Goublaye de Menorval, the task to be the moderator of the project and handed a form to the Bolivian authorities to be filled in coordination with historians and folklorists, such as Ramiro Condarco Morales, Mario Montaño Aragón, Fernando Cajías, Alberto Guerra Gutiérrez, Javier Romero, Elías Delgado, Carlos Condarco Santillán, Marcelo Lara, Zenobio Calizaya, Zulma Yugar, Walter Zambrana and Ascanio Nava.

The document elaborated by this group is based in the theory that the modern Diablada has roots in the ancient rituals performed 2000 years ago by the Uru civilization. The study makes reference to a deity named Tiw who was the protector of the Urus in mines, lakes and rivers and, in the case of Oruro (or Uru-uru), the owner of caves and rocky shelters. The Urus worship this deity with the dance of the devils being the Tiw himself the main character, later this name was Hispanicized as Tío (English: uncle), and as product of the syncretism, the Tiw represented the figure of the devil regretting and becoming devotee of the Virgin of Socavón.[7]

During the times of the Tahuantinsuyu, the four administrative entities known as suyus had their own representative dances during the Ito festival, a festivity once celebrated throughout the entire empire but, according to the historian José Mansilla Vázquez, who based on manuscripts of Fray Martín de Murúa, says that these festivities were outlawed during the Viceroyalty of Peru with the exception of Oruro which, for being considered an important miner city in the 16th century, counted with some privileges and the Spanish authorities looked to the other way allowing this festivity persist in this city, adapting itself later into the Spanish traditions between the Carnestolendas and the Corpus Christi becoming into the Carnaval of Oruro over the centuries.[8]

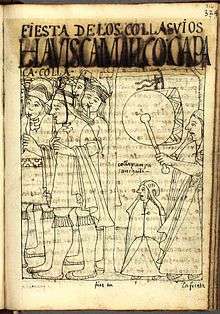

The ancient authors, Fray Martín de Murúa and Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala make reference in their works to the different dances of the area, including the dance of the Llama llama, name given by the Aymaras to refer to the Urus dressed as dancing demons, as it was recorded by Ludovico Bertonio. This dance was performed during the Ito festivities by the representatives of the region known as Urucolla, a sub-region of the south-eastern suyu of Collasuyu located in the lake system of the Department of Oruro between the basins of the lakes Poopó and Coipasa, where the Uru civilization had the city of Oruro as their main social centre, becoming together with Nazca and Wari one of the most ancient cities in the Andean world.[8][9]

The supporters of this theory consider that the Uru mythology is reflected in the symbolism of the Diablada. The legend behind the importance of the city of Oruro as an ancient sacred place for the Urus tells the story of the chthonic deity Wari, which in the Uru language means soul (Uru: hahuari). He, after hearing that the Urus were worshiping Pachacamaj, represented by Inti, unleashed his revenge by sending plagues of ants, lizards, toads and snakes, animals considered sacred in the Uru mythology. But they were protected by the Ñusta who adopted the figure of a condor, defeating the creatures petrifying them and becoming sacred hills in the four cardinal points of the city of Oruro; these animals are also often represented in the traditional masks of the Diablada.[10][11][12]

...//...The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro.//...

— Proclamation of "Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity" to the "Carnival of Oruro", UNESCO 2001

Spanish influence

One of the most referenced studies about the Diablada is the 1961 book of Julia Elena Fortún, La danza de los diablos (The dance of the devils), in which the theory of a relationship between this dance and a Catalan dance named Ball de diables, was suggested; more specifically with the elements used in the localities of Penedès and Tarragona.[13][14] Julia Elena Fortún, unlike other historians in the Peruvian side, disagrees with the idea of considering the Diablada as a product of the introduction of the autos sacramentales in the Andes, because among the ones studied by her, the thematic of the devil and his temptations was not contemplated.[15]

Autos sacramentales Theory

In 2003, the newspaper Correo and José Morales Serruto, coordinator of cultural activities of the Asociación Nativa Puno (Native Association Puno), suggested that the dance of the Diablada was originated in the Peruvian city of Juli during a representation of the autos sacramentales in the year 1576 to the Aymaran kingdom of the Lupacas.[3]

Historian Mercedes Serna observes that as soon as the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire was achieved, there was a sudden increase in the amount of Autos Sacramentales presented in the Spanish colonies. Jose Miguel Oviedo records that by the year 1560 contests were held for religious theatrical presentations.[17] This representation was documented in the 17th century book Comentarios Reales of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega where it reads:[17]

The argument about those words of the book of Genesis: "I shall put enmities between you and the woman, etc... and she will break your head herself". Being represented by young Indians and boys in a town named Sulli. And in Potosí a dialog of faith was recited, for which more than twelve thousand Indians were present. In the Cuzco another dialog was represented about the Child Jesus, where all the greatness of that city was felt. Other was represented in the city of Kings, in front of the chancellorship and all the nobility of the city and innumerable Indians...

— Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, Comentarios Reales

Garcilaso de la Vega further mentions that the Jesuit priests taught the Auto Sacramental comedy by writing it in Aymara, and the natives of Juli later presented their version of the religious dance to the priests and, later, presented a dialogue to the rest of the Spanish population in such a way that it “changed the opinion that up to that point had regarded the natives as being dumb, rude, or incapable.”[17]

This same information is used by other authors, such as the Peruvian scholar Nicomedes Santa Cruz and the Bolivian anthropologist Freddy Arancibia Andrade, to suggest that the Spanish influence was spread to Oruro from the southern Bolivian region of Potosí. Andrade considers that the Diablada recovers the steps of rebellion and combat of the ritual of Tinku mixed with the biblic vision introduced by the Spanish conquerors in the miner region of Aullagas starting in the year 1538.[18][19]

Another piece of information collected by Andrade is that in 1780 the army of Tomás Katari wore demon suits to attack the towns of Macha, Pocoata, Colquechaca, Aullagas and San Pedro de Buena Vista, giving more strength to the syncretism and represents the appearance of the tinku-devil. After the silver era in Bolivia, the miners went to Uncía to work for the tin company of Simón Iturri Patiño and during the Bolivian federal war, the miners migrated to Oruro where in 1904 they were allowed to dance for the Virgin of Socavón.[18]

Ball de diables theory

The Ball de diables has origins in a 12th-century entremés representing the struggle between the good and the evil where the figure of the archangel Saint Michael and his angels battled the forces of evil represented by Lucifer and his demons. This act was performed in the wedding banquet of the Barcelona count, Ramón Berenguer IV with the princess Petronila, daughter of the king of Aragón and Catalonia in the year 1150.[14]

In a study presented in 2005 by the Catalan scholar Jordi Rius i Mercade, member of the Ball de Sant Miquel i Diables de la Riera (board of the Ball de diables in Spain) and editor in chief of the specialized magazine El Dragabales during the Symposium of the Catalan Discovery of America, states that the traditional dances and short plays performed during the celebration of Corpus Christi in Spain were adopted by the Christian church to teach their doctrines to the Native Americans; their festivities were readapted to the new calendar and their deities were redefined acquiring demoniac forms representing the evil fighting against the divine power. According to Rius i Mercade, the Ball de diables was the most suitable for this purpose. In this study, he identifies three Latin American dances that contain similar elements to the Catalan Ball de diables; the Diablada of Oruro, Baile de Diablos de Cobán in Guatemala and Danza de los diablicos de Túcume in Peru.[14]

The Diablada of Oruro represents the tale of the struggle between the archangel Saint Michael and Lucifer, the she-devil China Supay and devils accompanying them. Ruis i Mercade suggests that this was a tale presented by the parish priest Ladislao Montealegre of the city of Oruro in 1818 inspired in the Catalan Ball de diables.[14]

Colonial history

During the colonial times in the region, from the 15th century till the first half of the 19th century, the ancient Andean beliefs were blended with the new Christian traditions. The traditions adopted new iconography and the celebrations adopted a new meaning during the Latin American wars of independence.

From the worship of the Sun to the Virgin of Candlemas

With the advent of the Inca state religion the inhabitants of the Island of the Sun (Spanish: Isla del Sol) were replaced by ministers in worship of the sun (Inti) and the city of Copacabana located in the Bolivian side of the Lake Titicaca had been repopulated by forty-two different nations of mitimaes and became one of the most important landmarks for the constant pilgrimage to the sanctuary; with the migration, two social classes were created in this area, the newcomers became Anansaya (upper) and the indigenous people Urinsaya (lower).[20]

The selection of the Virgin of the Candlemas as the patroness of Copacabana was a sign of the power structures established by the Incas in the area. In the year 1582 a frost threatened to destroy the crops, and the inhabitants decided to build an altar to a Christian figure, but there was a dispute because the Anansayas insisted to use the Virgin of the Candlemas since Francisco Tito Yupanqui had already sculpted her image while the Urinsayas wanted it use the image of Saint Bartholomew instead. But the Anansayas' wishes were imposed in the enthronement of the Virgin of Copacabana and the foundation of a brotherhood.[20]

Independence and the transition to the Carnival

The cult of the Virgin of the Candlemas, was then spread throughout the Andes reaching, Oruro and to the west to Puno. In Oruro there is a Sanctuary in honour of the Virgin of Socavón (or Sanctuary of the Virgin of the Mineshaft) who was originally the Virgin of Candlemas traditionally honoured on 2 February, like in Puno, but later the date was moved to Carnival; this transition is product of the Bolivian War of Independence. [21]

There is a legend that says that on the Saturday of Carnival in 1789 a bandit known as Nina-Nina or Chiru-Chiru was mortally wounded in a street fight and before dying he was confronted by the Virgin of the Candlemas. Some versions state that he used to worship a life-size image of the Virgin painted in a wall of a deserted house, some say that the painting miraculously appeared on the wall of the bandit's own house after his death. And the legend is concluded with the tale of the troupe of devils dancing in honour of the Virgin in the next year's Carnival. The present sanctuary in Oruro was completed in 1891.[21]

However, according to the Ph D in religious studies and Executive Director of the Wisconsin Humanities Council at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Max Harris, this legend is related to a historical reality. During the Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II, which started in Cusco and spread along the Andean highlands, Oruro experienced a brief but bloody revolution as well. Pushed by the fear of being target of the indigenous revolution, the majority Creole on the night of Saturday, 10 February 1781, attacked the minority ruling class of the peninsular-born Spaniards (Spanish: chapetones) . With the arrival of the Indigenous army the Creoles made an alliance.[21]

On 15 February, a messenger arrived in Oruro with orders from Túpac Amaru II. He instructed his army to respect churches and clergy, to do no harm to Creoles, and to prosecute none but chapetones. And assured the victory by entering in La Paz "by Carnival (por Carnestolendas)", the Indigenous occupation of Oruro started to retreat leaving several thousands of deaths. But during March and April they launched more attacks to the city this time against the Creoles and the remaining Spaniards who unified forces to repel them.[21]

Harris observes that the Carnival of the year of 1781, fell on 24 February, placing Oruro's occupation exactly halfway between Candlemas and Carnival, making the situation in Oruro in Harris' words, "carnivalesque". Religious processions duelled with secular parades. Europeans and Creoles disguised as Indigenous, cases like a Spaniard resorting to cross-dressing tin a vain attempt to save his life and thousands of armed men in the streets of the colonial city. By 19 February people in the city regardless of the conflict continued celebrating and, throughout Carnival, the city markets were full of robbers selling the looted gold and silver back to its owners or to cholos and mestizos. By 1784 it was customary to rejoice, dance, play, and form comparsas (companies of masqueraders) for the Carnival in Oruro.[21]

Harris considers that with this background is that the legend of the Virgin of the Mineshaft in 1789 appeared favouring the rebellion as they worshiped the Virgin of Candlemas while the chapetones used to worship the Virgin of the Rosary. Under the beliefs of the revolutionaries, the Virgin of the Socavón tolerated the indigenous deities or devils and, according to Harris, if the legend is correct, by 1790, Oruro's miners had moved Candlemas to Carnival and added indigenous gods, masked as Christian devils, to the festivities.[21]

In 1818, Oruro's parish priest, Ladislao Montealegre, wrote the play Narrative of the seven deadly sins, where according to Harris and Fortún, borrowed elements of the Catalan Ball de diables like the female devil, Diablesa in the Catalan dance and China supay in the Diablada and where the Devil leads the Seven Deadly Sins into battle against the opposing Virtues and an angel. Harris suggests that Montealegre may have wanted to represent the threat of rebellion and the historical context with this play.[21]

A generation later, in 1825 after Bolivia achieved its independence, the Diablada and the Carnival adopted a new meaning for Oruro's residents. Two of the Diablada dance squads and the street from where the parade starts are named after Sebastian Pagador, one of the Creole heroes of the uprising. And the main square which is in the route of the Carnival to the Virgin of the Mineshaft temple is named Plaza 10 de febrero (10 February square) remembering the date of the uprising.[21]

References

- Real Academia Española (2001). "Diccionario de la Lengua Española - Vigésima segunda edición" [Spanish Language Dictionary - 22nd edition] (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

Danza típica de la región de Oruro, en Bolivia, llamada así por la careta y el traje de diablo que usan los bailarines (Typical dance from the region of Oruro, in Bolivia, called that way by the mask and devil suit worn by the dancers).

- Moffett, Matt; Kozak, Robert (21 August 2009). "In This Spat Between Bolivia and Peru, The Details Are in the Devils". The Wall Street Journal. p. A1. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Morales Serruto, José (3 August 2009). "La diablada, manzana de la discordia en el altiplano [The ''Diablada'', the bone of contention in the Altiplano]" (Interview) (in Spanish). Puno, Peru: Correo. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Perú dice que la diablada no es exclusiva de Bolivia" [Peru says that the Diablada is not exclusive of Bolivia]. La Prensa (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia: Editores Asociados S.A. 14 August 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Echevers Tórrez 2009

- McFarren, Peter; Choque, Sixto; Gisbert, Teresa (2009) [1993]. McFarren, Peter (ed.). Máscaras de los Andes bolivianos [Masks of the Bolivian Andes] (in Spanish). Indiana, United States: Editorial Quipus. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- A.C.F.O. 2001, p.3.

- A.C.F.O. 2001, pp.10-17.

- Guaman Poma de Ayala 1615, p.235.

- Claure Covarrubias, Javier (January 2009). "El Tío de la mina" [The Uncle of the mine] (in Spanish). Stockholm, Sweden: Arena y Cal, revista literaria y cultural divulgativa. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- Ríos, Edwin (2009). "Mitología andina de los urus" [Andean mythology of the Urus] (in Spanish). Oruro, Bolivia: MiCarnaval.net. Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010. External link in

|publisher=(help) - Ríos, Edwin (2009). "La Diablada originada en Oruro - Bolivia" [The Diablada originated in Oruro - Bolivia] (in Spanish). Oruro, Bolivia: MiCarnaval.net. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010. External link in

|publisher=(help) - Fortún 1961, p. 23.

- Rius I Mercade 2005

- Fortún 1961, p. 24.

- Feliciano, Wilma (22 September 2004). "El culto subversivo en "Los Diablicos de Túcume", danza dramática peruana" [The subversive cult "The little devils of Túcume", dramatic Peruvian dance] (in Spanish). Tarragona, Spain: Junta del Ball de Diables www.balldediables.org. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- De la Vega, Garcilaso; Serna, Mercedes (2000) [1617]. "XXVIII". Comentarios Reales [Royal Commentaries]. Clásicos Castalia (in Spanish). 252 (2000 ed.). Madrid, Spain: Editorial Castalia. pp. 226–227. ISBN 84-7039-855-5. OCLC 46420337.

- Arancibia Andrade, Freddy (20 August 2009). "Investigador afirma que la diablada surgió en Potosí [Investigator affirms that the ''Diablada'' emerged in Potosí]" (Interview) (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- Santa Cruz, 2004, p. 285.

- Salles-Reese 1997, pp. 166-167.

- Harris 2003, pp. 205-211.