History of rugby union in Wales

Rugby Union has a long history in Wales. Today it holds tier one status with the IRB. However, compared to Scotland, England, and Ireland, it was a latecomer on the international scene, and was not initially successful. Rugby union is the national sport of Wales, and is a great influence on Welsh culture.

Early history and 19th century

Pre-Codification Football

Rugby-like games have a long history in Wales, with games such as cnapan being played for centuries.[1] Cnapan originated in, and seems to have remained largely confined to, the western counties of Wales, especially Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire. According to George Owen of Henllys, in his Description of Pembrokeshire (1603), cnapan had been "extremely popular in Pembrokeshire since greate antiquitie [sic]".[2] Cnapan was one of the traditional ball games played to celebrate Shrovetide and Eastertide in the British Isles.[2][3] These games were the forerunners of the codified football games first developed by Public Schools which led to the creation of Association football and Rugby football in the 19th century. Cnapan continued to be played until the rising popularity of rugby resulted in the game falling into decline.

Early rugby football

Rugby seems to have reached Wales in 1850, when the Reverend Professor Rowland Williams brought the game with him from Cambridge to St. David's College, Lampeter,[4] which fielded the first Welsh rugby team that same year.

Rugby initially expanded in Wales through ex-pupils of the Welsh colleges settling, or students from English colleges and universities returning to the larger industrial hubs of South Wales. This is reflected in the first clubs to embrace the sport in the early to mid-1870s, with Neath RFC widely recognised as being the first Welsh club. The strength of Welsh rugby developed over the following years, which could be attributed to the 'big four' South Wales clubs of Newport (who lost only seven games under the captaincy of Llewellyn Lloyd between the 1900/01 and 1902/03 seasons[5]), Cardiff, Llanelli (who lost just twice in 1894 and 1895) and Swansea. With the coming of industrialisation and the railways, rugby too was spread as workers from the main cities brought the game to the new steel and coal towns of south Wales. Pontypool RFC formed 1868 came to be a stronghold of the game dominating the unprofessional club rugby scene in the 1970s and 1980s.Merthyr formed in 1876, Brecon in 1874, Penygraig in 1877; as the towns adopted the new sport they reflected the growth and expansion of a new industrial Wales.[6]

In the 19th century as well as the established clubs there were many 'scratch' teams populating most towns, informal pub or social teams that would form and disband quickly. Llanelli, as an example, in the 1880s was home not only to Llanelli RFC, but also to Gower Road, Seasiders, Morfa Rangers, Prospect Place Rovers, Wern Foundry, Cooper Mills Rangers, New Dock Strollers, Vauxhall Juniors, Moonlight Rovers and Gilbert Street Rovers.[7] These teams would come and go, but some would merge into more settled clubs which exist today, Cardiff RFC was itself formed from three teams, Glamorgan, Tredegarville and Wanderers Football Clubs.

The South Wales Football Club was established in 1875[8] to try to incorporate a standard set of rules and expand the sport and this was succeeded by the Welsh Football Union which was formed in 1881.[9] With the forming of the WFU (which would become the Welsh Rugby Union in 1934), Wales began competing in recognised international matches, with the first game, against England, also in 1881.[10] The first Welsh team although fairly diverse in the geography of the clubs represented, did not appear to truly represent the strength available to Wales. The team was mainly made up of ex-Cambridge and Oxford university graduates and the selection was heavily criticised in the local press after the crushing defeat by England.[9]

By the end of the 19th century, a group of exciting Welsh players began to emerge, including Arthur Gould, Dick Hellings, Billy Bancroft and Gwyn Nicholls; players that would be regarded as the first super-stars of Welsh rugby and would usher in not only the first golden era of Welsh rugby, but would also see the introduction of specialised positional players.

Twentieth century

Arrival of Rugby League

The schism with Rugby league had far more effect in northern England, than in Wales, although there were attempts to introduce it. Defections to the other code were not uncommon by Welsh players, and Welsh rugby league is more deeply rooted than its Scottish and Irish counterparts.

The Northern Union's administrators began to ponder the possibilities of international competitions against an English representative side. The first attempt met with a lack of public interest, and the first scheduled Northern Union international, also became the first postponed Northern Union international. It was rescheduled for the 5 April 1904. The team opposing England was labelled Other Nationalities and consisted of Welshmen and a few Scots. The Other Nationalities proved too strong, defeating the English 9 - 3. In 1905, England gained back some credibility with a 21 - 11 win.

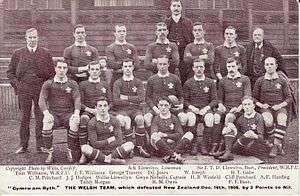

In 1907 a professional version of the "All Blacks" rugby team from New Zealand (nicknamed the All Golds by Australian press) toured England in what became the first set of international games played under the new NU rules. The All Golds had not played under the Northern Union rules and underwent a week of intensive training. The first Wales international league game took place at Aberdare on 1 January 1908 played against the All Golds. Wales went on to defeat New Zealand 9-8, the winning try scored by former Wales rugby union international Dai Jones.

In 1907, the Welsh Northern Union was formed in Wrexham, but the Northern Union refused it affiliation as they wanted the body located in the South of Wales and the WNU soon folded. In 1907 two Welsh clubs Ebbw Vale RLFC and Merthyr Tydfil RLFC joined the Northern Union and also competed in the Challenge Cup.

During the 1908-09 season, there were sufficient numbers of Welsh clubs to run a separate Welsh League section of the competition, alongside the Northern Union's Yorkshire and Lancashire Leagues. The Welsh League lasted only two seasons before folding in 1910 after most of the competing teams disbanded.

The first golden era 1900-1919

The first 'Golden Era' of Welsh rugby is so called due to the success achieved by the national team during the early 20th century. Wales had already won the Triple Crown in 1893, but between 1900 and 1914 the team would win the trophy on six occasions, and with France joining the tournament (unofficially in 1908 and 1909) three Grand Slams.[11]

With the introduction of specialised players like hooker George Travers,[12] the WFU could no longer choose the 'best players' to represent Wales, they needed to think tactically and choose people who could do a specific job on the pitch. This period of Welsh rugby would see the grip of the 'Big Four' clubs providing the bulk of national players, slip slightly. The WFU still tended to turn to the likes of Swansea and Newport to supply the skillful back players and usually kept club half-back pairings together such as Jones and Owen of Swansea. But it was the introduction of the 'Rhondda Forward' which saw men who worked day in day out in the coal, iron and tin mines enter the Welsh front row.[13] Chosen for their strength and aggressive tackling, players such as Dai 'Tarw' Jones from Treherbert and Dai Evans from Penygraig added muscle to the front row.

Although a progressive time for international rugby, this period initially saw regression for many of the club sides in the form of the temperance movement. In the early 1900s, rugby was seen as a wicked temptation to the young men of the mining and steel communities, leading to violence and drink,[14] and the valley areas in particular were part of a strong Nonconformist Baptist movement. The religious revival saw some communities completely reject rugby and local clubs, like Senghenydd, disbanded for several years. It wasn't until the 1910s that the social view of rugby would change the other way, fostered by mine owners as a great social unifier;[15] and like baseball in America would be portrayed as a '...source of community integration because it installed civic pride'.[16]

Unlike the game in England, rugby union in Wales was never seen as a sport for gentlemen of higher learning. Although this was fostered in the first international Welsh team, the fast absorption of the sport into the working class areas appeared to sever the link of rugby as a sport for the middle and upper classes.[17]

As rugby became linked with the hard working men of the industrialised areas of Wales, the sport did not escape the hardships of the industries. In 1913 five members of the Senghenydd team were killed in Britain's worst colliery disaster and many more lost their lives in the 'slow drip' of deaths caused by the industries. Far worse was to follow during the conflict of World War I when many teams lost members, including Welsh internationals like Charlie Pritchard[18] and Johnnie Williams.[19]

Post-war Welsh rugby 1920-1930

The 1920s were a difficult time for Welsh rugby. The first golden period was over and the players that made up the teams that won four Triple Crowns had already disbanded before the Great War. The war could not be blamed for the downturn in Welsh fortunes as all the home nations lost their young talent in equal numbers. The fact that so many of Wales' talented stars had retired from rugby before 1910 was felt when Wales failed to win the tournament in the few years leading up to the war. But the main reason for Welsh failure on the rugby pitch can be mapped to an economic failures of Wales as a country. The First World War had created an unrealistic demand for coal, and in the 1920s the collapse in the need for coal resulted in a massive level of unemployment throughout the south Wales valleys.[20] This in turn led to mass emigration as people left Wales for work. The knock-on effect was felt in the port cities of Newport and Cardiff, that relied on the transportation of coal.

Suddenly the call of the professional league was a very strong draw to men who could not claim money for playing union. Between 1919 and 1939, Forty-eight capped Welsh rugby union players joined league rugby.[21] The fact that the equivalent of three full national squads left the sport can only allude to the number of trialists and club members that also left the sport. Exceptional players lost to the league game included Jim Sullivan of Cardiff, William Absalom of Abercarn and Emlyn Jenkins of Treorchy.[21]

The other side of the depression was linked to those people that stayed behind. In homes where men were the only earners, the decline in heavy labour areas resulted in very stark choices in where the household money could be spent. It was difficult to justify paying to watch rugby when there was little money for food and rent. With crowds dwindling clubs were forced to drastic measures in the hope of survival. Loughor which had produced five internationals in the 1920s were by 1929 begging door to door for old kit.[22] Haverfordwest disbanded from 1926–29, Pembroke Dock Quins were reduced to 5 members by 1927 and in the valleys the Treherbert, Llwynypia and Nantyffyllon clubs had vanished before 1930.[22][23] Even clubs of the size of Pontypool were not spared; in 1927 they were playing and beating the Waratahs and the Maoris, by 1930 they were £2,000 in debt and facing bankruptcy.[24]

Another reason for the fall in the Welsh union game can be placed on the improvement of football in Wales.[25] Traditionally seen as a game more associated with North Wales, the success of Cardiff Football Club in the 1920s was a strong draw for many supporters. With two F.A. Cup Finals in 1925 and 1927, Cardiff were making the once unpopular sport of 'soccer' very fashionable, for fans and sportsmen alike.[20]

During the 1920s the one team that appeared to be unaffected by the double threat of soccer and debt was Llanelli.[26] The Scarlets had an unswerving loyalty shown by their home supporters, who were repaid by exciting, high scoring matches.[26] During the 1925/26 season the club were unbeaten and the next season they had achieved the unprecedented feat of defeating Cardiff on four occasions. This success would later be reflected in the growing number of Llanelli players that would represent their country in the 1920s,[27] including Albert Jenkins, Ivor Jones and Archie Skym.

Apart from a few sporadic victories from the national team, there appeared little to cheer about in the 1920s for Welsh rugby at club or country level; but the seeds of recovery were being planted during the same decade. On 9 June 1923 the Welsh Secondary Schools Rugby Union was established in Cardiff.[28] Founded by Dr R Chalke, head of Porth Secondary School with WRU members Horace Lyne as president and Eric Evans as secretary.[28] Its aim was to promote rugby at school level in an attempt to regain 'the glorious days of Gwyn Nicholls, Willie Llewellyn and Dr E.T. Morgan'. In April 1923, at the Arms Park, Wales played their first secondary schools fixture led by future international Watcyn Thomas, who would progress to captain the first Welsh University XV in 1926.[29] Over the coming years, schools such as Cardiff High School, Llanelli County School, Llandovery and Christ College, Brecon fostered a generation of players which would fill the Welsh ranks over the coming years. Wales had in effect begun to mimic the systems adopted by England and Scotland, that rugby should be nurtured from youth, through adolescence to adulthood.[30]

The 1920s closed with the formation of the West Wales Rugby Union, an event that initially appeared to be a positive indication of growth, but in fact the union was formed by western clubs to wrest control away from the WRU. The West Wales clubs had become disenchanted in decisions made by their parent body and believed the Union had no interest in the lower tier clubs, allowing them to become mere feeders for the bigger clubs.[31]

The Welsh revival 1930-1939

The 1930s began on a high for Welsh international rugby, with success in the Home Nations Championship and the emergence of a strong Welsh team. In the 1931 Championship Wales beat Ireland at Ravenhill in a bruising affair that not only gave Wales the title but denied Ireland the Triple Crown. This may have signaled a change in fortunes in Welsh rugby but underneath the same problems that dogged Wales throughout the 1920s still remained. Wales was still suffering the effects of the depression and club rugby was struggling to survive.[32] Even the WRU had problems, as it faced the fact that it was the only home union without their own ground. The Cardiff Arms was leased and St Helens was on loan.[33] In 1934 nine clubs formed the Welsh Rugby Union with the consent of the WFU.[34]

From what at first appears to be yet another decade of turmoil for Welsh rugby, is actually regarded as a period of revival. The economic situation began turning from 1937, the WSSRU was bringing many exciting backs through the school system, North Wales embraced the game and the national team won two morale lifting games against England in 1933 and the All Blacks in 1935.

From a statistical point of view, the Welsh national team appeared to be winning roughly the same number of games throughout the 1930s as the poor 1920s period, but Wales were actually improving. In the 1920s most Welsh victories were against France, then the weakest team in the Five Nations Championship; but in 1931 France were excluded from the tournament over accusations of professionalism at club level and were not readmitted until after the 1939 tournament, just before international rugby was suspended because of the Second World War. Welsh victories were now coming against the more established home nation teams. During this period, Wales won three Championships, but its greatest victory happened during the 1933 tournament when they finished last. Since its first international game in 1910, Wales had failed to beat England at Twickenham in nine attempts. Now dubbed the 'Twickenham bogey', it took the self-confidence of Cardiff's Ronnie Boon to break the losing streak as he scored a try and a drop goal to take the match 7-3. The game also saw the debut of two players who would become Welsh greats, Wilf Wooller and Vivian Jenkins.

Wales played host to two touring Southern Hemisphere teams in the 1930s, first came Bennie Osler's South Africa followed by Jack Manchester's All Blacks. The South Africans were rampant in Wales, winning the test match and all six club matches, though gained few supporters due to the kicking tactics Osler employed. The New Zealander's received a better welcome, and after the previous tour where the tourist went unbeaten the Welsh press were hoping for a return of the spirit that won the first encounter in 1905. Before the match with Wales, New Zealand were to face eight club teams over six games. After winning the opening three English county matches and then beating a joint Abertillery and Cross Keys the All Blacks were showing the same form shown in their first two tours, but then stumbled against Swansea. Swansea were not in a period of particular growth and the only two players showing any flair were Wales Schoolboy players Willie Davies and Haydn Tanner. During the game Merv Corner could not contain the attacking bursts from Tanner, the New Zealand flankers were drawn in which in turned allowed Davies the freedom to run which Claude Davey finished off with two tries. Jack Manchester's response to the Swansea win was to ask the New Zealand press "Tell them we have been beaten, but don't tell them it was by a pair of schoolboys". This win gave Swansea the honour of being the first club team to have beaten all three major Southern Hemisphere touring teams. The All Blacks were unbeaten in the next twenty matches, but lost to Wales in a classic game which Wales managed to win in the last ten minutes of the game after the Welsh hooker, Don Tarr, was stretchered off with a broken neck.

Post-war Welsh rugby 1945-1959

The post-war years saw strong club teams emerge, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that a true blend of players could be produced to translate club success into international victories. The coming of television saw an upsurge in popularity for the national team, but a decline in club support. Success was gained in the Five Nations Championship, Wales supplied many players to the ranks of the British Lions and New Zealand was beaten for the last time that century.

The decades following on from the Second World War were a boom time for Welsh rugby, though it took until the 1950s for the benefits to be seen on the playing fields. Although Britain was suffering from a post-war slump, attendance figures at club grounds saw an increase as rugby was again embraced as a spectator sport.[35] Towns and villages which had seen their club disbanded during wartime saw their teams re-established. The WRU had 104 member clubs during the 1946-47 season; by the mid fifties there were 130, even though the Union had done nothing to relax its strict membership regulations.[35]

By the 1950s Britain and Wales were beginning to benefit from improved economic conditions. This saw growth in consumer power and spending, which drew many people away from traditional spectator past times, such as sport and the cinema. With a newfound wealth the populace began switching from social pursuits to home entertainment, with the biggest draw being the availability of television. From the mid-fifties there was a significant drop in gate receipts as television became more and more popular. During the 1955 Five Nations Championship, the Scotland v. Wales match was televised live; at the same time an Aberavon v. Abertillery game which would normally draw a crowd of 4000 was unable to muster 400. This created a situation whereby rugby in Wales was gaining in popularity due to the number of people who could now watch the international matches, but support at club level declined.[35] This forced club committees to adopt different strategies to keep their clubs afloat. Many teams set up 'coupon funds' to allow clothing rations to be contributed by members to buy kit. With careful management and thrift most clubs not only survived but grew. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, with little money, many clubs were able to build new facilities or even own their grounds and club-houses for the first time in their history.[36] In 1951 Glamorgan Wanderers purchased the Memorial Grounds in Ely and in 1952 Llanelli were able to purchase the rugby portion of Stradey Park. Similarly, 1954 saw Blaina construct a new stand while Llanharan were able to build their first changing rooms procured from RAF surplus units. These events were typical of club expansion through the 50s. It was around this time that club social activities were extended including the introduction of ladies’ committees.[36]

Clubs also took matters into their own hands to promote themselves and their sport. 1947 saw the first unofficial club championship, won by Neath in its inaugural year, but dominated by Cardiff and Ebbw Vale until the 1960/61 season. In 1954 Welsh rugby sevens had their own tournament with the introduction of the Snelling Sevens competition, while Glamorgan County RFC introduced the Silver Ball Trophy in 1956 for the promotion of second tier clubs in the region.

The national team, after unconvincing displays during the 1940s, found unexpected success in the early 1950s winning the Grand Slam twice; in 1950 and 1952. The 1950 win came after a disastrous 1949 campaign, which saw Wales collect the wooden spoon; but after an opening win over England, the team finished the last three matches conceding only three points. The tournament saw the emergence of Welsh record breaking player Ken Jones as a world class wing; who is most remembered for his late try against the 1953 touring New Zealand team. The 1950 championship is also remembered for the tragic events following the away win to Ireland when a chartered flight, returning from the Triple Crown winning match, crashed at Llandow. Seventy five Welsh fans and five crew died in the accident, at the time it was the world's worst air disaster.[37]

The second golden era 1969-1979

The zenith of Welsh rugby was the 1970s, when Wales had players such as Barry John, Gareth Edwards, Phil Bennett and JPR Williams. Wales won four consecutive Triple Crowns. All of these players are considered amongst the best players of Welsh rugby, especially Edwards who was voted the greatest player of all time in a players poll in 2003 and scored what is widely regarded as the greatest try of all time in 1973 for the Barbarians against New Zealand.

Many attributed Welsh success to the fact that their forwards were toughened by manual work, according to the theory when Welsh industry declined and players started to be drawn from 'soft jobs' the team suffered. The strong Pontypool front row of Graham Price, Bobby Windsor & Charlie Faulkner were all manual workers, and Robin McBryde was formerly the holder of the title of Wales's strongest man.

Shamateurism and the professional era: 1980 to date

See also: Introduction of regional rugby union teams in Wales

The 1980s and early '90s were a difficult time for Welsh rugby union when the team suffered many defeats. Harsh economic times in the eighties meant that players such as Jonathan Davies and Scott Gibbs were tempted to 'go North' to play professional rugby league in order to earn a living.

In 2003/4 the Welsh Rugby Union voted to create five regions to play in the Celtic League (now the RaboDirect Pro12) and represent Wales in European competition. This soon became four when the Celtic Warriors were liquidated after just one season.[38] The WRU have announced their hopes of developing a fifth region in North Wales in the long run; the team at the centre of this plan is now known as RGC 1404.[39]

References

- Smith (1980), pg18.

- Collins, Tony; Martin, John; Vamplew, Wray (2005). Encyclopedia of traditional British rural sports. Sports reference. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0-415-35224-X. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- http://www.rugbyfootballhistory.com/originsofrugby.htm

- Smith (1980), pg22.

- Thomas, Wayne 'A Century of Welsh Rugby Players, 1880-1980'; Ansells Ltd. (1979)

- Smith (1980), pg11.

- Smith (1980), pg11-12.

- Smith (1980), pg14.

- Smith (1980), pg41.

- Smith (1980), pg40.

- Smith (1980), pg481.

- Thomas (1979), pg40.

- David Parry-Jones (1999). Prince Gwyn, Gwyn Nicholls and the First Golden Era of Welsh Rugby (1999) pp. 36. seren.

- Smith (1980), pg120.

- Smith (1980), pg121.

- Morgan (1988), pg391.

- Smith (1980), pg195.

- Thomas (1979), pg43.

- Brendan Gallagher (2008-01-29). "A century since Wales first won Grand Slam". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- Smith (1980), pg224.

- Smith (1980), pg225.

- Smith (1980), pg259.

- Morgan (1988), pg394.

- Smith (1980), pg260.

- Smith (1980), pg232.

- Smith (1980), pg234.

- Smith (1980), pg236.

- Smith (1980), pg240.

- Smith (1980), pg241.

- Smith (1980), pg243-44.

- Smith (1980), pg261.

- Smith (1980), pg268.

- Smith (1984), pg182.

- Smith (1980), pg271.

- Smith (1980), pg330.

- Smith (1980), pg331.

- John Davies, Nigel Jenkins, Menna Baines and Peredur Lynch The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales (2008) pp816 ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6

- "WRU axe falls on Warriors". bbc.co.uk. 2004-07-01. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- "WRU plan for northern development team". The Independent. London. 2008-09-09. Retrieved 2010-05-23.