History of molecular theory

In chemistry, the history of molecular theory traces the origins of the concept or idea of the existence of strong chemical bonds between two or more atoms.

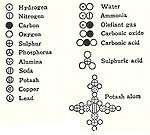

The modern concept of molecules can be traced back towards pre-scientific and Greek philosophers such as Leucippus and Democritus who argued that all the universe is composed of atoms and voids. Circa 450 BC Empedocles imagined fundamental elements (fire (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

17th century

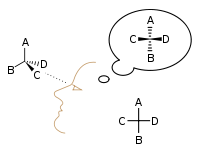

The earliest views on the shapes and connectivity of atoms was that proposed by Leucippus, Democritus, and Epicurus who reasoned that the solidness of the material corresponded to the shape of the atoms involved. Thus, iron atoms are solid and strong with hooks that lock them into a solid; water atoms are smooth and slippery; salt atoms, because of their taste, are sharp and pointed; and air atoms are light and whirling, pervading all other materials.[3] It was Democritus that was the main proponent of this view. Using analogies based on the experiences of the senses, he gave a picture or an image of an atom in which atoms were distinguished from each other by their shape, their size, and the arrangement of their parts. Moreover, connections were explained by material links in which single atoms were supplied with attachments: some with hooks and eyes others with balls and sockets (see diagram).[4]

With the rise of scholasticism and the decline of the Roman Empire, the atomic theory was abandoned for many ages in favor of the various four element theories and later alchemical theories. The 17th century, however, saw a resurgence in the atomic theory primarily through the works of Gassendi, and Newton. Among other scientists of that time Gassendi deeply studied ancient history, wrote major works about Epicurus natural philosophy and was a persuasive propagandist of it. He reasoned that to account for the size and shape of atoms moving in a void could account for the properties of matter. Heat was due to small, round atoms; cold, to pyramidal atoms with sharp points, which accounted for the pricking sensation of severe cold; and solids were held together by interlacing hooks.[5] Newton, though he acknowledged the various atom attachment theories in vogue at the time, i.e. "hooked atoms", "glued atoms" (bodies at rest), and the "stick together by conspiring motions" theory, rather believed, as famously stated in "Query 31" of his 1704 Opticks, that particles attract one another by some force, which "in immediate contact is extremely strong, at small distances performs the chemical operations, and reaches not far from particles with any sensible effect." [6]

In a more concrete manner, however, the concept of aggregates or units of bonded atoms, i.e. "molecules", traces its origins to Robert Boyle's 1661 hypothesis, in his famous treatise The Sceptical Chymist, that matter is composed of clusters of particles and that chemical change results from the rearrangement of the clusters. Boyle argued that matter's basic elements consisted of various sorts and sizes of particles, called "corpuscles", which were capable of arranging themselves into groups.

In 1680, using the corpuscular theory as a basis, French chemist Nicolas Lemery stipulated that the acidity of any substance consisted in its pointed particles, while alkalis were endowed with pores of various sizes.[7] A molecule, according to this view, consisted of corpuscles united through a geometric locking of points and pores.

18th century

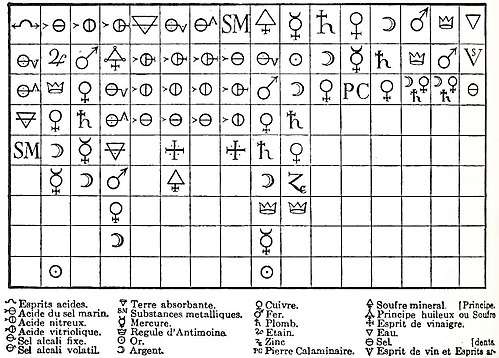

An early precursor to the idea of bonded "combinations of atoms", was the theory of "combination via chemical affinity". For example, in 1718, building on Boyle's conception of combinations of clusters, the French chemist Étienne François Geoffroy developed theories of chemical affinity to explain combinations of particles, reasoning that a certain alchemical "force" draws certain alchemical components together. Geoffroy's name is best known in connection with his tables of "affinities" (tables des rapports), which he presented to the French Academy in 1718 and 1720.

These were lists, prepared by collating observations on the actions of substances one upon another, showing the varying degrees of affinity exhibited by analogous bodies for different reagents. These tables retained their vogue for the rest of the century, until displaced by the profounder conceptions introduced by CL Berthollet.

In 1738, Swiss physicist and mathematician Daniel Bernoulli published Hydrodynamica, which laid the basis for the kinetic theory of gases. In this work, Bernoulli positioned the argument, still used to this day, that gases consist of great numbers of molecules moving in all directions, that their impact on a surface causes the gas pressure that we feel, and that what we experience as heat is simply the kinetic energy of their motion. The theory was not immediately accepted, in part because conservation of energy had not yet been established, and it was not obvious to physicists how the collisions between molecules could be perfectly elastic.

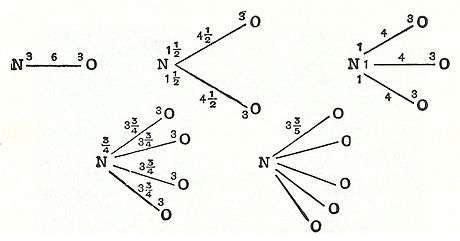

In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of "ultimate" particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds. If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and similarly for the other combinations of ultimate particles:

19th century

Similar to these views, in 1803 John Dalton took the atomic weight of hydrogen, the lightest element, as unity, and determined, for example, that the ratio for nitrous anhydride was 2 to 3 which gives the formula N2O3. Dalton incorrectly imagined that atoms "hooked" together to form molecules. Later, in 1808, Dalton published his famous diagram of combined "atoms":

Amedeo Avogadro created the word "molecule".[8] His 1811 paper "Essay on Determining the Relative Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies", he essentially states, i.e. according to Partington's A Short History of Chemistry, that:[9]

The smallest particles of gases are not necessarily simple atoms, but are made up of a certain number of these atoms united by attraction to form a single molecule.

Note that this quote is not a literal translation. Avogadro uses the name "molecule" for both atoms and molecules. Specifically, he uses the name "elementary molecule" when referring to atoms and to complicate the matter also speaks of "compound molecules" and "composite molecules".

During his stay in Vercelli, Avogadro wrote a concise note (memoria) in which he declared the hypothesis of what we now call Avogadro's law: equal volumes of gases, at the same temperature and pressure, contain the same number of molecules. This law implies that the relationship occurring between the weights of same volumes of different gases, at the same temperature and pressure, corresponds to the relationship between respective molecular weights. Hence, relative molecular masses could now be calculated from the masses of gas samples.

Avogadro developed this hypothesis in order to reconcile Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac's 1808 law on volumes and combining gases with Dalton's 1803 atomic theory. The greatest difficulty Avogadro had to resolve was the huge confusion at that time regarding atoms and molecules—one of the most important contributions of Avogadro's work was clearly distinguishing one from the other, admitting that simple particles too could be composed of molecules, and that these are composed of atoms. Dalton, by contrast, did not consider this possibility. Curiously, Avogadro considers only molecules containing even numbers of atoms; he does not say why odd numbers are left out.

In 1826, building on the work of Avogadro, the French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas states:

Gases in similar circumstances are composed of molecules or atoms placed at the same distance, which is the same as saying that they contain the same number in the same volume.

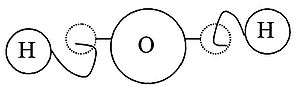

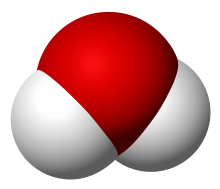

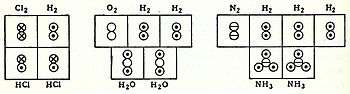

In coordination with these concepts, in 1833 the French chemist Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin presented a clear account of Avogadro's hypothesis,[10] regarding atomic weights, by making use of "volume diagrams", which clearly show both semi-correct molecular geometries, such as a linear water molecule, and correct molecular formulas, such as H2O:

In two papers outlining his "theory of atomicity of the elements" (1857–58), Friedrich August Kekulé was the first to offer a theory of how every atom in an organic molecule was bonded to every other atom. He proposed that carbon atoms were tetravalent, and could bond to themselves to form the carbon skeletons of organic molecules.

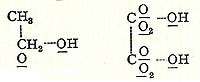

In 1856, Scottish chemist Archibald Couper began research on the bromination of benzene at the laboratory of Charles Wurtz in Paris.[11] One month after Kekulé's second paper appeared, Couper's independent and largely identical theory of molecular structure was published. He offered a very concrete idea of molecular structure, proposing that atoms joined to each other like modern-day Tinkertoys in specific three-dimensional structures. Couper was the first to use lines between atoms, in conjunction with the older method of using brackets, to represent bonds, and also postulated straight chains of atoms as the structures of some molecules, ring-shaped molecules of others, such as in tartaric acid and cyanuric acid.[12] In later publications, Couper's bonds were represented using straight dotted lines (although it is not known if this is the typesetter's preference) such as with alcohol and oxalic acid below:

In 1861, an unknown Vienna high-school teacher named Joseph Loschmidt published, at his own expense, a booklet entitled Chemische Studien I, containing pioneering molecular images which showed both "ringed" structures as well as double-bonded structures, such as:[13]

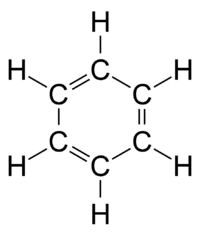

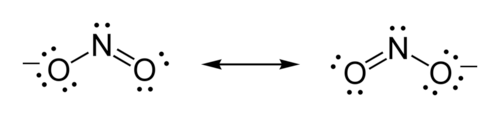

Loschmidt also suggested a possible formula for benzene, but left the issue open. The first proposal of the modern structure for benzene was due to Kekulé, in 1865. The cyclic nature of benzene was finally confirmed by the crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale. Benzene presents a special problem in that, to account for all the bonds, there must be alternating double carbon bonds:

In 1865, German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann was the first to make stick-and-ball molecular models, which he used in lecture at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, such as methane shown below:

The basis of this model followed the earlier 1855 suggestion by his colleague William Odling that carbon is tetravalent. Hofmann's color scheme, to note, is still used to this day: nitrogen = blue, oxygen = red, chlorine = green, sulfur = yellow, hydrogen = white.[14] The deficiencies in Hofmann's model were essentially geometric: carbon bonding was shown as planar, rather than tetrahedral, and the atoms were out of proportion, e.g. carbon was smaller in size than the hydrogen.

In 1864, Scottish organic chemist Alexander Crum Brown began to draw pictures of molecules, in which he enclosed the symbols for atoms in circles, and used broken lines to connect the atoms together in a way that satisfied each atom's valence.

The year 1873, by many accounts, was a seminal point in the history of the development of the concept of the "molecule". In this year, the renowned Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell published his famous thirteen page article 'Molecules' in the September issue of Nature.[15] In the opening section to this article, Maxwell clearly states:

An atom is a body which cannot be cut in two; a molecule is the smallest possible portion of a particular substance.

After speaking about the atomic theory of Democritus, Maxwell goes on to tell us that the word 'molecule' is a modern word. He states, "it does not occur in Johnson's Dictionary. The ideas it embodies are those belonging to modern chemistry." We are told that an 'atom' is a material point, invested and surrounded by 'potential forces' and that when 'flying molecules' strike against a solid body in constant succession it causes what is called pressure of air and other gases. At this point, however, Maxwell notes that no one has ever seen or handled a molecule.

In 1874, Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel independently proposed that the phenomenon of optical activity could be explained by assuming that the chemical bonds between carbon atoms and their neighbors were directed towards the corners of a regular tetrahedron. This led to a better understanding of the three-dimensional nature of molecules.

Emil Fischer developed the Fischer projection technique for viewing 3-D molecules on a 2-D sheet of paper:

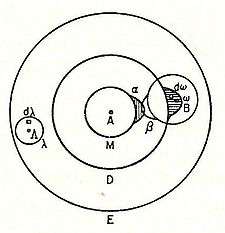

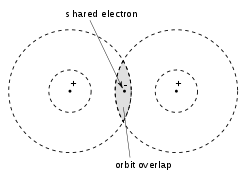

In 1898, Ludwig Boltzmann, in his Lectures on Gas Theory, used the theory of valence to explain the phenomenon of gas phase molecular dissociation, and in doing so drew one of the first rudimentary yet detailed atomic orbital overlap drawings. Noting first the known fact that molecular iodine vapor dissociates into atoms at higher temperatures, Boltzmann states that we must explain the existence of molecules composed of two atoms, the "double atom" as Boltzmann calls it, by an attractive force acting between the two atoms. Boltzmann states that this chemical attraction, owing to certain facts of chemical valence, must be associated with a relatively small region on the surface of the atom called the sensitive region.

Boltzmann states that this "sensitive region" will lie on the surface of the atom, or may partially lie inside the atom, and will firmly be connected to it. Specifically, he states "only when two atoms are situated so that their sensitive regions are in contact, or partly overlap, will there be a chemical attraction between them. We then say that they are chemically bound to each other." This picture is detailed below, showing the α-sensitive region of atom-A overlapping with the β-sensitive region of atom-B:[16]

20th century

In the early 20th century, the American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis began to use dots in lecture, while teaching undergraduates at Harvard, to represent the electrons around atoms. His students favored these drawings, which stimulated him in this direction. From these lectures, Lewis noted that elements with a certain number of electrons seemed to have a special stability. This phenomenon was pointed out by the German chemist Richard Abegg in 1904, to which Lewis referred to as "Abegg's law of valence" (now generally known as Abegg's rule). To Lewis it appeared that once a core of eight electrons has formed around a nucleus, the layer is filled, and a new layer is started. Lewis also noted that various ions with eight electrons also seemed to have a special stability. On these views, he proposed the rule of eight or octet rule: Ions or atoms with a filled layer of eight electrons have a special stability.[17]

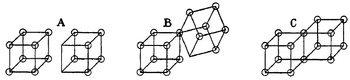

Moreover, noting that a cube has eight corners Lewis envisioned an atom as having eight sides available for electrons, like the corner of a cube. Subsequently, in 1902 he devised a conception in which cubic atoms can bond on their sides to form cubic-structured molecules.

In other words, electron-pair bonds are formed when two atoms share an edge, as in structure C below. This results in the sharing of two electrons. Similarly, charged ionic-bonds are formed by the transfer of an electron from one cube to another, without sharing an edge A. An intermediate state B where only one corner is shared was also postulated by Lewis.

Hence, double bonds are formed by sharing a face between two cubic atoms. This results in the sharing of four electrons.

In 1913, while working as the chair of the department of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, Lewis read a preliminary outline of paper by an English graduate student, Alfred Lauck Parson, who was visiting Berkeley for a year. In this paper, Parson suggested that the electron is not merely an electric charge but is also a small magnet (or "magneton" as he called it) and furthermore that a chemical bond results from two electrons being shared between two atoms.[18] This, according to Lewis, meant that bonding occurred when two electrons formed a shared edge between two complete cubes.

On these views, in his famous 1916 article The Atom and the Molecule, Lewis introduced the "Lewis structure" to represent atoms and molecules, where dots represent electrons and lines represent covalent bonds. In this article, he developed the concept of the electron-pair bond, in which two atoms may share one to six electrons, thus forming the single electron bond, a single bond, a double bond, or a triple bond.

In Lewis' own words:

An electron may form a part of the shell of two different atoms and cannot be said to belong to either one exclusively.

Moreover, he proposed that an atom tended to form an ion by gaining or losing the number of electrons needed to complete a cube. Thus, Lewis structures show each atom in the structure of the molecule using its chemical symbol. Lines are drawn between atoms that are bonded to one another; occasionally, pairs of dots are used instead of lines. Excess electrons that form lone pairs are represented as pair of dots, and are placed next to the atoms on which they reside:

To summarize his views on his new bonding model, Lewis states:[19]

Two atoms may conform to the rule of eight, or the octet rule, not only by the transfer of electrons from one atom to another, but also by sharing one or more pairs of electrons...Two electrons thus coupled together, when lying between two atomic centers, and held jointly in the shells of the two atoms, I have considered to be the chemical bond. We thus have a concrete picture of that physical entity, that "hook and eye" which is part of the creed of the organic chemist.

The following year, in 1917, an unknown American undergraduate chemical engineer named Linus Pauling was learning the Dalton hook-and-eye bonding method at the Oregon Agricultural College, which was the vogue description of bonds between atoms at the time. Each atom had a certain number of hooks that allowed it to attach to other atoms, and a certain number of eyes that allowed other atoms to attach to it. A chemical bond resulted when a hook and eye connected. Pauling, however, wasn't satisfied with this archaic method and looked to the newly emerging field of quantum physics for a new method.

In 1927, the physicists Fritz London and Walter Heitler applied the new quantum mechanics to the deal with the saturable, nondynamic forces of attraction and repulsion, i.e., exchange forces, of the hydrogen molecule. Their valence bond treatment of this problem, in their joint paper,[20] was a landmark in that it brought chemistry under quantum mechanics. Their work was an influence on Pauling, who had just received his doctorate and visited Heitler and London in Zürich on a Guggenheim Fellowship.

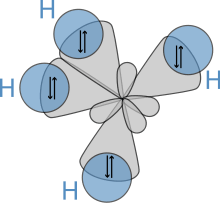

Subsequently, in 1931, building on the work of Heitler and London and on theories found in Lewis' famous article, Pauling published his ground-breaking article "The Nature of the Chemical Bond"[21] (see: manuscript) in which he used quantum mechanics to calculate properties and structures of molecules, such as angles between bonds and rotation about bonds. On these concepts, Pauling developed hybridization theory to account for bonds in molecules such as CH4, in which four sp³ hybridised orbitals are overlapped by hydrogen's 1s orbital, yielding four sigma (σ) bonds. The four bonds are of the same length and strength, which yields a molecular structure as shown below:

Owing to these exceptional theories, Pauling won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Notably he has been the only person to ever win two unshared Nobel prizes, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1963.

In 1926, French physicist Jean Perrin received the Nobel Prize in physics for proving, conclusively, the existence of molecules. He did this by calculating Avogadro's number using three different methods, all involving liquid phase systems. First, he used a gamboge soap-like emulsion, second by doing experimental work on Brownian motion, and third by confirming Einstein's theory of particle rotation in the liquid phase.[22]

In 1937, chemist K.L. Wolf introduced the concept of supermolecules (Übermoleküle) to describe hydrogen bonding in acetic acid dimers. This would eventually lead to the area of supermolecular chemistry, which is the study of non-covalent bonding.

In 1951, physicist Erwin Wilhelm Müller invents the field ion microscope and is the first to see atoms, e.g. bonded atomic arrangements at the tip of a metal point.

In 1999, researchers from the University of Vienna reported results from experiments on wave-particle duality for C60 molecules.[23] The data published by Zeilinger et al. were consistent with de Broglie wave interference for C60 molecules. This experiment was noted for extending the applicability of wave–particle duality by about one order of magnitude in the macroscopic direction.[24]

In 2009, researchers from IBM managed to take the first picture of a real molecule.[25] Using an atomic force microscope every single atom and bond of a pentacene molecule could be imaged.

See also

References

- Russell, Bertrand (2007). A History of Western Philosophy. Simon & Schuster. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4165-5477-6.

- Russell, Bertrand (2007). A History of Western Philosophy. Simon & Schuster. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4165-5477-6.

- Pfeffer, Jeremy, I.; Nir, Shlomo (2001). Modern Physics: An Introduction Text. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 183. ISBN 1-86094-250-4.

- See testimonia DK 68 A 80, DK 68 A 37 and DK 68 A 43. See also Cassirer, Ernst (1953). An Essay on Man: an Introduction to the Philosophy of Human Culture. Doubleday & Co. p. 214. ISBN 0-300-00034-0. ASIN B0007EK5MM.

- Leicester, Henry, M. (1956). The Historical Background of Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 112. ISBN 0-486-61053-5.

- (a) Isaac Newton, (1704). Opticks. (pg. 389). New York: Dover.

(b) Bernard, Pullman; Reisinger, Axel, R. (2001). The Atom in the History of Human Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 0-19-515040-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lemery, Nicolas. (1680). An Appendix to a Course of Chymistry. London, pgs 14-15.

- Ley, Willy (June 1966). "The Re-Designed Solar System". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- Avogadro, Amedeo (1811). "Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies". Journal de Physique. 73: 58–76.

- Seymour H. Mauskopf (1969). "The Atomic Structural Theories of Ampère and Gaudin: Molecular Speculation and Avogadro's Hypothesis". Isis. 60 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1086/350449. JSTOR 229022.

- Chemical Bonding Concepts – Oklahoma State University

- Bowden, Mary Ellen (1997). Chemical achievers : the human face of the chemical sciences. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 90–93. ISBN 9780941901123.

- Bader, A. & Parker, L. (2001). "Joseph Loschmidt", Physics Today, Mar.

- Ollis, W. D. (1972). "Models and molecules". Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. 45: 1–31.

- Maxwell, James Clerk, "Molecules Archived 2007-02-09 at the Wayback Machine". Nature, September, 1873.

- Boltzmann, Ludwig (1898). Lectures on Gas Theory (Reprint ed.). Dover. ISBN 0-486-68455-5.

- Cobb, Cathy (1995). Creations of Fire - Chemistry's Lively History From Alchemy to the Atomic Age. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-7382-0594-X.

- Parson, A.L. (1915). "A Magneton Theory of the Structure of the Atom". Smithsonian Publication 2371, Washington.

- "Valence and The Structure of Atoms and Molecules", G. N. Lewis, American Chemical Society Monograph Series, page 79 and 81.

- Heitler, Walter; London, Fritz (1927). "Wechselwirkung neutraler Atome und homöopolare Bindung nach der Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik. 44: 455–472. Bibcode:1927ZPhy...44..455H. doi:10.1007/BF01397394.

- Pauling, Linus (1931). "The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 53: 1367–1400. doi:10.1021/ja01355a027.

- Perrin, Jean, B. (1926). Discontinuous Structure of Matter, Nobel Lecture, December 11.

- Arndt, M.; O. Nairz; J. Voss-Andreae; C. Keller; G. van der Zouw; A. Zeilinger (14 October 1999). "Wave-particle duality of C60 molecules". Nature. 401 (6754): 680–682. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..680A. doi:10.1038/44348. PMID 18494170.

- Rae, A. I. M. (14 October 1999). "Quantum physics: Waves, particles and fullerenes". Nature. 401 (6754): 651–653. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..651R. doi:10.1038/44294.

- Single molecule's stunning image.

Further reading

- Partington, J.R. (1989). A Short History of Chemistry. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-65977-1.

- Atkins, Peter (2003). Atkins' Molecules, 2nd Ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53536-0.

- Sargent, Ted (2006). The Dance of Molecules - How Nanotechnology is Changing our Lives. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-809-8.

- Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The Periodic Table, Its Story and Its Significance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9.

External links

- Geometric Structures of Molecules - Middlebury College

- Atoms and Molecules - McMaster University

- 3D Molecule Viewer - The Wileys Family

- Molecule of the Month - School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

- - Eric Scerri's history & philosophy of chemistry website

Types

- Antibody Molecule - The National Health Museum

- 15 Types of Molecules - IUPAC Definitions

Definitions

- Molecule Definition - Frostburg State University (Department of Chemistry)

- Definition of Molecule - IUPAC

Articles

- Molecules Used to Make Nano-sized Containers - TRN Newswire

- Molecular Computer Processors - HP Labs