History of Science Museum, Oxford

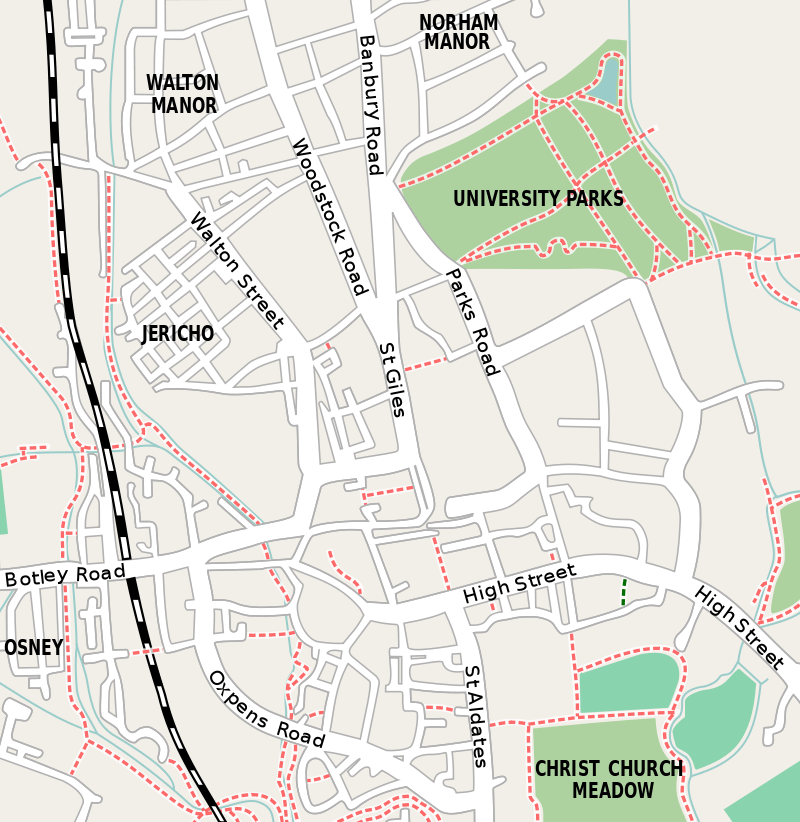

The History of Science Museum in Broad Street, Oxford, England, holds a leading collection of scientific instruments from Middle Ages to the 19th century. The museum building is also known as the Old Ashmolean Building to distinguish it from the newer Ashmolean Museum building completed in 1894. The museum was built in 1683, and it is the world's oldest surviving purpose-built museum.

The Old Ashmolean Building as it stands today | |

History of Science Museum, Oxford | |

| Established | 1683 (as Ashmolean Museum) 1924 (as Museum of the History of Science) |

|---|---|

| Location | Broad Street, Oxford, England |

| Coordinates | 51.75443°N 1.25519°W |

| Type | University museum of the history of science |

| Visitors | 176,757 (2018)[1] |

| Director | Silke Ackermann |

| Website | History of Science Museum |

The museum is open to the general public every afternoon except Mondays, with free admission.

History

Built in 1683 to house Elias Ashmole's collection, it was the world's first purpose-built museum building and was also open to the public. The original concept of the museum was to institutionalize the new learning about nature that appeared in the 17th century and experiments concerning natural philosophy were undertaken in a chemical laboratory in the basement, while lectures and demonstration took place in the School of Natural History, on the middle floor. Ashmole's collection was expanded to include a broad range of activities associated with the history of natural knowledge and in 1924 the gift of Lewis Evans' collection allowed the museum further improvement, becoming the Museum of the History of Science and appointing Robert Gunther as its first curator.

Collections and exhibitions

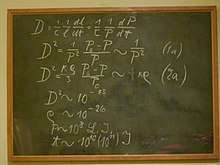

The collection and the building itself now occupies a special position in the study of the history of science and in the development of western culture and collecting. One of the most iconic objects in the collection is Einstein's Blackboard[2] that Albert Einstein used on 16 May 1931 in his lectures while visiting the University of Oxford, rescued by dons including and E. J. Bowen and Gavin de Beer.[3]

The current collection contains around 18,000 objects from antiquity to the early 20th century, representing almost all aspects of the history of science and is used for both academic study and enjoyment by the visiting public. The museum contains a wide range of scientific instruments, such as quadrants, astrolabes (the most complete collection in the world with c.170 instruments), sundials, early mathematical instruments (used for calculating, astronomy, navigation, surveying and drawing), optical instruments (microscopes, telescopes and cameras), equipment associated with chemistry, natural philosophy and medicine, and a reference library regarding the history of scientific instruments that includes manuscripts, incunabula, prints and printed ephemera, and early photographic items.

The museum shows the development of mechanical clocks. Lantern clocks and longcase clocks are exhibited in the Beeson Room, named after the antiquarian horologist Cyril Beeson (1889–1975)[4] who gave his collection to the museum. Early turret clocks are exhibited above the stairs from the basement to the raised ground floor.

From October 2009 until February 2010, the Museum hosted the first major exhibition of Steampunk art objects, curated by Art Donovan and presented by Dr Jim Bennett, then the museum director.[5][6]

The museum is also home to the Rochester Avionic Archive, which includes a collection of avionics that originated with the Elliot Brothers, but also includes pieces from Marconi and BAE Systems.[7]

Curators

The following have been Curator or Secretary to the Committee or Director at the museum:[9][10]

- R. T. Gunther (1924–40)

- F. Sherwood Taylor (1940–45, temporary; 1945–50)

- C. H. Josten (1950–64; 1964–94, emeritus)

- F. R. Maddison (1964–94)

- J. A. Bennett (1994–2012)

- Stephen Johnston (acting director, 2012–14)

- Silke Ackermann (2014 onwards)

See also

- Dr Jim Bennett, the museum's former Keeper/Director (retired in 2012)

- Dr Silke Ackermann, the museum's Director (from 2014)

- Oxford University Scientific Society

- Whipple Museum of the History of Science, the equivalent institution at the University of Cambridge

- Ashmolean Museum

References

- "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Bye-bye blackboard... from Einstein and others". Museum of the History of Science.

- Gunther, A. E. (1967). Robert T. Gunther. Early Science in Oxford. XV. Oxford. pp. 250, 436.

- Beeson, C.F.C. (1989) [1962]. A.V., Simcock (ed.). Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400–1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. frontispiece. ISBN 0-903364-06-9.

- "Steampunk". Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.

Imagine the technology of today with the aesthetic of Victorian science. From redesigned practical items to fantastical contraptions, this exhibition showcases the work of eighteen Steampunk artists from across the globe.

- Ward, Mark (30 November 2009). "Tech Know: Fast forward to the past". Technology. BBC. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- "ABOUT ROCHESTER AVIONIC ARCHIVES". Rochester Avionic Archives. Rochester Avionic Archives. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "Set of Beevers Lipson Strips, Sine Set, c. 1936". Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Simcock, A. V., ed. (1985). Robert T. Gunther and the Old Ashmolean. Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. p. 93. ISBN 0-903364-04-2.

- Fox, Robert (January 2006). "The history of science, medicine and technology at Oxford". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 60 (1): 69–83. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2005.0129. PMID 17153170.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. |