Lantern clock

A lantern clock is a type of antique weight-driven wall clock, shaped like a lantern. They were the first type of clock widely used in private homes.[1] They probably originated before 1500 but only became common after 1600;[1] in Britain around 1620. They became obsolete in the 19th century.

Origin of the name

There are two theories of the origin of the name "lantern clock". One is that it refers to brass, the main metal of which English lantern clocks are made. Clocks were first made on the continent, at first of iron with iron wheels, and then later with brass wheels. Later still, in France, Belgium and The Netherlands, clocks began to be made from brass.[2] Brass alloys were then called latten, and it seems likely that brass clocks would have been called "latten clocks" (or "latten horloge" or "latten uhr" in the native languages) to distinguish them from iron clocks, and that "lantern" could be an English interpretation or corruption of latten. The other is that the name derived from the shape; the clock resembles a rectangular lantern of that period, and like a lantern was hung on the wall.

In inventories of deceased clockmakers, lantern clocks are usually referred to as "house clocks", "chamber clocks" or simply "clocks", since in 17th century England they were almost the only type of domestic clocks that existed. It was only after a century had passed, when other types of domestic clocks began to be used in British houses, that more descriptive names for it appeared. Other names used for lantern clocks are "bedpost", "birdcage" or "Cromwellian" clocks. "Sheep's head clock" was a nickname term for a type of lantern clock that had an extremely large chapter ring covering almost the entire front.

Origin of lantern clocks

The English lantern clock is closely related to lantern clocks that can be found on the European continent. A group of craftsmen from the Low Countries and France, of which some were clockmakers, had established themselves in London at the end of the 16th century. At the same time the middle classes in towns and cities of England began to prosper and the need arose for domestic clocks. Until that time clocks in English houses were confined to the nobility; ordinary people were dependent on sundials, or the tower clocks of local churches.

It is generally accepted that the first lantern clocks in England were made by Frauncoy Nowe and Nicholas Vallin, two Huguenots who had fled from the Low Countries.

Style characteristics

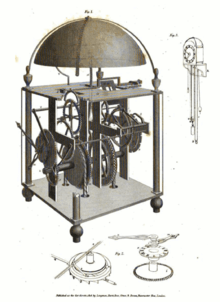

Lantern clocks were made almost entirely of brass, whereas most earlier clocks had been constructed from iron and wood. Typical lantern clocks comprised a square case on ball or urn feet, a large circular dial (with a chapter ring extending beyond the width of the case on early examples), a single hour hand, and a large bell and finial. The clocks usually had ornate pierced fretwork on top of the frame.

The main style characteristics of English lantern clocks are similar to its Continental relatives: a wall clock with square bottom and top plates surmounted by a large bell, four corner pillars, a series of vertical plates positioned behind each other and a 30-hour movement with one or more weights. At the start of the 17th century, the style gradually evolved to a standard to which all clockmakers more or less complied. The guild supervised the clockmakers, who were compelled to work within a prescribed method. Suppliers to the clockmakers' trade contributed to this general style as well. For example, the brass founders supplied stylistically identical clock posts to several clockmakers. In contrast to the Dutch variants, such as stool clocks, English lantern clocks were entirely made of metal (brass and steel).

Lantern clocks were originally weight-driven: usually one weight for time keeping and a second for striking. A few later lantern-style clocks were constructed with spring mechanisms, and many surviving examples of the original weight-driven type have been converted to spring or pendulum mechanisms.

Guild system

In only a few decades the lantern clock became very popular in London, and from there its popularity spread to the entire country. This is evident from the large number of lantern clocks that still exist. Dozens of clockmakers produced great numbers of these clocks in the city of London during the 17th century. This huge productivity was the result of the high demand for this popular clock in combination with an effective guild system. In 1631 King Charles I granted a charter for a clockmaker guild in London: the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, which exists to this day. Many of the well-known clockmakers from that era were freemen of this guild. Many small companies were established in Lothbury in London that functioned as suppliers for the clockmakers. A clockmaker could benefit from the services of brass founders who supplied cast brass clock parts, dial plates, finials, pillars, frets etc., or employ engravers who would carry out the engraving of the dial plates and frets. The guild assured the quality of the products that left the clockmakers' workshops. Before a clockmaker could become a freeman, able to set up his own shop, he had to spend 7 years as an apprentice learning the trade. This ensured independent clockmakers a plentiful supply of apprentices, who were also cheap labourers who helped to attain this high productivity.

Influence of the Renaissance

Style characteristics were copied from prints that were available for craftsmen. Under the influence of the Renaissance, prints with motives and patterns from the Classical antiquity found their way to the workshops. They served as examples for the clock pillars that were inspired by columns from Greek temples. During the 17th century the tulip became very popular to an extent of a real tulip mania. Prints with pictures of tulips were a rewarding subject for the adornment of the dial plates of lantern clocks. In the early 17th century, lantern clocks got their characteristic shape, which hardly changed during the 17th and halfway through the next century as a result of all this.

Clock parts

The London Clockmakers equipped their lantern clocks with four pillars inspired by classical columns. Attached to these pillars are classical vase-shaped finials and well-shaped feet. To those finials a bell strap is attached that spreads from four corners and holds a bell. To hide the hammer and the clock movement from the spectator three frets are attached to the finials. The front fret is pierced and engraved whereas the two side frets are pierced but usually left blank. The front of the clock case consists of an engraved dial plate on which a circular dial ring is attached. Almost all lantern clocks originally had just one clock hand to indicate the hours. A standard lantern clock strikes the hours on a large bell and is often equipped with an alarm that rings the same bell. Two doors provide access to the movement and are hinged at the sides of the clock. One or more weights are hanging from ropes or chains at the bottom of the clock.

Obsolescence

Lantern clocks were produced in vast numbers during the decades before the pioneering invention of the pendulum by the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens in 1656. Before this invention, lantern clocks used a balance wheel lacking a balance spring for their timekeeping element, which limited their accuracy to perhaps 15 minutes per day. Shortly after Huygens' invention, the bob pendulum was introduced in England, and most English clockmakers adopted the new system quickly. The pendulum increased the accuracy of clocks so greatly that many existing clocks were converted, with pendulums being added at the back. Measuring time became much more accurate, but most clockmakers kept building lantern clocks without minute hands: this maybe just a matter of tradition. The result was that clockmakers started to develop other types of domestic clocks. Longcase clocks with 8-day movements made lantern clocks obsolete, and gradually lantern clocks disappeared from the London interiors in the first decades of the 18th century. In rural areas lantern clocks were produced until the beginning of the 19th century, and in those years they were also exported to countries like Turkey, and supplied with oriental numbers on their dials. In the Victorian era there was a revival of interest in antique lantern clocks. Unfortunately this also meant that many clocks of renowned makers were stripped of their movements, which were replaced by 'modern' winding movements. Nowadays unmodified original lantern clocks are very rare.

References

- Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. pp. 89–94. ISBN 0780800087.

- Robey, J.A., "Iron Crossings and Brass Rims", The Horological Journal, British Horological Institute, Newark, England,July 2015

- Hana, W.F. English Lantern Clocks

- White, George English Lantern Clocks

- Jeff Darken & John Hooper English 30 Hour Clocks Penita Books (1997) ISBN 0953074501

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lantern clocks. |