History of Cluj-Napoca

The history of Cluj-Napoca covers the time from the Roman conquest of Dacia, when a Roman settlement named Napoca existed on the location of the later city, through the founding of Cluj and its flourishing as the main cultural and religious center in the historical province of Transylvania, until its modern existence as a city, the seat of Cluj County in north-western Romania.

Ancient times

Etymology and origin

About the origin of the settlement's name Napoca or Napuca several hypotheses have been advanced. The most important are the following:

- Dacian name having the same root "nap" (cf. ancient Armenian root "nap") as that of the Dacian river Naparis attested by Herodotus, but with an augmentative suffix uk/ok i.e. over, great[3]

- Name derived from that of the Dacianized Scythian tribe known as the Napae[4]

- Name probably akin to an indigenous (Thracian) element in Romanian, the word năpârcă 'viper' cf. Albanian nepërkë, nepërtkë[5]

- Name derived from the Ancient Greek term napos (νάπος), meaning "timbered valley"

- Name derived from the Indo-European root *snā-p- (Pokorny 971-2), "to flow, to swim, damp".[6]

Independent of these hypotheses, scholars agree that the name of the settlement predates the Roman conquest (AD 106).[6]

Pre-Roman times

The oldest human settlement near Cluj, dating from the Neolithic Age, is at Gura Baciului, near Suceagu, in the valley of a tributary of the Nadăș river and nearby the Hoia Forest. The settlement dates back to 6000–5500 BCE, making it the oldest in Transylvania. Archaeologists have connected it with the Starčevo–Kőrös–Criş culture, and other similar settlements have been discovered since: a tomb from this same culture in the Mănăștur district, and another settlement on the Strada Memorandumului.

Traces of the Thracian-Dacians and Celts suggest that the region was occupied intermittently throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages. As economies centered around cattle-raising developed in the Pannonian plain, the importance of the salt trade with the Transylvanian Plain became ever more important. Two major routes, one running north–south and the other east–west, met on the right end of a ford under the promontory of a hill, today named Cetățuie. Presumably there was at one time a Dacian fortress controlling this central communication point, which would later have been destroyed in the early 18th century construction of Austrian fortifications.

Roman times

The Romans conquered Dacia between AD 101 and 106 under Trajan, and a Roman settlement of Napoca is first recorded on a milestone found in 1758 in the nearby Aiton commune.[7]

The Milliarium of Aiton is an ancient Roman milestone (milliarium) dating from 108 AD, shortly after the conquest, evidence of the construction of a road from Potaissa to Napoca. It indicates a distance of ten thousand feet (P.M.X.) to Potaissa. This is the first epigraphical attestation of the settlements of Potaissa and Napoca in Roman Dacia.

The complete inscription is: "Imp(erator)/ Caesar Nerva/ Traianus Aug(ustus)/ Germ(anicus) Dacicus/ pontif(ex) maxim(us)/ (sic) pot(estate) XII co(n)s(ul) V/ imp(erator) VI p(ater) p(atriae) fecit/ per coh(ortem) I Fl(aviam) Vlp(iam)/ Hisp(anam) mil(liariam) c(ivium) R(omanorum) eq(uitatam)/ a Potaissa Napo/cam / m(ilia) p(assuum) X". It was recorded in the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, vol.III, the 1627, Berlin, 1863.

This milliarium is evidence of a road known to be built by Cohors I Hispanorum miliaria.[8]

Trajan's successor Hadrian granted the title and rank of municipium to the Roman settlement at Napoca[9] naming it municipium Aelium Hadrianum Napocenses. Later, in the 2nd century AD,[10] the city gained the status of a colonia as Colonia Aurelia Napoca, probably during the reign of Marcus Aurelius.

Napoca became a provincial capital of Dacia Porolissensis and thus the seat of a procurator. The colonia was abandoned in 274 by the Roman administration.[7]

During the Migrations Period Napoca was overrun and destroyed. There are no references to urban settlement on the site for the better part of a millennium thereafter. Villages did spring up on the nearby countryside which displayed continuation in culture from the Roman period, likely populated by settlers that had abandoned the city.[11]

Middle Ages

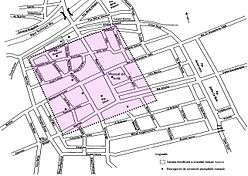

.jpg)

After the departure of the Romans to the southern banks of the Danube in the 3rd century, nothing is certain about the site's history as a settlement until the Hungarians (Magyars) arrived in Pannonia in the 9th Century. The modern city of Cluj-Napoca was founded by German settlers as Klausenburg in the 13th Century. The name "Napoca" was added to the traditional Romanian city name "Cluj" by dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1974 as a means of asserting Romanian claims to the region on the basis of the theory of Daco-Roman Continuity. Although the precise date of the conquest of Transylvania by the Hungarians is not known, the earliest Hungarian artifacts found in the region are dated to the first half of the 10th century.[12] After the conquest, the city became part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

King Stephen I made the city the seat of the castle county of Kolozs, and King Saint Ladislaus I of Hungary founded the abbey of Cluj-Mănăştur (Kolozsmonostor), destroyed during the Tatar invasions in 1241 and 1285.[13] As for the civilian colony, a castle and a village were built to the northwest of the ancient Napoca no later than the late 12th century.[13] This new village was settled by large groups of Transylvanian Saxons, encouraged during the reign of Crown Prince Stephen, Duke of Transylvania.[14]

The first reliable mention of the settlement dates from 1275, in a document of King Ladislaus IV of Hungary, when the village (Villa Kulusvar) was granted to the Bishop of Transylvania.[15] On August 19, 1316, during the rule of the new king, Charles I of Hungary, Cluj was granted the status of a city (Latin: civitas), as a reward for the Saxons' contribution to the defeat of the rebellious Transylvanian voivode, Ladislaus Kán.[15] In memory of this event, the Saint Michael Church started to be built.

In 1331 the voivode of Transylvania lost his supremacy over Kuluzsvar. Kolozsvar-Klausenburg became a royal free city in 1405. By this time the number of Saxon and Hungarian inhabitants was equal, and King Matthias Corvinus (born in Klausenburg in 1440) ordered that the office of the chief judge should alternate between Hungarians and Saxons.

The lovers of Cluj-Napoca are believed to have lived between 1450 and 1550.

Principality of Transylvania

In 1541 Klausenburg became part of the autonomous Principality of Transylvania after the Ottoman Turks occupied the central part of the Hungarian Kingdom. Although Alba Iulia served as political capital for the Principality of Siebenbürgen (Transylvania), Klausenburg was the main cultural and religious center for the principality. In 1581, Stefan Batory, Governor of Transylvania, took the initiative in founding a Jesuit academy in Klausenburg.

Between 1545 and 1570, large numbers of Germans (Saxons) left the city due to the introduction of Unitarian doctrines. The remaining Germans were assimilated to Hungarians, and the city became a centre for Hungarian nobility and intellectuals. With the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, Klausenburg became part of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Austrian Empire and Grand Principality of Transylvania

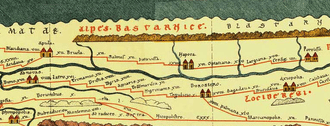

.jpg)

From 1790 to 1848 and again from 1861 to 1867, Klausenburg was the capital of the Grand Principality of Transylvania (Siebenbürgen) within the Austrian Empire; the city was also the seat of the Transylvanian diets. Beginning in 1830, the city became the centre of the Hungarian national movement within the principality. During the Revolutions of 1848, Klausenburg was taken and garrisoned in December by Hungarian troops under the command of the Polish general Józef Bem.

In 1776, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria founded a German university in Cluj. But this enterprise was not to survive long, Emperor Joseph II replacing the university with the famous Piarist Highschool, where the teaching was done in Latin. The first Hungarian-language newspaper was published in Klausenburg in 1791, and the first Hungarian theatrical company was established in 1792. In 1798, the city was heavily damaged by a fire.

For lighting, oil lamps were introduced in 1826, gas lamps in 1861 and electric lights in 1906.[16]

Austro-Hungarian Empire

After the Ausgleich (compromise) which created Austria-Hungary in 1867, Klausenburg and Transylvania were again integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary. During this time, Kolozsvar was among the largest and most important cities of the kingdom, and was the seat of Kolozs County. In 1897, the Hungarian government decided that only Hungarian place names should be used and therefore prohibited the use of the German or Romanian versions of the city's name in official government documents.[17]

In 1872, the authorities established a University in Cluj, with teaching exclusively in Hungarian, which caused discontent amongst the Romanian population. In 1881 the University was renamed Franz Joseph University after Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria.

Twentieth century

After World War I, Cluj became part of the Kingdom of Romania, along with the rest of Transylvania. The Romanian authorities took over the University of Cluj, transforming it into a Romanian institution. On May 12, 1919, the Romanian University of Cluj was set up, with King Ferdinand proclaiming the University open on February 1, 1920.

In 1940 Cluj was returned to Hungary through the Second Vienna Award, but Hungarian forces in the city were defeated by the Soviet and Romanian armies in October 1944. Cluj was restored to Romania by the Treaty of Paris in 1947. The Northern Transylvania People's Tribunal was set up in Cluj by the post-World War II government of Romania, overseen by the Allied Control Commission, to try suspected war criminals. The Cluj Tribunal passed a total of 100 death sentences, 163 sentences of life imprisonment, and a range of other sentences.

Cluj had 16,763 inhabitants of Jewish ancestry in 1941. After the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944, the city's Jews were forced into ghettos under conditions of intense overcrowding and practically no facilities. Liquidation of the ghetto occurred through six deportations to Auschwitz between May and June 1944. Despite facing severe sanctions from the Horthy administration, many Jews escaped across the border to Romania with the assistance of Romanian peasants of neighboring villages. They were then able to flee Europe from the Romanian Black Sea port of Constanţa. Other Jews originating from East European countries were helped to escape from Europe by an Anti-Nazi group led by the Jewish Joint and Romanian politicians in Cluj and Bucharest. The leader of this network, between 1943 and 1944, was Raoul Şorban.

After World War II, the Romanian university (which had moved to Sibiu and Timișoara in the aftermath of the Second Vienna Award) returned to Cluj and took the name "Babeş", after the scientist Victor Babeş. Parts of the Hungarian university moved to Szeged and were later named University of Szeged, which became one of the most distinguished universities in Hungary and in Central Europe. The remaining parts formed the Hungarian University of Cluj and took the name "Bolyai", after the mathematician János Bolyai. The two universities, the Romanian Babeş University and the Hungarian Bolyai University, merged in 1959 forming the Babeş-Bolyai University, with teaching in both Romanian and Hungarian. Nowadays, this is the largest university in Romania.

Hungarians remained the majority of the city's population until the 1960s, when for the first time in its long history, Romanians outnumbered Hungarians. According to the 1966 census, the city's population of 185,663 was composed of 56% Romanians and 41% Hungarians. Until 1974 the official Romanian name of the city was Cluj. It was renamed to Cluj-Napoca by the Communist government to recognize it as the site of the Roman colony Napoca.

After the Romanian revolution

Following the Romanian Revolution of 1989, the nationalist politician Gheorghe Funar became mayor for 12 years. His tenure was marked by strong Romanian nationalistic and anti-Hungarian ideas. A number of public art projects were undertaken by the city with the aim of highlighting Romanian symbols of the city, most of them regarded by Hungarian ethnics as a way of obscuring the city's Hungarian ancestry. In June 2004 Gheorghe Funar was voted out of office. He was replaced by Emil Boc of the Democratic Party. The laws on municipal bilingualism have not been applied in administration as the 2002 city census showed less than 20% Hungarians.

In 1994 and 2000, Cluj-Napoca hosted the Central European Olympiad in Informatics (CEOI). It thus made Romania not only the first country to have hosted the CEOI, but also the first country to have hosted it a second time.

The city is known in Hasidic Jewish history for the founding of the Sanz-Klausenburg dynasty.[18]

In 2015 Cluj was awarded the "European Youth Capital" title.

See also

Footnotes

a.^ The engraving, dating back to 1617, was executed by Georg Houfnagel after the painting of Egidius van der Rye (the original was done in the workshop of Braun and Hagenberg).

Notes

- Tabula Peutingeriana, Segmentum VIII.

- Bunbury 1879, p. 516.

- Tomaschek (1883) 406

- Pârvan (1982) p.165 and p.82

- Paliga (2006) 142

- Lukács 2005, p. 14.

- Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp. 202–3 (6.2 Cluj in the Old and Ancient Epochs)

- ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPERTORY OF ROMANIA. Archive Of The Vasile Parvan Institute Of Archaeology – Site Location Index

- Bennett (2001) 170

- Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 17 (2.7 Napoca romană)

- Diaconescu, A. “The towns of Roman Dacia: an overview of recent research.” ed. Hanson, W. S. and Haynes, I. P. Roman Dacia: the Making of a Provincial Society. Portsmouth, RI, USA : Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2004. p. 133

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2001). Românii în opera Notarului Anonim. Cluj-Napoca: Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Fundația Culturală Română. ISBN 973-577-249-3.

- Lazarovici et al. 1997, p.32 (3.1 De la Napoca romană la Clujul medieval)

- "O istorie inedită a Clujului – Cetatea coloniştilor saşi" (in Romanian). ClujNet.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- Lazarovici et al. 1997, p. 204 (6.3 Medieval Cluj)

- Lazarovici et al. 1997, p.73 (4.1 Centru al mişcării revoluţionare)

- Georges Castellan, A history of the Romanians, Boulder, 1989, pp.148

- Rabinowicz, Tzvi M. (1996). The Encyclopedia of Hasidism. Jason Aronson, Inc. ISBN 1-56821-123-6.

References

Ancient

- Anonymous (1–4th century AD). Tabula Peutingeriana (in Latin). Check date values in:

|year=(help)

Modern

- Bennett Julian (2001). Trajan: optimus princeps. Indiana University Press; 2nd edition. ISBN 0-253-21435-1, ISBN 978-0-253-21435-5.

- Gheorghe Bodea (2002). Clujul vechi şi nou. ProfImage. ISBN 973-0-02539-8.

- Gh. Lazarovici; D. Alicu; C. Pop; I. Hica; P. Iambor; Şt. Matei; E. Glodaru; I. Ciupea; Gh. Bodea (1997). Cluj-Napoca – Inima Transilvaniei. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Studia. ISBN 973-97555-0-X.

- Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1879). A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lukács, József (2005). Povestea "orașului-comoară": Scurtă istorie a Clujului și a monumentelor sale (in Romanian). Apostrof. ISBN 973-9279-74-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paliga Sorin (2006). Etymological Lexicon of the Indigenous (Thracian) Elements in Romanian" / "Lexicon etimologic al elementelor autohtone (traco-dace) ale limbii române". Editura Evenimentul.

- Pârvan Vasile (1982). Getica. Meridiane.

- Raoul Şorban (2003). Invazie de stafii. Însemnări şi mărturisiri despre o altă parte a vieţii. Meridiane. ISBN 973-33-0477-8.

- Tomaschek Wilhelm (1883). "Les Restes de la langue dace" in "Le Muséon, Volume 2". "Société des lettres et des sciences" Louvain, Belgium.

- Judeţul Cluj – trecut şi prezent. ProfImage. 2003. ISBN 973-7924-05-3.

- "Cluj-Napoca, oraşul comoară al Transilvaniei, România". CLUJonline.com. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- "O istorie inedită a Clujului". ReMARK ltd. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- "Anuarul Institutului de Istorie "George Bariţ" din Cluj-Napoca". "George Bariţ" History Institute, Cluj-Napoca / Romanian Academy. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Cluj-Napoca. |