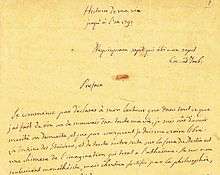

Histoire de ma vie

Histoire de ma vie (Story of My Life) is both the memoir and autobiography of Giacomo Casanova, a famous 18th-century Italian adventurer. A previous, bowdlerized version was originally known in English as The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova (from the French Mémoires de Jacques Casanova) until the original version was published in 1960.

From 1838 to 1960, all the editions of the memoirs were derived from the censored editions produced in German and French in the early nineteenth century. Arthur Machen used one of these inaccurate versions for his English translation published in 1894 which remained the standard English edition for many years.

Although Casanova was Venetian (born 2 April 1725, in Venice, died 4 June 1798, in Dux, Bohemia, now Duchcov, Czech Republic), the book is written in French, which was the dominant language in the upper class at the time. The book covers Casanova's life only through 1774, although the full title of the book is Histoire de ma vie jusqu'à l'an 1797 (History of my Life until the year 1797).

On 18 February 2010, the National Library of France purchased the 3,700-page manuscript[1] of Histoire de ma vie for approximately €7 million (£5,750,000). The manuscript is believed to have been given to Casanova's nephew, Carlo Angiolini, in 1798. The manuscript is believed to contain pages not previously read or published.[2] Following this acquisition, a new edition of the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, based on the manuscript, was published from 2013 to 2015.[3]

Contents of the book

The book comprises 12 volumes and approximately 3,500 pages (1.2 million words) covering Casanova's life from his birth to 1774.

Story of the manuscript

Casanova allegedly wrote the first chapters of the book in 1789, during a profound illness.

In 1794, Casanova met Charles Joseph, Prince de Ligne. The two of them established a mutual friendship. The Prince expressed a desire to read Casanova's memoirs, and Casanova decided to polish the manuscript before sending it to the Prince. After reading at least the first three tomes of the manuscript, Charles Joseph suggested that the memoir be shown to an editor in Dresden to publish in exchange for an annuity. Casanova was convinced to publish the manuscript, but chose another route. In 1797, he asked Marcolini Di Fano, minister at the Cabinet of the Saxon Court, to help him with the publication.

In May 1798, Casanova was alone in Dux. He foresaw his death and asked for members of his family currently residing in Dresden to come and support him in his last moments. Carlo Angiolini, the husband of Casanova's niece, traveled without delay from Dresden to Dux. After Casanova's death, he returned to Dresden with the manuscript. Carlo himself died in 1808 and the manuscript passed to his daughter Camilla. Because of the Napoleonic Wars, the climate was not favorable for publishing the memoirs of a character belonging to a past age. After the Battle of Leipzig (1813), Marcolini remembered the manuscript and offered 2500 thalers to Camilla's tutor, who judged the offer too modest and refused.

After some years, the recession compromised the wealth of Camilla's family. She asked her brother Carlo to quickly sell the manuscript. In 1821, it was sold to the publisher Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Brockhaus asked Wilhelm von Schütz to translate the book into German. Some extracts of the translation and the first volume were published as early as 1822. The collaboration between Brockhaus and Schütz stopped in 1824, after the publication of the fifth volume. The other volumes were then translated by another unknown translator.

Due to the success of the German edition, the French editor Victor Tournachon decided to publish the book in France. Tournachon had no access to the original manuscript, and so the French text of his edition was translated from the German translation. The text was heavily censored. In response to the piracy Brockhaus brought out a second edition in French, edited by Jean Laforgue (1782–1852) which was very unreliable as Laforgue altered Casanova's religious and political views as well as censoring sexual references. The French volumes were published from 1826 to 1838. These editions were also successful, and another French pirate edition was prepared with another translation from the German edition. As the German edition was not entirely published at this time, this edition allegedly contains passages invented by the translator.[2]

From 1838 to 1960, all the editions of the memoirs were derived from one of these editions. Arthur Machen used one of these inaccurate versions for his English translation published in 1894 which remained the standard English edition for many years.

The original manuscript was stored in the editor's head office in Leipzig until 1943, when after the closure of the office, Brockhaus himself secured them in a bank, saving them just before the 1943 bombings of Leipzig. In June 1945, it was moved to the new head office in Wiesbaden by the American troops.[4] In 1960, a collaboration between Brockhaus and the French editor Plon led to the first original edition of the manuscript.

In 2010, thanks to the support of an anonymous donor, the manuscript was purchased by the Bibliothèque nationale de France for over $9 million, the institution's most expensive acquisition to date.[4][5][6]

Main editions

Schütz translation (1822–1828)

This first edition is a censored German translation for Brockhaus (the first half was translated by Wilhelm von Schütz, the remaining parts by an unknown translator). Its "original" title is: Aus den Memoiren des Venetianers Jacob Casanova de Seingalt, oder sein Leben, wie er es zu Dux in Böhmen niederschrieb. Nach dem Original-Manuscript bearbeitet von Wilhelm von Schütz.

Tournachon-Molin translation (1825–1829)

The success of the first German edition spawns the pirate Tournachon-Molin edition, without access to the original manuscript. The first French edition is a German to French translation from the French to German Schütz translation, which results in a very approximate and imperfect text.

Laforgue adaptation (1826–1838)

In reaction to the pirate edition, Brockhaus decided to publish its own French edition. This edition was done with the original manuscript, but still heavily censored and "arranged" by Jean Laforgue. Laforgue rewrote parts of the text, and even added some others of his own.[2] Furthermore, four chapters of the manuscript were not returned to the publisher. The edition was prepared from 1825 to 1831, but difficulties with the censors slowed the publishing of the volumes, especially after the book had been put in the list of Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1834.[7]

Several editions are in fact re-editions of this Laforgue edition:

- Garnier edition (1880). This is a popular and cheap edition.

- The La Sirène edition (1924-1935).

- The first Pléiade edition (1958-1960).

Busoni pirate edition (1833–1837)

The Laforgue edition success spawned a new pirate edition in France. This new edition began as a copy of the first eight published volumes of the Laforgue edition, but because the other volumes of the Laforgue edition were slow to appear (because of censorship), the publisher Paulin asked a journalist, Philippe Busoni, to take over the balance of the project. Busoni wrote the two remaining volumes using the Tournachon-Molin translation, adding new episodes he invented.

Several reeditions of the Busoni edition are:

- The Rozez reedition (1860).

- The Flammarion reedition (1871–1872).

The Brockhaus-Plon reference (1960–1962)

The manuscript remained hidden for many years because Brockhaus didn't want it to be pirated further. Then wars and economics crises slowed their edition projects until the end of the 1950s.

The first complete and authentic edition of the text was published between 1960 and 1962 (minus the four lost chapters, replaced by their Laforgue version, with the annotations by Schütz).

The Bouquins reedition (1993) has since become the first French reference edition.[8]

The new Pleiade edition (2013–2015)

Following the acquisition of the manuscript by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, a new Pléiade edition, based on the manuscript, was published from 2013 to 2015.[3][9]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Histoire de ma vie |

Bibliography

- Jacques Casanova de Seingalt Vénitien, Histoire de ma vie, Wiesbaden & Paris: F. A. Brockhaus & Librarie Plon, 12 vol. in 6, 1960 The first edition of the original text (4 lost chapters being replaced with text from the Laforgue edition), with notes coming from the Schütz edition.

- Jacques Casanova de Seingalt, Histoire de ma vie: Texte intégral du manuscrit original, suivi de textes inédits, Édition présentée et établie par Francis Lacassin, Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 3 vol., 1993 Reedition of the Brockhaus-Plon edition. This edition has become the de facto reference edition.[8]

Translations

Casanova's memoirs have been published in more than 20 languages and 400 editions, mostly in French, English, and German. The main translations are now all based on the Brockhaus-Plon reference. The only unabridged English translation so based is that by Willard R. Trask, cited below.[10] For the first part of that work, Trask won the inaugural U.S. National Book Award in category Translation (a split award).[11]

- German

- Aus den Memoiren des Venetianers Jacob Casanova de Seingalt [etc.], Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 12 vol. (6227 pages), 1822–1828. The Wilhelm von Schütz censored translation of the original manuscript. Regularly reedited beginning in 1850.

- Geschichte meines Lebens, Berlin: Propyläen, 12 vol. (4717 pages), 1964–1967. Heinz von Sauter complete translation of the Brockhaus-Plon edition of the original manuscript. Reedited in 1985.

- English

- The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt, [London]: Privately printed [Bartholomew Robson], 12 vol. (approx. 4000 pages), 1894. Arthur Machen complete translation of the censored Laforgue text. Regularly reedited, including the revised Arthur Symons translation, in 1902, then in 1940.

- History of My Life, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 12 vol. in 6 (4,568 pages), 1966–1971. Willard R. Trask complete translation of the Brockhaus-Plon reference.

See also

- Fellini's Casanova, a 1976 feature film by Federico Fellini

References

- The manuscript can be viewed in the site gallica.bnf.fr.

- Symons, Arthur, Casanova at Dux, ebooks.adelaide.edu.au, retrieved 2009-06-27,

This manuscript, in its original state, has never been printed. (...) Herr Brockhaus employed a certain Jean Laforgue, a professor of the French language at Dresden, to revise the original manuscript, correcting Casanova’s vigorous, but at times incorrect, and often somewhat Italian, French according to his own notions of elegant writing, suppressing passages which seemed too free-spoken from the point of view of morals and of politics, and altering the names of some of the persons referred to, or replacing those names by initials. (...) This, however far from representing the real text, is the only authoritative edition, and my references throughout this article will always be to this edition.

- Lire (enfin) Casanova: l'original dans la Pléiade, The Huffington Post, 2013-04-18, retrieved 2017-01-14

- La BNF acquiert de précieux manuscrits de Casanova, france24, archived from the original on 2012-10-23, retrieved 2010-02-22,

Notre maison d'édition à Leipzig a été fermée en 1943 par les Nazis. Mon grand-père a alors pris les manuscrits et les a emportés à vélo pour les déposer dans le coffre de sa banque", a raconté M. Brockhaus. "C'est ainsi qu'ils ont pu être sauvés" du bombardement de la ville. Ils ont été acheminés en 1945 par les Américains à Wiesbaden.

- Racy Memoir for the French National Library, The New York Times, 2010-02-21, retrieved 2013-01-20,

The French National Library has bought itself a belated valentine in the form of manuscript pages by the hand of the world’s most famous lover, Giacomo Casanova, Reuters reported

- "Actualités". BnF - Site institutionnel. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- Modern History Sourcebook: Index librorum prohibitorum, 1557–1966, fordham.edu, retrieved 2009-06-27

- Pons, Alain (1993-12-16), Casanova grandeur nature, L'Express, retrieved 2009-06-29

- Histoire de ma vie, tome I, Casanova en La Pléiade, lacauselitteraire.fr, 2013-10-24, retrieved 2017-01-14

-

Smith, Dinitia (1997-10-01), Learning to Love a Lover; Is Casanova's Reputation as a Reprobate a Bum Rap?, The New York Times, retrieved 2009-06-27,

But for the most part it has been nearly impossible to read Casanova's memoirs in English. They have long been out of print and difficult to obtain. Now, for the first time in over 25 years, they are available once again, in an attractively bound six-volume edition of a 1966 translation by Willard R. Trask

- "Casanova's History of My Life National Book Awards 1967 for Translation". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2019-07-08. There was a "Translation" award from 1967 to 1983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Histoire de ma vie. |

- The original manuscript can be viewed in the site of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

- History of Casanova's Manuscripts

- Gutenberg etexts

- Memoirs

- Memoirs of Jacques Casanova, Arthur Machen 1894 edition

- Memoirs, French Laforgue reprinted 1880 edition

- Interview with historian Larry Wolff on Histoire de ma vie