Hildebrand & Wolfmüller

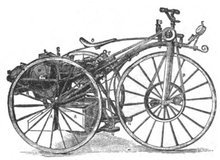

The Hildebrand & Wolfmüller was the world's first production motorcycle.[1][5][6] Heinrich and Wilhelm Hildebrand were steam-engine engineers before they teamed up with Alois Wolfmüller to produce their internal combustion Motorrad in Munich in 1894.[1]

| |

| Manufacturer | Heinrich Hildebrand, Wilhelm Hildebrand & Alois Wolfmüller |

|---|---|

| Production | 1894–1897[1] |

| Engine | 1,489 cc (90.9 cu in) 360° two-cylinder water-cooled four-stroke, with surface carburetor[2][3] |

| Bore / stroke | 90 mm × 117 mm (3.5 in × 4.6 in) |

| Top speed | 28 mph (45 km/h)[1] |

| Power | 2.5 bhp (1.9 kW) @ 240 rpm[1] |

| Ignition type | Hot tube |

| Transmission | Direct drive via connecting rods[2][3] |

| Frame type | Steel tubular duplex,[2] step-through |

| Brakes | spoon brake, friction against front tire |

| Tires | pneumatic, front 26 in (66 cm), rear 22 in (56 cm)[4] |

| Weight | 110 lb (50 kg)[4] (dry) |

Mechanical details

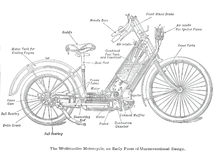

The Hildebrand & Wolfmüller patent of 20 January 1894, No. 78553 describes a 1,489 cc (90.9 cu in) two-cylinder, four-stroke engine, with a bore and stroke of 90 mm × 117 mm (3.5 in × 4.6 in). It produced 1.9 kW (2.5 bhp) @ 240 rpm[1] propelling a weight of 50 kg (110 lb)[4] up to a maximum speed of 45 km/h (28 mph).[1]The fuel-air mixture from the surface carburettor was regulated by a valve operated by controls on the handlebar.[2][5] The engine, which was positioned flat in the frame, used hot tube ignition with the tube heater in front of the cylinder heads. The tube heater was ventilated by the lower downtubes while the upper downtubes held lubricating oil.[3]

Some design details were carried over from a steam-powered prototype made by the Hildebrand brothers in 1889, including the water tank shaped to form the rear mudguard and the connecting rods of the engine driving the rear wheel directly. The water tank was repurposed to supply water to the cooling jackets surrounding the cylinders.[7] The steam-powered prototype had a double-acting cylinder, applying power to the piston in both directions.[8] With no double action available in the petrol engine, and no flywheel effect apart from the movement of the rear wheel, the return impulse for the piston was provided by heavy rubber bands.[3]

The intake valves were operated by the suction caused by the intake stroke, while the exhaust valves were operated by an eccentric brass ring on the rear wheel and a device at the cylinder head that opened each cylinder's valve alternately.[3]

Production run

Approximately two thousand examples of this motorcycle were built,[5] but with a high initial purchase price and fierce competition from improving designs (this model was entirely "run and jump" with neither clutch nor pedals) it is not thought to have been a great commercial success. The Hildebrand & Wolfmüller factory closed in 1919 after the First World War.[1][4] The motorcycle was also built under licence in Paris by Duncan and Superbie.[3]

Survivors

Examples exist today in the Deutsches Zweirad- und NSU-Museum in Neckarsulm, Germany, the Science Museum in London, The Henry Ford in Detroit, Michigan, the Museum Lalu Lintas in Surabaya, Indonesia, National Technical Museum in Prague, and the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum in Birmingham, Alabama, USA.[9] Until 2011, the Wells Auto Museum in Wells, Maine listed an 1894 Wolfmuller in their collection.[10]

Notes

- Walker & 2001 103.

- Partridge 1976, p. 16.

- Wilson 1995, pp. 82-83.

- Pagé 2004, pp. 23–25.

- Wilson 1995, p. 82.

-

- Brown 2004, pp. 14–15

- Brown 2005, pp. 6–7

- de Cet 2001, p. 121

- Partridge 1976, pp. 8, 11, 16.

- Partridge 1976, pp. 8, 11.

- Mijarto 2009.

- Our Collection, Wells Auto Museum, 2010, archived from the original on May 30, 2010

References

- Brown, Roland (2004), History of the Motorcycle: From the first motorized bicycles to the powerful and sophisticated superbikes of today, Bath, England: Parragon, pp. 10–11, 14–15, ISBN 1-4054-3952-1

- Brown, Roland (2005), The Ultimate History of Fast Motorcycles, Bath, England: Parragon, p. 6–7, ISBN 1-4054-5466-0

- de Cet, Mirco (2001), The Complete Encyclopedia of Classic Motorcycles: informative text with over 750 color photographs (3rd ed.), Rebo, p. 121, ISBN 90-366-1497-X

- Mijarto, Pradaningrum (7 August 2009), "Kereta Setan" Bikin Takjub Warga (in Indonesian), retrieved 2011-07-11

- Pagé, Victor Wilfred (2004) [1924], Early Motorcycles: Construction, Operation and Repair, Dover Books on Transportation, Dover Publications, pp. 23–25, ISBN 0-486-43671-3

- Partridge, Michael (1976), Motorcycle Pioneers: The Men, the Machines, the Events 1860-1930, David & Charles (Publishers), pp. 8, 11, 16, ISBN 0 7153 7 209 2

- Walker, Mick; Guggenheim Museum Staff (2001) [1998], Krens, Thomas; Drutt, Matthew (eds.), The Art of the Motorcycle, Harry N. Abrams, p. 103, ISBN 0810969122

- Wilson, Hugo (1995), "The A-Z of Motorcycles", The Encyclopedia of the Motorcycle, London, UK: Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 0 7513 0206 6

See also

External links

![]()

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

Fastest production motorcycle 1894–1901 |

Succeeded by Werner New Werner |