Hersfeld Abbey

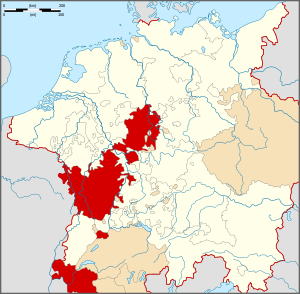

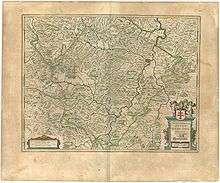

Hersfeld Abbey was an important Benedictine imperial abbey in the town of Bad Hersfeld in Hesse (formerly in Hesse-Nassau), Germany, at the confluence of the rivers Geisa, Haune and Fulda.[1]

Imperial Abbey of Hersfeld Reichsabtei Hersfeld | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 775–1606 (de facto) 775–1648 (de jure) | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

Hersfeld Abbey: church ruins | |||||||||

| Status | Imperial Abbey | ||||||||

| Capital | Hersfeld Abbey | ||||||||

| Government | Theocracy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Founded by Saint Boniface | 736–42 | ||||||||

| 775 | |||||||||

1371 | |||||||||

• Forced union with Fulda | 1513–15 | ||||||||

1525 | |||||||||

• Otto, Prince of Hesse, elected lay administrator | 1606 | ||||||||

| 1648 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

History

Hersfeld was founded by Saint Sturm, a disciple of Saint Boniface, in 736–742. Because its location rendered it vulnerable to attacks from the Saxons, however, he transferred it to Fulda. Some years later, in or about 769 after the defeat of the Saxons by the Franks, Lullus, archbishop of Mainz, re-founded the monastery at Hersfeld.

Charlemagne (who had recently succeeded to the Frankish royal crown) and other benefactors provided endowments,[1] and in 775 gave it the status of a Reichsabtei "imperial abbey" (i.e., territorially independent prince-abbacy within the Empire).[1]

Pope Stephen III granted it exemption from episcopal jurisdiction. It soon possessed 1050 hides of land and a community of 150 monks.[1]

Lullus was buried in the church at his death in 786. The abbey buildings were extended between 831 and 850, and in 852 Lullus' grave was moved to the new basilica. During this ceremony Lullus' canonisation was formally announced by Rabanus Maurus. (The "Lullusfest", or "Feast of Saint Lullus", has been celebrated in Hersfeld since then, on 16 October and is the longest-established local festival in the German-speaking world).

During the abbacy of Abbott Druogo (875–892) the first known Hersfeld Tithe Register was written from 881 onwards. An additional tithe register was prepared before 899 during the abbacy of Abbott Harderat.

The abbey had already become a place of pilgrimage after 780, because of the relics of Saint Wigbert which were brought here at that time, and the miracles that they were said to cause. A valuable library was collected, the annals of the monastery were regularly kept, and it became well known as a seat of piety and learning. Towards the close of the 10th century, Hersfeld suffered from the general decline of the age, and monastic discipline became relaxed. Some years later, however, the observance was reformed by Saint Gotthard (afterwards Bishop of Hildesheim), and members of the community were sent out to other houses of the order to carry out in them the work of religious revival.[1]

During the Investiture Controversy, Hersfeld took the side of the imperial cause against the papacy. Emperor Henry IV himself visited it quite often, sometimes accompanied by his wife; and his son and successor son Conrad of Italy was born and baptized within the precincts of the abbey. In the last decade of the 11th century the abbey seems to have been fully restored to papal favour, and it continued to prosper for a long subsequent period.[1]

The town of Hersfeld, now Bad Hersfeld, grew up outside the abbey, and flourished, to the extent that it found itself strong enough to assert its independence, and in 1371 formally placed itself under the protection of the Landgraves of Hesse.[1]

As time went on the state of the monastery again deteriorated, and in 1513 it had reached such a low point that abbot Volpert Riedesel resigned his office into the hands of Pope Leo X, and the abbot of Fulda was authorized by the Emperor Maximilian to incorporate the house into his own abbey. According to a contemporary account, the library was in a state of ruin and decay, many precious volumes had altogether disappeared, and manuscripts containing the archives and records of the house were used in the kennels as litter for the dogs.[1]

Reformation

This forced union between Hersfeld and Fulda lasted little more than two years, after which a new abbot of Hersfeld was chosen. Abbot Krato, who held office in 1517, was however in sympathy with Lutheranism. (Martin Luther stopped at the abbey on his return from the Diet of Worms in 1521 and gave a sermon). Krato swore allegiance to the Lutheran Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, in 1525. The abbey church was consequently closed to Roman Catholic worship, Mass being said only in a chapel inside the monastery.[1]

Dissolution

For the rest of the century the abbey continued as a Protestant establishment under the close supervision of the rulers of Hesse, and on the death of the last abbot (Joachim Röll) in 1606, Otto, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, was elected lay administrator.[1]

The pope made a vain attempt, after Otto's death, to bring the abbey back under Catholic administration. It continued in the hands of the princely family until after the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648,[1] Hersfeld, as an imperial fief, was united to Hesse as a secularised principality.

Buildings

The abbey church, in the Romanesque style, was built in the early part of the 12th century, but was used as a powder magazine and then destroyed by the French in 1761 during the Seven Years' War.[1] The ruins are now a well-known venue for concerts and public events, and are the site of the annual "Bad Hersfeld Festival".

The Katharinenturm (tower) still stands. Within it is the Lullusglocke, Germany's oldest cast bell dated to 1038.

Burials

- Saint Lullus

- Saint Wigbert

Annals

The annals of the abbey, the "Annales Hersfeldienses", are a significant source of medieval German history.[1]

See also

- List of Carolingian monasteries

- Carolingian architecture

- Carolingian art

- Regional characteristics of Romanesque architecture

References

-