Herodes Atticus

Herodes Atticus (Greek: Ἡρῴδης ὁ Ἀττικός, Hērōidēs ho Attikos; AD 101–177),[1] or Atticus Herodes,[2] son of Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes (suffect consul 133), was a Greco-Roman politician and sophist who served as a Roman senator. Appointed consul at Rome in 143, he was the first Greek to hold the rank of consul ordinarius, as opposed to consul suffectus. In Latin, his full name was given as Lucius Vibullius Hipparchus Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes (Greek: Λεύκιος Βιβούλλιος Ἵππαρχος Τιβέριος Κλαύδιος Ἀττικὸς Ἡρῴδης).[1] According to Philostratus, Herodes Atticus was a notable proponent of the Second Sophistic. M.I. Finley described Herodes Atticus as "patron of the arts and letters (and himself a writer and scholar of importance), public benefactor on an imperial scale, not only in Athens but elsewhere in Greece and Asia Minor, holder of many important posts, friend and kinsman of emperors."[3]

Ancestry and family

Herodes Atticus was a Greek of Athenian descent. His ancestry could be traced to the Athenian noblewoman Elpinice, a half-sister of the statesman Cimon and daughter of Miltiades.[1] He claimed lineage from a series of mythic Greek kings: Theseus, Cecrops, and Aeacus, as well as the god Zeus. He had an ancestor four generations removed from him called Polycharmus, who may have been the Archon of Athens of that name from 9/8 BC–22/23.[4] His family bore the Roman family name Claudius. There is a possibility that a paternal ancestor of his received Roman citizenship from an unknown member of the Claudian gens.

Herodes Atticus was born to a distinguished and very rich family of consular rank.[5] His parents were a Roman Senator of Greek descent, Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes, and the wealthy heiress Vibullia Alcia Agrippina.[1][6][7] He had a brother named Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodianus and a sister named Claudia Tisamenis.[1] His maternal grandparents were Claudia Alcia and Lucius Vibullius Rufus, while his paternal grandfather was Hipparchus.[7]

His parents were related as uncle and niece.[6][7][8] His maternal grandmother and his father were sister and brother.[7][8] His maternal uncle Lucius Vibullius Hipparchus was an Archon of Athens in the years 99–100[7][9] and his maternal cousin, Publius Aelius Vibullius Rufus, was an Archon of Athens between 143–144.[7][9]

Life

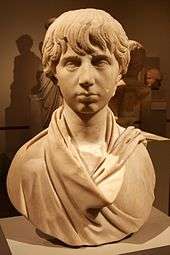

.jpg)

Herodes Atticus was born in Marathon, Greece,[10] and spent his childhood years between Greece and Italy. According to Juvenal[11] he received an education in rhetoric and philosophy from many of the best teachers from both Greek and Roman culture.[12] Throughout his life, however, Herodes Atticus remained entirely Greek in his cultural outlook.[12]

He was a student of Favorinus, and inherited Favorinus' library.[13] Like Favorius, he was a harsh critic of Stoicism.

these disciplines of the cult of the unemotional, who want to be considered calm, brave, and steadfast because they show neither desire nor grief, neither anger nor pleasure, cut out the more active emotions of the spirit and grow old in a torpor, a sluggish, enervated life.[14]

The Emperor Hadrian in 125 appointed him Prefect of the free cities in the Roman province of Asia. He later returned to Athens, where he became famous as a teacher. In the year 140, Herodes Atticus was elected and served as an Archon of Athens. Later in 140, the Emperor Antoninus Pius invited him to Rome from Athens to educate his two adopted sons, the future Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. Sometime after, he was betrothed to Aspasia Annia Regilla, a wealthy aristocrat, who was related to the wife of Antoninus Pius, Faustina the Elder.[15] When Regilla and Herodes Atticus married, she was 14 years old and he was 40. As Herodes Atticus was in favor with the Emperor, as a mark of his friendship Antoninus Pius appointed him Consul in 143.

Herodes Atticus and Regilla controlled a large tract around the Third Mile of the Appian Way outside Rome, which was known as the "Triopio" (from Triopas, King of Thessaly). For his remaining years he travelled between Greece and Italy.

Some time after his consulship, he returned to Greece permanently with his wife and their children.

Herodes Atticus was the teacher of three notable students: Achilles, Memnon and Polydeuces (Polydeukes). "The aged Herodes Atticus in a public paroxysm of despair at the death of his perhaps eromenos Polydeukes, commissioned games, inscriptions and sculptures on a lavish scale and then died, inconsolable, shortly afterwards."[16]

Herodes Atticus had a distinguished reputation for his literary work, most of which is now lost,[12] and was a philanthropist and patron of public works. He funded a number of building projects, including:

- A Stadium – Athens

- Odeon – Athens

- A theater at Corinth

- A stadium at Delphi

- The baths at Thermopylae

- An aqueduct at Canusium in Italy

- An aqueduct at Alexandria Troas

- A nymphaeum (monumental fountain) with his wife at Olympia

- various benefactions to the peoples of Thessaly, Epirus Euboea, Boeotia and Peloponnesus

Throughout his life, Herodes Atticus had a stormy relationship with the citizens of Athens, but before he died he was reconciled with them.[12] When he died, the citizens of Athens gave him an honored burial, his funeral taking place in the Panathinaiko Stadium in Athens, which he had commissioned.[12]

Children

Regilla bore Herodes Atticus six children, of whom three survived to adulthood. Their children were:

- Son, Claudius – born and died in 141[1]

- Daughter, Elpinice – born as Appia Annia Claudia Atilia Regilla Elpinice Agrippina Atria Polla, 142–165[1]

- Daughter, Athenais – born as Marcia Annia Claudia Alcia Athenais Gavidia Latiaria, 143–161[1]

- Son, Atticus Bradua – born in 145 as Tiberius Claudius Marcus Appius Atilius Bradua Regillus Atticus[1]

- Son, Regillus – born as Tiberius Claudius Herodes Lucius Vibullius Regillus, 150–155[1]

- Unnamed child who died with Regilla or died even perhaps three months later in 160[1]

After Regilla died in 160, Herodes Atticus never married again. When he died in 177, his son Atticus Bradua and his grandchildren survived him. Sometime after his wife's death, he adopted his cousin's first grandson Lucius Vibullius Claudius Herodes as his son.[17]

Legacy

Herodes Atticus and Regilla, from the 2nd century until the present, have been considered great benefactors in Greece, in particular in Athens. The couple are commemorated in Herodou Attikou Street and Rigillis Street and Square, in downtown Athens. In Rome, their names are also recorded on modern streets, in the Quarto Miglio suburb close to the area of the Triopio. During his life, he built a theater called the Odeon of Herodes Atticus to honor Regilla after her death in 160 AD.[18]

References

- Pomeroy, The murder of Regilla: a case of domestic violence in antiquity

-

- Finley, The Ancient Economy (Berkeley: University of California, 1973), p. 100

- Day, J., An economic history of Athens under Roman domination p. 238

- Wilson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece p.p. 349-350

- Wilson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece p. 349

- Graindor, P., Un milliardaire antique p. 29

- Day, J., An economic history of Athens under Roman domination p. 243

- Sleepinbuff.com Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Article, Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes, Microsoft Encyclopedia 2002

- Juvenal, Satire III

- Wilson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece p. 350

- Wytse Hette Keulen "Gellius the Satirist: Roman Cultural Authority in Attic Nights" p119

- Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights, 19.12

- Pomeroy, The murder of Regilla: a case of domestic violence in antiquity p. 14

- Lambert, Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous, p. 143.

- Graindor, Un milliardaire antique p. 29

- "Herodes Atticus theatre in Athens - Greeka.com". Greeka. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

Sources

Primary sources

- Philostratus, Lives of the Sophists, 2.1 (paragraphs 545–566)

- Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights

- Philostratus, Leben der Sophisten. Greek and German by Kai Brodersen. Wiesbaden: Marix 2014, ISBN 978-3-86539-368-5

Secondary material

- Gibbon, E., The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

- Day, J., An economic history of Athens under Roman domination, Ayers Company Publishers, 1973

- Graindor, P., Un milliardaire antique, Ayers Company Publishers, 1979

- Kennell, Nigel M. "Herodes and the Rhetoric of Tyranny", Classical Philology, 4 (1997), pp. 316–362.

- Lambert, R., Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous, Viking, 1984.

- Papalas, A. J, "Herodes Atticus: An essay on education in the Antonine age", History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Summer, 1981), pp. 171–188.

- Tobin, Jennifer, Herodes Attikos and the City of Athens: Patronage and Conflict Under the Antonines, J. C. Gieben, 1997.

- Potter, David Stone, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 18–395, Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-10058-8

- Wilson, N. G., Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, Routledge 2006

- Pomeroy, S. B., The murder of Regilla: a case of domestic violence in antiquity, Harvard University Press, 2007

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Herodes Atticus. |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by (Sulpicius?) Julianus, and Titus Julius Castus as suffect consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 143 with Gaius Bellicius Flaccus Torquatus |

Succeeded by Quintus Junius Calamus, and Marcus Valerius Junianus as suffect consuls |