Herjolfsnes

Herjolfsnes was a Norse settlement in Greenland, 50 km northwest of Cape Farewell. It was established by Herjolf Bardsson in the late 10th century and is believed to have lasted some 500 years. The fate of its inhabitants, along with all the other Norse Greenlanders, is unknown. The site is known today for having yielded remarkably well-preserved medieval garments, excavated by Danish archaeologist Paul Norland in 1921. Its name roughly translates as Herjolf's Point or Cape.

Establishment

As noted in the Landnámabók (Icelandic Book of Settlements), Herjolf Bardsson was one of the founding chieftains of the Norse colony in Greenland, and was said to be "a man of considerable stature."[1] He was part of an exodus from Iceland accompanying Erik the Red, who led an expedition of colonists in 25 ships in AD 985. Landing on Greenland's southwest coast, Erik and his other kinsmen almost invariably chose to settle further inland away from the open Labrador Sea, at the heads of the fjords where the land was better suited to farming. By contrast, Herjolf's decision to establish himself at the end of a fjord directly facing the open ocean near Greenland's southernmost tip suggests that his primary intention was not farming, but rather the establishment of the new colony's major port of call for incoming ships from Iceland and Europe.[2]

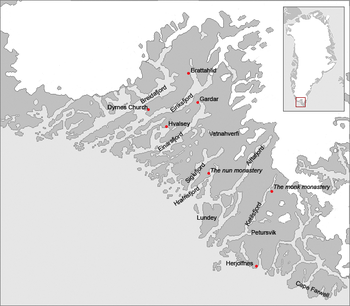

Herjolf's homestead was situated on the west shore of a fjord that came to bear his name, Herjolfsfjord, and was the southern- and easternmost major homestead of the colony's Eastern Settlement.

According to The Greenlanders Saga, Herjolfsnes played a significant role in the Norse discovery of North America. Herjolf's son Bjarni had been conducting business in Norway and returned to Iceland to spend Yule at the family's homestead, only to learn Herjolf had joined the exodus to the new Greenland colony. Bjarni set out to follow Herjolf, but was blown off course to the southwest, becoming the first known European to skirt, if not land on, the North American coast. Realizing he had overshot Greenland, Bjarni reversed course to the northeast and came to a land that matched the description he had been given. The saga states, "...they landed in the evening under a ness; and there was a boat by the ness, and just here lived Bjarni's father, and from him has the ness taken its name, and is since called Herjolfsness."[3] The saga then relates how Bjarni travelled to Norway and made his discovery known to the court of Erik Jarl. Erik is said to have treated him well, but others in the court criticized Bjarni's lack of initiative for failing to explore the new lands he had seen. Upon Bjarni's return to Herjolfsnes, he is said to have given up seafaring and lived there with his father, and upon Herjolf's death "afterwards dwelt there" presumably as the chieftain of the homestead and the immediate district.

In Erik The Red's Saga (which covers essentially the same events as the Greenlanders Saga), the famous Icelander Gudrid Thorbjornsdottir is said to have landed at Herjolfsnes after a difficult journey, and lived there for a while. Curiously, this saga describes the homestead as being owned by a man named Thorkell, and makes no mention of Herjolf or Bjarni. Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad believed that the saga's author may have written the two men out of the story in order to elevate the exploits of Leif Eriksson, the first known European to land in North America.[4] By contrast, in The Greenlanders Saga, Leif is said to have prepared for his voyage to Vinland by purchasing Bjarni's ship, during which he presumably received counsel and directions from Bjarni.

After the colony's conversion to Christianity in AD 1000, Herjolfsnes was one of 16 known sites in the Eastern Settlement on which a church was raised. The ruins that are visible today are those of a church built in the 13th century, which was likely raised on the site of an older, conversion-era church. It had a rectangular foundation similar to that of the churches at Hvalsey and Brattahlid further north in a style that was common in medieval northern Europe. The Herjolfsnes church was the 3rd largest in the Norse Greenland colony, behind Gardar and Brattahlid.[5] Gardar was the seat of Norse Greenland's bishopric and also the seat of its Althing parliament, while Brattahlid was the most prominent single homestead due to its association with Erik The Red and his descendants, so Herjolfsnes' comparably sized church is an indication of the homestead's relative importance and stature among the Norse Greenland settlements.

The church's graveyard contained the remains of local inhabitants and also of those who had died during ocean voyages to the colony. One account tells of 12th century Icelanders who were shipwrecked on the east coast and perished while trying to cross the inland glaciers in an attempt to reach Herjolfsnes, only to be buried there instead. For bodies lost or buried at sea, it appears to have been the custom to carve commemorative runes onto a stick which was then placed in the Herjolfsnes graveyard when the ship made landfall there. One such runestick found at Herjolfsnes reads, "This woman, whose name was Gudveg, was laid overboard in the Greenland Sea."[6]

%2C_fr%C3%A5n_Danmark_-_KMB_-_16000300015527.jpg)

Some of the deceased at Herjolfsnes had been laid to rest in wooden coffins. However, perhaps owing to the scarcity of wood, it increasingly became the practice to wrap the deceased in layers of wool clothing.[7] This practice inadvertently created a treasure trove of medieval textile and fashion artifacts when the graves and well-preserved clothes were excavated in the early 20th century.

Later history

Ivar Bardarson, a Norwegian priest who lived in the colony for nearly 20 years in the mid 14th century as a representative of the Norwegian Crown and the Catholic church, wrote that Herjolfsnes served as the major harbour for Greenland's inbound and outbound traffic and was well known to North Atlantic sailors, who referred to it as "Sand".[8] It is not clear if the harbour was in the immediate area of the church and homestead. The nearby Makkarneq Bay, which offers much better shelter than Herjolfsnes proper, features several Norse ruins that appear to include the foundations of stone warehouses, and is thus a possible site of the Sand harbour that Bardarson described.[9]

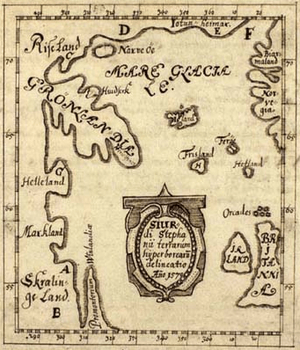

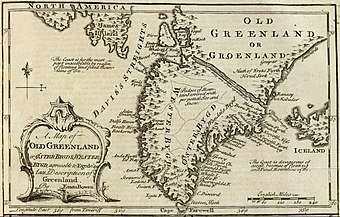

Herjolfsnes is the only Greenland settlement shown on the Skálholt Map from the late Middle Ages, which shows the North Atlantic's European and North American coastlines as perceived by Norse explorers.

Contact with other peoples

Prior to the arrival of the Norse, successive waves of Paleo-Eskimo cultures had inhabited Greenland, perhaps as far back as 2500 BC. However, the island is believed to have been uninhabited by the time of the Norse arrival, except perhaps for the extreme northwest region, by the Dorset culture. The Little Climatic Optimum then under way would have made the southwest coast especially unsuited to the Dorset's arctic hunter-gatherer way of life; they are believed to have had great difficulty adapting to this warm period, and retreated progressively farther north. As a result, it is believed that the first North American aboriginals that Norse Greenlanders encountered were actually the Beothuk in Newfoundland. It was only later that the Norse came into direct contact with related peoples in Greenland itself, the Thule culture, who supplanted the Dorset throughout the North American Arctic starting circa AD 1000. These contacts likely started when the Norse began to make regular hunting trips far north of their settlements - or to the island's east coast - to obtain walrus and narwhal ivory.

With the advent of the Little Ice Age, Greenland's cooling climate prompted the Thule to increase their southern range, and brought them into greater contact with the Norse than had been the case with the Dorset.

Modern Inuit Greenlanders have oral histories about their ancestors' contact with the Norse, which recount instances of both friendship and hostilities. One legend tells of a Norse chieftain named Ungortoq and his enemy, an Inuit leader named K'aissape who was said to have burned the Hvalsey settlement and pursued Ungortoq from Hvalseyfjord all the way down past Herjolfsnes to Cape Farewell.

Recent archaeological soil testing of Norse and Thule building ruins in Makkarneq Bay a few kilometres west of Herjolfsnes suggests that both peoples occupied the area at the same time.[10] This may be evidence that the Thule were active participants in the Herjolfsnes ivory trade during the Norse period.

Disappearance

Having endured for nearly a half-millennium, the exact fate of the Norse settlers in Herjolfsnes and the entirety of Greenland remains unknown, although several factors were likely involved. The Greenlanders' pastoral way of life would have been severely challenged by the onset of the Little Ice Age, much more so than their counterparts in Europe. DNA analysis of human remains from Herjolfsnes and other settlements shows that marine-based protein (especially from seals) became an increasingly large part of their diet, compared to the pastoral diet of Erik the Red's time. Other theories include the possibility of conflict with Thule Inuit and predation by European pirates. There is no indication from archaeology or human remains that the Norse intermarried with the Thule or adopted their way of life, nor any record from Iceland or Norway that hints of an exodus out of Greenland.

Historical records do suggest that ships from Europe arrived less frequently owing to the worsening sea conditions. The traditional Norse route to reach Greenland was to sail due west from Iceland’s Snæfellsnes peninsula until reaching eastern Greenland’s Ammassalik district, then sailing south along the coast to reach the settlements on the other side of Cape Farewell. However, by the mid-1300’s, Ivar Bardarson noted that the quantity of ice from the northeast was such that "no one sails this old route without putting their life in danger."[11] The Norwegian Crown in Oslo and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nidaros eventually abandoned the colony to its own devices, although some Popes were aware of the situation. By 1448, Pope Nicholas V lamented reports that Greenland ("a region situated at the uttermost end of the earth") had been without a resident Bishop for 30 years (although the last known one, Bishop Alf, actually died earlier, in 1378). These concerns were echoed in a letter dated circa 1500 by Pope Alexander VI, who believed that no communion had been performed in Greenland for a century, and that no ship had visited there in the past 80 years. However, even after the colony was forsaken by the Church and well into the 16th century, the empty title "Bishop of Gardar" continued to be held by a succession of at least 18 individuals, none of whom visited their nominal diocese and only one of whom (Bishop Mattias Knutsson) reportedly expressed any desire to do so.[12]

Although there is no first-hand account of Norse Greenlanders living after 1410, analysis of the clothing buried at Herjolfsnes suggests that there was a remnant population who continued to have some sort of contact with the outside world for at least a few more decades. One pathos-laden account comes from a sailor dubbed Jon The Greenlander, not from origin of birth, but because "...he had drifted to Greenland no fewer than three times...Once when he was sailing with some German merchants from Hamburg, they entered a deep still Greenland fjord...upon going ashore they saw boat-houses, fish-sheds and stone houses for the drying of fish such as are in Iceland...There they found a dead man lying face downwards. On his head was a well-sewn cap. The rest of his garments were partly of wadmal, partly of sealskin. Beside him lay a sheath-knife, much worn from frequent whetting..."[13] Since Herjolfsnes was the only major sea-facing homestead in Norse Greenland, and thus most visible and accessible to visiting ships, many have speculated that Jon The Greenlander's landfall was at or near Herjolfsnes, and the corpse he discovered perhaps being that of the last Norse Greenlander, who perished alone with none to bury him. This account comes from the early 16th century, but it is not clear when the incident actually happened.

Early examination of human remains from the Herjolfsnes churchyard gave rise to a belief that its inhabitants had died out from inbreeding and overall degeneration from extreme cultural and geographic isolation. However, Helge Ingstad disputed this as a faulty assumption that was made after only a cursory analysis of a particularly bad sample of remains. Ingstad asserted that on balance, the Herjolfsnes graveyard shows the picture of a relatively healthy and prosperous people who generally reflected the social and religious mores of Northern European Christendom.[14]

A growing volume of explorers and whalers were once again beginning to land in Greenland by the 16th century, but it was not until the early 18th century that a comprehensive official effort was made by the then-unified Danish-Norwegian crown to re-connect with the lost colony,[15] a job given to Apostle Hans Egede. From reading Icelandic sagas, Egede knew the names of the old Norse homesteads and their associated fjords, but not their locations. A major source of confusion was that the Norse Greenlanders' Eastern, Middle and Western settlements, despite their names, were all located on Greenland's west coast, running south to north respectively. Egede held the then-common mistaken belief that major Eastern Settlement homesteads such as Herjolfsnes were to be found on Greenland's forbidding east coast.[16] Throughout the remainder of his life, Egede was said to have fervently believed in the existence of a remnant population of Norse Greenlanders living in a yet-to-be-found Eastern Settlement, when in fact he had already thoroughly explored its ruins. As a result, maps of Greenland from this period often perpetuated the misunderstanding by showing Herjolfsnes at various locations on the east coast, in contrast to the accurate placement shown on the Skálholt Map nearly two hundred years earlier.

Excavation and discovery of Norse garments

By the early 19th century, visitors and local Inuit had begun finding artifacts and bits of clothing embedded in the western shoreline nearest the Herjolfsnes church ruins: the sea level had risen considerably since the Norse period and was eroding the grounds around the old church. The formal re-discovery of the graveyard (by Europeans) was in the early 19th century when a missionary observed that a nearby Inuit house had a load-bearing doorway that was fashioned from an old tombstone bearing the name Hroar Kolgrimsson. A trading clerk was also said to have found a Norse wool "sailor's jacket" near the church ruins. This prompted a formal excavation attempt in 1839 and the discovery of fair-haired human remains confirmed the site was a Norse cemetery.[17] Subsequent digging in the following decades revealed more artifacts, human remains and garments.

The diggings also revealed other buildings besides the church, including the main house and adjoining banquet hall, a byre and some outbuildings. In the ruins of the church, archaeologists found a significant quantity of charcoal, suggesting a conflagration at some point. The local Inuit's name for the site, Ikigait ("the place destroyed by fire") is further evidence of this.[18] It is possible that other buildings at the site were even closer to the shoreline than the church, and were claimed by the rising sea level some time after the disappearance of the Norse. More recent soil-testing indicates a landslide occurred at some point in the 18th century, and may have eradicated the remains of other Norse buildings at the site.[19]

The increasing number of wadmal fragments and garments being pulled from the ruins - and concern that the rising water line would soon submerge the site - prompted the Danish National Museum to launch an urgent formal excavation in 1921 led by Paul Norland. He estimated that the shoreline had retreated another 12 metres into the cemetery since its rediscovery less than a century before, and was by then nearly touching the remains of the church's southern wall. Comparing Norland's 1921 site plan drawing against modern photographs, the high water line does not appear to have risen significantly since then.

Norland stated in his book, Buried Norsemen at Herjolfsnes, that he'd never worked on a project that attracted such keen interest from the local inhabitants. One woman informed him that she had become so accustomed to finding pieces of preserved Norse wool that she had fashioned children's garments from the centuries-old fabric, but the wool unsurprisingly was not strong enough to make the clothing practical. Working under difficult conditions during the short digging season, Norland and his crew were eventually successful in recovering full and partial costumes, hats, hoods and stockings. The recovery of these clothes is considered one of the most significant European archaeological finds of the 20th century. Prior to the Herjolfsnes diggings, these types of garments had essentially only been seen in medieval paintings. Careful analysis and reconstruction of the garments revealed the skill of the Herjolfsnes inhabitants at spinning and weaving, as well as their desire to follow European fashions such as the cotehardie, the liripipe hood and hats in the Burgunderhuen and Pillbox styles. Later analysis using carbon dating suggests that garments were being manufactured at Herjolfsnes as late as the 1430s.[20]

The garments had been stained a dark brown from being buried, but testing revealed the presence of iron on some of them that appeared to have been deliberately and selectively introduced during manufacture rather than through ground contamination. This suggests that the Herjolfsnes weavers created a non-vegetation-based red dye from a local source of mineral ferric oxide. Although iron was historically used as a mordant for dyes, the Herjolfsnes samples are believed to be the only known instance of medieval Europeans using the mineral to create the red dye itself, presumably in the absence of the madder plant that was commonly used to make red dye back in Europe.[21]

In one sense, the quality, innovation and fashion awareness shown in the Herjolfsnes garments throw even more mystery on the disappearance of the settlement and the Norse colony. As Helge Ingstad observed, "Many of these garments were not worn by common people of Europe, but only by the well-to-do middle class. Altogether the finds testify to a cultivated and fairly prosperous community; certainly not to a people on the brink of extinction."[22]

In addition to the work of Norland himself, the Herjolfsnes clothing has been exhaustively studied by Else Østergård in her books, Woven into the Earth and Medieval Garments Reconstructed.

Later settlement

By the time of the Danish-Norwegian re-colonization of Greenland starting in the 18th century, the former site of Herjolfsnes was known as Ikigait by local Inuit Greenlanders. The community was abandoned at some point in the early 20th century, with the inhabitants perhaps having moved to nearby Narsarmijit on the other side of the fjord. A few concrete and wooden foundations from the time can be seen in current photographs of the site. Herjolfsnes / Ikigait is now uninhabited.

Fictional depiction

In The Greenlanders, a 1988 historical fiction novel by Jane Smiley, Herjolfsnes is depicted as being set apart from the other districts in the Eastern Settlement owing to its location and its wealthy inhabitants, who wore distinct clothing and took pride in their greater knowledge of the outside world.

References

- The Greenlanders Saga

- Farley Mowat, Westviking (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1965), pg. 84-5

- The Greenlanders Saga

- Helge & Anne Stine Ingstad, The Viking Discovery of America (St. John's: Breakwater, 2000) pg. 71

- Helge Ingstad, Land Under the Pole Star (New York: St. Martin's, 1966), pg. 254

- Niels Lynnerup, "The Greenland Norse," Monographs on Greenland no. 24 (1998): pg. 54

- Else Østergård, Woven Into The Earth (Aarhus: Aarhus U Press, 2004) pg. 22

- Land Under the Pole Star, pg. 254

- Jette Arneborg, Saga Trails - Four chieftain’s farmsteads in the Norse settlement of Greenland (The National Museum of Denmark) pg. 75

- Kirsty A. Golding A & Ian A. Simpson, The historical legacy of Anthrosols at Sandhavn (Stirling: University of Stirling, 2010) pg. 22

- Elaine Barrow & Mike Hulme, Climates of the British Isles: Present, Past and Future (London: Routledge, 1997) pg. 129

- Laurence Larson, "The Church In North America" Catholic Historical Review Vol. 5, No. 2/3, (1919) pg. 193.

- Land Under the Pole Star, pg. 294

- Land Under the Pole Star, pg. 256 & 308

- Finn Gad, The History of Greenland: 1700-1782, Volume 2 (London: C. Hurst, 1973) pg. 15

- The History of Greenland, pg. 227

- Woven Into The Earth pg. 17

- Land Under the Pole Star, pg. 254

- Saga Trails, pg. 78

- Woven into the Earth, pg. 144

- Woven into the Earth, pg. 27, 90-91

- Land Under the Pole Star pg. 256

External links

- Satellite view of the Herjolfsnes peninsula.

- A kayker's photograph of the approach to Herjolfsnes, looking northeast. The church ruins are on the middle left immediately above the grey coloured strand.

- A kayaker's photograph of the Herjolfsnes church ruins, looking southeast. The garments discovered by Paul Norland were buried in this immediate area.

- A kayaker's photograph showing birds' eye view of the Herjolfsnes peninsula. The rectangular church foundation can be seen on the middle right.

- A kayaker's photograph showing the view from the top of the headland immediately behind Herjolfsnes, looking southeast toward Cape Farewell.

- A tourist's photograph of the Herjolfsnes church ruins, looking west.

- Images of Herjolfsnes from the Dartmouth College Library's Vilhjalmur Stefansson Collection.

- "The Greenlanders Saga" (English)

- "Erik the Red's Saga" (English)

- "The Book of Settlement" (English)