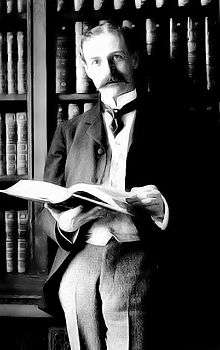

Herbert Putnam

George Herbert Putnam (September 20, 1861 – August 14, 1955)[1] was an American librarian. He was the eighth (and also the longest-serving) Librarian of Congress from 1899 to 1939.[2] He implemented his vision of a universal collection with strengths in many languages, especially from Europe and Latin America.[3]

Herbert Putnam | |

|---|---|

Herbert Putnam | |

| Librarian Emeritus of Congress | |

| In office 1939–1954 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| President of the American Library Association | |

| In office 1903–1904 | |

| Preceded by | James Kendall Hosmer |

| Succeeded by | Ernest Cushing Richardson |

| In office January 1898 – August 1898 | |

| Preceded by | Rutherford P. Hayes |

| Succeeded by | William Coolidge Lane |

| 8th Librarian of Congress | |

| In office 1899–1939 | |

| Appointed by | President William McKinley |

| Preceded by | John Young |

| Succeeded by | Archibald MacLeish |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Herbert Putnam September 20, 1861 New York City, US |

| Died | August 14, 1955 (aged 93) Woods Hole, Massachusetts, US |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte Elizabeth Munroe ( m. 1886) |

| Children | 2, including Brenda |

| Father | George Palmer Putnam |

| Alma mater | |

| Awards |

|

Biography

George Herbert Putnam was born in New York City at 107 East Seventeenth Street,[4] the sixth son and tenth child of Victorine and George Palmer Putnam. The father, one-time collector of internal revenue in New York by appointment of Abraham Lincoln, was the founder of a well-known publishing house,[5] known previously as the Putnam Publishing house, but now known as G. P. Putnam's Sons.[6]

In 1886, Herbert Putnam married Charlotte Elizabeth Munroe of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and together they had two daughters, Shirley and Brenda Putnam.[7] Brenda Putnam grew up to become a celebrated sculptor in the early 20th century, highly known for her "children, cherubs, and garden ornaments."[8] Throughout Herbert Putnam's career, he was described by his colleagues as maintaining "an impenetrable dignity…formal manner, invariable gracious and cordial, covered shyness and a deep reserve. He had few intimates, even among his closest colleagues, but he was fond of good company and good conversation"[9] as well being "painfully modest, a family man who had an unreciprocated view of his staff as family."[10]

He died at his home in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, on August 14, 1955.[7][11]

Early career

After graduating magna cum laude from Harvard University in 1883, Putnam spent the following year at Columbia University Law School.[6] Eventually, however, his interest in administrative work led him to the Minneapolis Athenaeum where he served as librarian in 1887, until it merged into the Minneapolis Public Library in 1888.[6] Putnam was elected city librarian of the Minneapolis Public Library at that time and served while simultaneously being admitted to the Minnesota bar of Law.[6] According to the Honorable Lawrence Lewis of Colorado at a Tribute for Putnam in 1939, Putnam at this time "modernized antiquated methods, revised the charging records of books on loan, inaugurated a new system of cataloging and classification, opened the alcoves to readers, [and] insisted that 'there are two great problems of library management – one to get the books for the readers, the other to get the readers to the books.'"[5] During this time he developed the Putnam Classification System (based in part on work by John Edmands), which would influence his later design of the Library of Congress Classification system.[12]

In 1891, Putnam resigned his Minneapolis post due to his mother-in-law's ill health and promptly returned to Boston to be near her. Putnam "was admitted to the Suffolk bar, and practiced law in Boston until the 18th of February 1895"[13] when he was appointed Librarian of the Boston Public Library. During his tenure at the Boston Public Library "there were 9 branches and 12 delivery stations. At the end of his four years, there were 10 branches, 5 minor branches, called 'reading rooms,' and 56 deposit stations…the library grew from a total of 610,375 volumes at the close of 1894 to 716,050 at the close of 1898."[13] Another contribution made by Putnam towards the Boston Public Library was the addition of a room devoted to juveniles, "believed to have been the first room wholly devoted to the service of children in any of the larger libraries of the country."[13]

Library of Congress

Induction

Putnam's activities with the American Library Association led him to join with Justin Winsor and Melvil Dewey as official delegates to the International Conference of Librarians in London in 1897.[6] When Winsor died shortly thereafter, Putnam served the remainder of his term as President of the ALA.[6] When John Russell Young died in January 1899, President William McKinley requested Congress to appoint Putnam. He was officially confirmed December 12, 1899.[7]

Systemization of a public institution

Upon the confirmation of Putnam to his appointed duty of Librarian of Congress, one daunting task Putnam faced from the onset was the sheer volume of materials that had to be reorganized for the newly opened Thomas Jefferson Building – the newly appointed library for the Library of Congress. However, Putnam was well aware of what needed to be done. "In October 1899 Putnam requested a $190,000 increase in the budget for fiscal 1901. If Congress consented, the 1899 LC budget would nearly double and that for 1900 would be increased by 60 percent. Declaring that the collections were deficient in many respects, [Putnam] asked for $50,000 to purchase new material, more than twice the 1899 appropriation.[14] In summation, the first task of Putnam's administration was to organize all materials of the Library of Congress so they may be used efficiently by the public."

Putnam's request was granted by the United States Congress, and thus an appropriation bill was passed on April 17th, 1900.[15] Although Putnam's administration would need time in order to collect, organize, and disseminate all of the material within the Library of Congress' collection, the task was completed with enormous success. "By 1924 the first objective had been won with – 1) All spaces in the building duly differentiated and equipped for specialized, as well as general, uses. 2) The specialized material installed in appropriate cases. 3) A scheme of classification, systematic and elastic, with an appropriate nomenclature. 4) Adoption of processes of cataloging, including forms of entry, now standardized for American libraries. 5) Actual application of the classification and cataloging to a large portion of the collection of printed books."[16]

Putnam during this time also introduced a new system of classifying books that continues to this day, known as the Library of Congress Classification. He also established an interlibrary loan system, and expanded the Library of Congress's role and relationships with other libraries, through the provision of centralized services. He was elected an Associate Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1902,[17] and elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1907.[18]

War-time service

In July 1916, "former LC staff member Elizabeth West, director of the Carnegie Library of San Antonio, Texas, suggested to Putnam that the Library of Congress cooperate with other libraries to send books to American soldiers."[19]

Initially, Putnam was not interested in the wholesale distribution of books to American troops simply due to the lack of interest. However, when attention arose that the British War Library Service in London were performing similar duties to their troops, measures were quickly devised by Putnam, the ALA, and Congress to enact such a program to the American military branches.[20] "Aided by a grant of $320,000 from the Carnegie Corporation, the War Service built thirty-six libraries, completing the majority by February 1918. But with so much invested in buildings, little money remained for books or administration…Putnam took the matter up directly with the War Department and obtained assurances that the government would provide utilities. He appealed to ALA members to donate books and volunteer for service, and by June 1918 the association had purchased 300,000 books, sent 1,349,000 gift books to camps, and distributed 500,000 magazines."[21] In the time after World War I, the services of the Library of Congress towards the war effort provided a new outlook for the American public on the possibilities of what a successful library could accomplish. In other words, the contributions made by the Library of Congress in that time gave "librarians 'a new conception of what a truly national library could be' and added one more item 'to the long list of benefits for which American libraries have to thank the Library and the Librarian, of Congress."[22]

Retirement

Herbert Putnam's administration as Librarian of Congress lasted for forty years, from 1899 until 1939. It was clear Putnam was not willing to withdraw completely from the world of librarianship, stating: "I would willingly surrender the administration, if that course would serve the interest of the library and I could feel assured as to my successor."[23] Putnam provided the suggestion of "Librarian Emeritus" be developed as his new official title, with an honorarium of one-half of his original salary.[23] On October 1, 1939, Putnam retired as the 8th Librarian of Congress with that title, and he "continued to contribute to the Library, keeping regular office hours for the next 15 years."[7] He was awarded Honorary Membership in the American Library Association in 1940.[24]

Herbert Putnam was succeeded in 1939 by Archibald MacLeish, who served from 1939 until 1944.[25]

Notes

- "(George) Herbert Putnam." Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1977. Biography In Context. Web. 7 Oct. 2013.

- Jane Rosenberg, The Nation's Great Library: Herbert Putnam and the Library of Congress, 1899–1939 (1993)

- John Young Cole, "The library of congress becomes a world library, 1815–2005." Libraries & culture (2005) 40#3: 385–398. in Project MUSE

- Lewis, 1939, p. 3

- Lewis, 1939, p. 4

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 25

- Previous Librarians of Congress, 2008

- Bronze Gallery, 1998–2010

- Rosenberg, 1993, pp. 25, 26

- Knowlton, 2005, p. xx

- "Herbert Putnam". Library of Congress.

- Andy Sturdevant. "Cracking the spine on Hennepin County Library's many hidden charms". MinnPost, 02/05/14.

- Lewis, 1939, p. 5

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 28

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 29

- Lewis, 1939, pp. 7,8

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter P" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 85

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 86

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 87

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 90

- Rosenberg, 1993, p. 153

- American Library Association, Honorary Membership. http://www.ala.org/awardsgrants/awards/176/all_years

- "1939 - Freedom's Fortress: The Library of Congress, 1939-1953". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

References

- Bronze Gallery. (1998–2010, January 1). Brenda Putnam. Retrieved February 1, 2011, from Bronze Gallery: 19th and 20th Century Bronze: http://www.bronze-gallery.com/sculptors/artist.cfm?sculptorID=100

- Knowlton, J. D. (Ed.). (2005). Herbert Putnam: A 1903 Trip to Europe. Lanham, Maryland, USA: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

- Lewis, H. L. (1939). A Tribute to Dr. Herbert Putnam. Washington: United States Government.

- Rosenberg, Jane Aiken. (1993) The Nation's Great Library: Herbert Putnam and the Library of Congress, 1899–1939 (University of Illinois Press, 1993), the major scholarly biography

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Herbert Putnam |

- Works by or about Herbert Putnam at Internet Archive

| Cultural offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Young |

Librarian of Congress 1899–1939 |

Succeeded by Archibald MacLeish |

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

| Preceded by James Kendall Hosmer |

President of the American Library Association 1903–1904 |

Succeeded by Ernest Cushing Richardson |

| Preceded by Rutherford P. Hayes |

President of the American Library Association 1898 |

Succeeded by William Coolidge Lane |