Henry Buehman

Henry Buehman (May 14, 1851 – December 19, 1912) was a German-born American photographer and politician. After completing his apprenticeship, Buehman traveled to the American West, where he worked and traveled before settling in Tucson, Arizona Territory. There he purchased a portrait studio and operated a financially successful photography business. Periodic trips through the surrounding areas allowed Buehman to compile a large portfolio of scenic and Native American images in addition to his portrait work. His accomplishments as a photographer led to opportunities in other fields and Buehman eventually became the mayor of Tucson from 1895 till 1899.

Henry Buehman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Tucson, Arizona | |

| In office January 1895 – January 1899 | |

| Preceded by | William J. Perry |

| Succeeded by | Gustav A. Hoff |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 14, 1851 Bremen, Germany |

| Died | December 19, 1912 (aged 61) Tucson, Arizona |

| Political party | Republican |

Biography

Buehman was born on May 14, 1851 to Ludwig and Annie Buehman in Bremen, Germany.[1] One of eleven children, eight of whom survived to adulthood, young Buehman was educated in the city's public schools before being apprenticed to a photographer at age fourteen.[2][1] Completing his apprenticeship in June 1868, Buehman took a steamship to New York City.[3] He stayed there for two weeks before continuing on to San Francisco, California via Panama.[4]

After reaching San Francisco, Buehman worked for the firm of Bradley & Rulofson.[2][upper-alpha 1] After leaving this position, he owned a photography studio in Visalia for two years before selling it.[4][5] He traveled through California, Nevada, and Utah before reaching Prescott, Arizona Territory.[3] During his time in the Nevada gold fields, Buehman acquired United States citizenship.[4] In Prescott he equipped himself with a wagon and supplies with the intention of traveling into Mexico.[1] Buehman arrived in Tucson on June 4, 1874.[6] There his plans changed and he took a position with a Mexican photographer.[1][upper-alpha 2] A month later, Buehman was advertising his services as a photographer/dentist.[7][upper-alpha 3] He quickly gained a reputation for the quality of his work and purchased his former employer's studio on February 20, 1875, renaming it the Buehman Studio.[8]

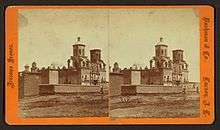

Portrait photography was Buehman's primary source of income. Cartes de visite were popular and his clientele would return to his studio for updated portraits as styles changed to prefer things such as full length or three-quarters poses or cabinet cards instead of smaller hand-held images.[9] When stereographic cards became popular in the American West, Buehman was among the first photographers to produce them.[10] Buehman was rarely a leader of new fashions, but his technical mastery made him the preferred photographer in southern Arizona.[9] His diversified offerings, willingness to adapt to changing tastes, and ability to effectively pose his subjects gained Buehman a loyal base of clients.[11] This gave him opportunities to photograph a variety of prominent territorial residents including Governor John C Fremont, Indian Agent John Clum, General Nelson A. Miles, and rancher Henry Hooker.[12][13][14] His subjects were not limited to the living, with Tucson area residents claiming "even the dead sit for Buehman".[9][15] Sometimes the subjects of Buehman's post-mortem photography were well-known outlaws, but more often a grieving family would hire him to make a lasting keepsake to remind them of a lost child.[16][15]

The Buehman Studio appears to have been financially successful from the beginning.[17] To meet the growing demands of his business, he built a two-story building on the eastern outskirts of town in 1881.[1] The $10,000 building had space for several shops on the ground floor with a photo studio located on the upper story. Large windows and a skylight provided the studio with ample lighting.[18] Locals questioned the wisdom of building "so far out in the wilderness" due to the danger of Apache attacks.[3] The location however proved to be more felicitous then many predicted, with the Bank of Tucson, Western Union, and Wells Fargo and Company renting the ground-floor storefronts.[19] The Tucson Citizen located in an adjacent building, allowed frequent interaction between the studio and the newspaper.[17] After construction of the building was completed, Buehman sold it to Lionel M. Jacobs and leased back the studio.[18] Proceeds of the sale were used to purchase a ranch located on the eastern edge of the Santa Catalina Mountains.[12] Buehman lost the ranch as a result of drought in 1895 and 1896 combined with low beef prices.[20] [21]

Beyond his work in the studio, Buehman took periodic trips through Arizona Territory. In the summer of 1875, he collected flowers, plants, birds nests, eggs and birds with his friend John Spring. The collection was donated to the Smithsonian Institution.[1] A six-week trip to Fort Apache, Fort Bowie, Camp Grant and San Carlos Reservation beginning in December 1875 produced stereoscopic pictures of various Native Americans at the various posts, including Pinal Apache chief Eskiminzin.[22] Later trips saw Buehman spends weeks at a time with local tribes or photographing various places of interest in southern Arizona.[23] Motivation for these trips was primarily commercial instead of artistic. As his portfolio of images grew he made deals with dime novel publishers and sold copies directly to the public. Buehman's images were also used as part of a "Sell Arizona" campaign.[15] By the 1893 Chicago World's Fair his catalog of images available for purchase included 10,000 photographs of Native Americans.[24]

While his images cover a wide variety of subjects, children were Buehman's favorite subject.[20] Beginning in 1890, he began using the images of the faces of children to produce a series of photographic collages. His first collage, named Arizona Bonanza, contained the faces of 433 children and sold for 25¢ a copy. While probably intended primarily for mothers, the back of the card had verses printed upon it claiming the children were Arizona's greatest treasure.[25] Globe and Globules followed the next year with the first version of Buehman's Babies appearing in 1892.[20] Buehman's Babies underwent several revisions with the final version being made in 1911.[25] Containing the faces of 2551 children, the work was praised by Buehman's professional brethren.[12] Following his death, the original Buehman's Babies was inadvertently discarded before being located and recovered by Buehman's son, Albert.[26]

His professional accomplishments gave Buehman the recognition to excel in politics and civic affairs. When the railroad reached Tucson, Buehman was a member of the official welcoming committee.[27] He served as secretary of Board of Trustees of Tucson and was elected Public Administrator for Pima County in 1882.[1] In 1890, he served a one-year term as county assessor.[1][27] Finally, Buehman was Mayor of Tucson from January 1895 till January 1899.[2] As mayor he worked for improvements of sidewalks and streets and oversaw the City of Tucson's efforts to purchase the local waterworks.[1] Buehman's other accomplishments as mayor include a law prohibiting cockfights and similar blood sports, the planting of shade trees, and the westward expansion of Congress street.[27]

Socially, Buehman was a Master Mason and member of the Ancient Order of United Workmen.[28] While raised a Lutheran, he was a member of the First Congregational church of Tucson where he served as a senior deacon.[28] Buehman married Estelle Morehouse of Portland, Michigan in October 1882.[3] The union produced two sons: Willis and Albert.[12]

Buehman died from pneumonia on December 19, 1912.[28] Following his death, Tucson acquired approximately 65,000 negatives showing the city's people and surrounding areas.[29] After his death, Buehman's son Albert assumed control of Buehman Studio until his retirement in 1949. Albert's son Remick then took over the studio before selling it two years later.[30] Over 250,000 negatives produced by three generations of Buehmans were purchased by the Arizona Historical Society in 1967. [21] Buehman Canyon in the Santa Catalina mountains is named in his honor.[31]

Footnotes

- Various sources show Buehman worked in San Francisco for a period of between one and two years.[3][5]

- Various sources give different names for the Mexican photographer.[1][7]

- It is unclear if Buehman had any formal training as a dentist. This was true of many dentists in the American West during the 1870s. It is also unclear how often Buehman worked as a dentist.[7]

References

- Moore 1960, p. 10.

- Chapman Publishing Co. 1901, p. 985.

- McClintock 1916, p. 830.

- Evans 1981, p. 61.

- Cooper 1989, p. 251.

- Daniels 1968, p. 182.

- Cooper 1989, p. 252.

- Cooper 1989, pp. 252–3.

- Evans 1981, p. 62.

- Cooper 1989, p. 256.

- Cooper 1989, p. 253.

- Chapman Publishing Co. 1901, p. 986.

- Cooper 1989, p. 254.

- Daniels 1968, pp. 188–9.

- Cooper 1989, p. 255.

- Cox, Larry (September 25, 2003). "Images of Death". Tucson Citizen.

- Evans 1981, p. 67.

- Evans 1981, p. 69.

- Cooper 1989, pp. 254–5.

- Cooper 1989, p. 261.

- Allen, Paul L. (November 1, 1995). "Picture Perfect". Tucson Citizen.

- Daniels 1968, p. 188.

- Moore 1960, p. 11.

- Cooper 1989, pp. 255–6.

- Evans 1981, p. 65.

- Evans 1981, pp. 65–7.

- Evans 1981, p. 80.

- McClintock 1916, p. 835.

- Evans 1981, p. 59.

- Allen, Paul L. (August 22, 2002). "Photo exhibit highlights Buehman family works". Tucson Citizen.

- Cooper 1989, p. 258.

- Portrait and biographical record of Arizona. Chicago: Chapman Publishing Co. 1901. p. 985. OCLC 247520194.

- Cooper, Evelyn S. (Autumn 1989). "The Buehmans of Tucson: A Family Tradition in Arizona Photography". The Journal of Arizona History. Arizona Historical Society. 30 (3): 251–278. ISSN 0021-9053. JSTOR 41695764.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daniels, David (Winter 1968). "Photography's Wet-Plate Interlude in Arizona Territory: 1864–1880". The Journal of Arizona History. Arizona Historical Society. 9 (4): 171–194. ISSN 0021-9053. JSTOR 41695493.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Susan (January 1981). "Henry Buehman, Tucson photographer 1874–1912". History of Photography. Taylor & Francis. 5 (1): 59–81. doi:10.1080/03087298.1981.10442634. ISSN 0308-7298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McClintock, James H. (1916). Arizona, Prehistoric, Aboriginal, Pioneer, Modern: The Nation's Youngest Commonwealth Within a Land of Ancient Culture. Volume III. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. OCLC 5398889.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Yndia Smalley (Fall 1960). "Henry Buehman". Arizoniana. Arizona Historical Society. 1 (3): 10–11. ISSN 0883-346X. JSTOR 41700485.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)