Henry Breault

Henry Breault (14 October 1900 – 5 December 1941) was a United States Navy submarine sailor who received the Medal of Honor for his actions while serving aboard the submarine USS O-5 (SS-66). He was the first submariner[1] and he remains the only enlisted submariner to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions aboard a United States submarine.[2]

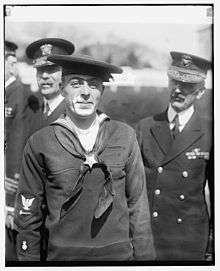

Henry Breault | |

|---|---|

Henry Breault | |

| Born | 14 October 1900 Putnam, Connecticut |

| Died | 5 December 1941 (aged 41) Newport, Rhode Island |

| Place of burial | Saint Mary Cemetery Putnam, Connecticut |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | Royal Navy United States Navy |

| Years of service | ca. 1916 – ca. 1920 (Royal Navy) ca. 1921 – 1941 (U.S. Navy) |

| Rank | Torpedoman Second Class (U.S. Navy) |

| Unit | USS O-5 (SS-66) |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

Biography

Henry Breault was born in Putnam, Connecticut, on 14 October 1900. During World War I he enlisted in the British Royal Navy at sixteen years of age and, after serving under the White Ensign for four years, joined the U.S. Navy.[3]

On 28 October 1923, Torpedoman Second Class Breault was a member of the crew of USS O-5 (SS-66) when that submarine was sunk in a collision in the Panama Canal. Though he could have escaped, Breault chose to assist a shipmate and remained inside the sunken submarine until both were rescued more than a day later. For his "heroism and devotion to duty" on this occasion, Henry Breault was awarded the Medal of Honor. He received his Medal of Honor from President Calvin Coolidge, in ceremonies at the White House, Washington, D.C., on 8 March 1924.[3]

Following twenty years of U.S. Navy service, Henry Breault became ill with a heart condition. He died at the Naval Hospital at Newport, Rhode Island, on 5 December 1941, two days before the attack on Pearl Harbor brought on U.S. entry into World War II. He was buried in Saint Mary Cemetery in Putnam, Connecticut.[3]

Petty Officer Breault was the first submariner to receive the Medal of Honor and the only enlisted man to receive the Medal of Honor for heroism while serving as a submariner. Seven submarine commanders received the Medal of Honor during World War II. Master Chief Petty Officer William R. Charette received the Medal of Honor for heroism while a Navy corpsman during the Korean War and later joined the submarine service.

Medal of Honor action

On 28 October 1923, the USS O-5 (SS-66) was operating with other units of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet under the command of Commander Submarine Force, Coco Solo, Canal Zone. At approximately 0630, USS O-5, under the command of Lieutenant Harrison Avery, was underway leading a column of submarines consisting of O-5, O-3 (SS-64), O-6 (SS-67), and O-8 (SS-69) across Limon Bay toward the entrance to the Panama Canal. The steamship SS Abangarez, owned by the United Fruit Company and captained by Master W.A. Card, was underway toward Dock No. 6 at Cristobal. Through a series of maneuvering errors and miscommunication, the SS Abangarez collided with O-5 and struck the submarine on the starboard side of the control room, opening a hole some ten feet long and penetrating the number one main ballast tank. The submarine rolled sharply to port – then back to starboard – and sank bow first in 42 feet (13 m) of water.[2]

The steamship picked up eight survivors – including the commanding officer – who had either been topside or climbed up quickly through the conning tower hatch. Nearby tugs and ships rescued several others. Eight minutes after O-5 sank, Chief Machinist’s Mate C.R. Butler surfaced in an air bubble. In all, 16 crewmen were rescued. Five were missing: Chief Electrician’s Mate Lawrence T. Brown, Torpedoman’s Mate Second Class Henry Breault, plus three others.[lower-alpha 1][2]

Henry Breault had been working in the torpedo room when the collision occurred, and he headed up the ladder topside. As he gained the main deck, he realized that Chief Brown was asleep below. Instead of going over the side, Breault headed back below to get Brown and shut the deck hatch over his head just as the bow went under. Brown was awake, but unaware of the order to abandon ship. Both men headed aft to exit through Control, but the water coming into the Forward Battery compartment made that escape route unusable. They made it through the rising water to the torpedo room and had just shut and dogged the door when the battery shorted and exploded. Breault knew the bow was under, and they were trapped.[2]

Salvage efforts began immediately, and divers were sent down from a salvage tug that arrived from Coco Solo. By 10:00 am, they were on the bottom examining the wreck. To search for trapped personnel, they hammered on the hull near the aft end of the ship and worked forward. Upon reaching the torpedo room, they heard answering hammer blows from inside the boat. In those days before modern safety and rescue devices, the only way the salvage crew, under the command of Captain Amos Bronson, Jr., could get the men out of the boat was to lift it physically from the mud using cranes or pontoons. There were no pontoons within 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of the site, but two of the largest crane barges in the world, Ajax and Hercules, were in the Canal Zone. They had been built specifically for handling the gates of the canal locks. However, there had been a landslide at the famous Gaillard Cut, and both barges were on the other side of the slide, assisting in clearing the Canal. The excavation shifted into high gear and by 2:00 pm on the afternoon of the sinking, the crane barge Ajax squeezed through and was on its way to the O-5 site.[2]

Divers worked to tunnel under O-5’s bow so lifting cables could be attached. Ajax arrived about midnight, and by early morning, the cable tunnel had been dug, the cable run, and a lift was attempted. Sheppard J. Shreaves, supervisor of the Panama Canal’s salvage crew and himself a qualified diver, had been working continuously throughout the night to dig the tunnel, snake the cable under the submarine, and hook it to Ajax’s hoist. Now the lift began. As the crane took a strain, the lift cables broke. Shreaves and his crew worked another cable set under the bow and again Ajax pulled. Again, the cable broke. All through the day, the men worked. Shreaves had been in his diving suit nearly 24 hours. As midnight on 29 October approached, the crane was ready for another lift, this time with buoyancy being added by blowing water out of the flooded Engine Room. Then, just after midnight, the bow of O-5 broke the surface. Men from the salvage force quickly opened the torpedo room hatch, and Breault and Brown emerged into the fresh air.[2][lower-alpha 2]

Brown's account

Breault and I separated to pound on each of the boat’s sides. In this way, the rescuers would know that there were two of us. Breault played a kind of tune with his hammer, indicating to the diver that we were in good shape and cheerful. Neither of us knew Morse Code. We had no food or water, and only a flashlight. We were confident we could stay alive for forty-eight hours. …The high pressure and foul air gave us severe headaches. We did very little moving or talking; it excited our hearts too much. …We heard scraping on the hull for hours. A couple of times we felt the O-5 being lifted, and then we got tossed roughly when the slings broke. We knew they were hard after us. This buoyed our hopes for rescue tremendously. …Finally, the sub began to be tilted upward slowly. We felt we would escape this time, but it seemed like forever. The last 20 minutes were unbearable. We heard our comrades walking on deck. Breault opened the hatch and we could see daylight. We were saved!!![4]

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and organization: Torpedoman Second Class, U.S. Navy. Born: 14 October 1900, Putnam, Conn. Accredited to: Vermont. G.O. No.: 125, 20 February 1924.

Citation:

- For heroism and devotion to duty while serving on board the U.S. submarine O-5 at the time of the sinking of that vessel. On the morning of 28 October 1923, the O-5 collided with the steamship Abangarez and sank in less than a minute. When the collision occurred, Breault was in the torpedo room. Upon reaching the hatch, he saw that the boat was rapidly sinking. Instead of jumping overboard to save his own life, he returned to the torpedo room to the rescue of a shipmate whom he knew was trapped in the boat, closing the torpedo room hatch on himself. Breault and Brown remained trapped in this compartment until rescued by the salvage party 31 hours later.[5]

For his role in the rescue, Sheppard Shreaves later received the Congressional Life Saving Medal, presented personally by Breault and Brown that same year.[2]

Awards

- Medal of Honor

- Navy Good Conduct Medal

- American Defense Service Medal

- British War Medal (United Kingdom)

- Victory Medal (United Kingdom)

See also

- List of Medal of Honor recipients

- List of Medal of Honor recipients in non-combat incidents

- "Henry Breault". Claim to Fame: Medal of Honor recipients. Find a Grave. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

Notes

- Motor Machinist’s Mate First Class Clyde E. Hughes, Mess Attendant First Class Fred C. Smith, Fireman First Class Thomas T. Metzler were the other missing sailors.

- Two of the other missing men’s bodies were recovered from alongside the boat and interred at the Mount Hope Cemetery in the Canal Zone. Petty Officer Clyde E. Hughes’ body was never found.

Citations

- Owens, Ronald J. (2004). Medal of Honor: Historical Facts & Figures. Turner Publishing Company. p. 18. ISBN 1563119951. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Christley, Jim. "Submarine Hero: TM2 Henry Breault". Undersea Warfare Spring 1999 Vol. 1, No. 3. Chief of Naval Operations Submarine Warfare Division. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "US People – Breault, Henry". US Navy Heritage & History Command. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Grigore (February 1972) pp. 54-60.

- "Medal of Honor Recipients – Interim Awards, 1920–1940". United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

References