Henry Alline

Henry Alline (pronounced Allen) (June 14, 1748 – February 2, 1784) minister, evangelist, and writer, who became known as "The Apostle of Nova Scotia". Born at Newport, Rhode Island. He became a New England Planter and served as an itinerant preacher throughout Maritime Canada and Northeastern New England from 1776 to 1784. His ministry coincided with the second Great Awakening period and he became the leader of the New Light movement in the Maritimes.[1] Later in life he caught the attention of renowned theologian John Wesley. Alline is Canada's most prolific Eighteenth-century writer. His Journal is considered a classic of North American spiritualism and he is Canada's first great Protestant and one of its most important theological writers. He died at age 35 and is buried at North Hampton, New Hampshire.

Historical context

The period of the early 1740s to 1784 was one of a struggle for hegemony of North America by Britain, significant religious upheaval in northeastern North America, and ultimately revolution in the Thirteen Colonies.

War and revolution

Just prior to Alline's birth the War of the Austrian Succession had just come to a close with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748). Northeastern North America had been pulled into the conflict (see King George's War ); achieving a significant victory with the capture of the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1745, only to have it returned, to the chagrin of New England, to France during Treaty negotiations. Over the next seven years a peace rested uneasily between Britain and France. By the mid-1750s conflict broke out again resulting in the Seven Years' War. Nova Scotia's population was decimated with the deportation of the Acadians.

With the removal of the common enemy, France, in North America a paradigm shift occurred in the political relationship between the British Metropole and its New World colonies. The deteriorating relationship in due course resulted in the American Declaration of Independence and Revolutionary War.

Religious upheaval

Almost coinciding with these aforementioned periods of war was the rise of the First and Second Great Awakening religious revivals.

The First Great Awakening period occurred over the twenty years running up to 1750. With its initial roots in England it spread to and flourished in the Thirteen Colonies. Under the Awakening evangelical ministers came to the fore with their sermons and teachings that elicited an emotional response over the intellectual. Church gatherings became more participatory; moving to a development of more democratic churches. The Awakening, although affecting a broad cross section of American society at the time, had its greatest influence on church leaders, the educated and the elite. It is thought the democratizing ways of the movement influenced the populace; leading them eventually to throw off their colonial shackles. As a result of the hard times of the 1760s and early 1770s, the settlers found it difficult to put their religious life on an organized, institutional basis, and since it cost money to build churches and pay ministers, the settlers were hard pressed to meet such obligations.[2]

The Second Great Awakening began in the last quarter of the Eighteenth Century, with its influence still felt into the 1840s. (Many current day churches, including the Mormons (LDS Church), developed in the later part of this period.) This second period of evangelicalism heavily influenced the mid to lower levels of society. The movement generally advocated the individual can and must have a direct relationship with God and that all people were able to be saved. For those people living in New England this was counter to their Calvinism with its idea that only a preordained elected few would be saved. The Awakening's new ideas caused the new born faithful (New Lights) to shun vices and evil pastimes to live more personally within the Christian ethic.

Early life

Henry was born in Newport, Rhode Island, the second child of eight, to William Alline and Rebeccah Clark. Here he lived and attended school until the age of twelve. By his own account he was an advanced student. His religious education began at this time, receiving instruction at school, within the church, as well as at home. At about the age of eight he appears to have had his first religious experience, although not fully aware of its nature at the time. The event placed him in a state of terror and drove him to seek out a fuller understanding of Christian theology.

After the deportation of the Acadians, Nova Scotia's fine farmlands in the Bay of Fundy region remained empty and in an effort to repopulate the country the British government offered the recently vacated lands in grant to Protestants who wished to move to the colony. William Alline took up the offer and arrived in the fall of 1760, taking up his land grant in Falmouth, Nova Scotia. With the family's move Henry's formal education came to an end.

Life in the new land was hard and uncertain. They had left behind a vibrant town and warm comfortable home to replace it with a tent and food shortages. The new Planter townships lacked churches, schools and other infrastructure familiar in the towns they had left behind in New England. The townships remained isolated, connected to the outside world by narrow paths through the forest and ships along the coast. For the first few years, as Britain and France remained at war, threats of attack by France's allies, the Mi'kmaq, remained a possibility. The government in Halifax also soon began to break its promises. The Planters had initially been promised their township governance model would be allowed in the new colony but this was soon overturned for a centralized governance model based in Halifax. This created a minor crisis but was overshadowed by the need to build new homes and farms which would support the Planters' families. Town assemblies of a sort continued until 1770 when they were finally forbidden due the sympathetic position emanating from these gatherings for the rebels in the more southerly colonies. As a young man by this time Alline is likely to have participated in the assemblies. This along with other factors would lead the Planters to question where their loyalties lay – with the British or their brethren in the Thirteen Colonies.

Alline appears to have been a product of his time over this period up to 1776. He lived and worked on the family farm and as his siblings came to maturity they moved to their own farms but he stayed on, supporting his parents, and never marrying. As the second of only two sons this was his obligation. In his Journal he reports participating in the favorite pastime of the youths of the day of frolicking, which included dancing, partying, drinking, etc. Alline admits to being one of the ringleaders of these raucous activities. Despite his leadership in the frolicks he wrestled with his participation, feeling it was perhaps a debauched life and contrary to finding a path to a more godly life. In his words he stated "... I felt guilty as ever, and sometimes could not close my eyes for hours after I had got home to my bed, on account of the guilt I had contracted the evening before. O what snares were these frolicks and young company to my soul, and had God not been more merciful to me than I was to myself, they would have proved my fatal and irrevocable ruin."[3]

Alline's second religious experience came when he was about twenty. He experienced a vision where he was "surrounded by an uncommon light; it seemed like a blaze of fire; I thought it out shone the sun at noon day...". He further went on to say "The first conception I had was that the great day of judgment was come..." The vision remained over him for some time and then "when I lifted my eyes, I saw, to my unspeakable satisfaction, that it was not what I expected: the day was not really come, therefore I had an opportunity of repentance ..."[4] Despite his second religious experience he continued to backslide into his old ways, all the time continuing to struggle with this predicament.

Although Alline's formal education came to an end at the age of twelve it is clear his thirst for knowledge continued. He was self-taught and when able to find texts he studied them thoroughly. His reading was extensive, having studied works by William Law, John Fletcher, Edward Young, John Milton, Alexander Pope, John Pomfret, Isaac Watts, Martin Luther, John Bunyan, John Edwards, Increase & Samuel Mather, and perhaps even Jacob Boehme. His studies had brought him to a point where he "had read, studied and disputed too much, that I had acquired a great theory of religion ..."[5][6]

At the age of twenty-eight he had his third religious experience; the one that would turn his life around and propel him into his evangelical ministry. Unlike the previous experiences which instilled terror within his soul this experience felt like "his redeeming love broke into my soul with repeated scriptures with such power, that my whole soul seemed to be melted down with love". At this time he became committed to preaching the gospel.

Ministry

Alline immediately revealed his rebirth experience to his parents, which they initially welcomed. With his announcement of his need and desire to spread the gospel, he came into conflict with them. At this time, Alline's parents were in the sunset of their lives and depended on Henry's management of the family farm for their welfare. More importantly though they recognized, as did Alline, that under the traditional Congregational churches only appropriately educated and ordained ministers were eligible to preach. This weighed heavily on Alline who, in short order, attempted to sail to New England to seek the appropriate education and training. This was on the eve of the American Revolution and the violent convulsions that began to occur in New England precluded his departure from Nova Scotia.

Despite his misgivings he began preaching in Falmouth, particularly after his neighbors heard he had become a New Light and sought his advice and asked him to lead them in prayer. This again brought him at odds with his parents. They were known to walk out of churches where he began to preach. In 1776 he began preaching at Newport, the township adjacent to Falmouth. His reputation as a gifted spiritual speaker spread and soon crowds were flocking to Falmouth to hear him. That same year, both Falmouth and Newport formed churches with his assistance. These churches were anti-Calvinist in nature and generally rejected traditional Congregationalism. By 1777, Alline finally broke from his parents and pursues his evangelical ministry on a full-time basis. In 1778 the Horton/Cornwallis townships sought his assistance to establish a Baptist church. This church was the first Baptist Church in Canada (see Baptists in Canada). The following year this Church along with the Falmouth and Newport Newlight churches ordained him. This act removed one of Alline's perceived impediments to his right to preach. Despite Alline's assistance in establishing the Horton/Cornwallis Baptist church, because of a dispute concerning the proper mode of baptism, it denied him fellowship.

Until 1783 Alline travelled extensively throughout the Planter settled areas of Nova Scotia, the Saint John River Valley, and the Chignecto area. His effort to reach the people was Herculean, travelling mostly by foot and at times on horseback to reach every possible hamlet. His ministry was hugely successful, drawing the attention and grudging admiration of even those who opposed him such as Simeon Perkins of Liverpool who stated "Never did I behold Such an Appearance of the Spirit of God moving upon the people ... Since the time of the Great Religious Stir in New England many years ago."[7] By 1783, even Alline's opponents acknowledged that the whole colony outside of Halifax had come under Alline's revivalist influence.[8] Despite his success, he was not accepted by all he encountered. Opposition rose against him from those who thought he was a destabilizing factor to the social order of the day - primarily government representatives in Halifax, as well as the Anglican clergy who were fully integrated into the governmental power structure. Ministers of various other Protestant sects also opposed him on theological grounds, the Newlight's jettisoning of an educated and 'properly' ordained ministry, and assuredly the loss of parishioners which eroded both tithing flows and the clergy's status within their community hierarchy. A significant result of the revival was that it stimulated much more frequent inter-settlement contact, as Alline travelled where none had gone before.[9]

Throughout this period Alline established seven additional churches and composed his many hymns, pamphlets, sermons, personal Journal, and two major theological works. The frantic pace which Alline imposed upon himself weakened his health and allowed the rapid advance of tuberculosis. Even so, in 1783 he decided to travel to New England to spread his Newlight ideas to his former brethren. His ministry there lasted until February 1784 when he finally succumbed to his illness.

Death

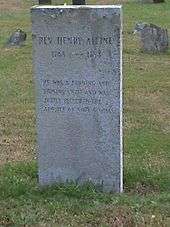

Alline fell mortally ill the last week of January 1784, while preaching at North Hampton, New Hampshire. The Reverend David McClure, a Calvinist minister, and his family took him into their home and provided him with whatever comforts they could extend to a dying man. On February 2, he died of complications arising from tuberculosis. McClure and his Church arranged for Alline's burial in their own church burying ground. The epitaph they had cut into his tombstone reads "He was a burning and shining Light, and was justly esteemed the apostle of Nova Scotia."[10][11]

Theology

Alline's Newlight ideas moved away from, but did not fully abandon its Congregationalist antecedents. Although he was anti-Calvinist on many points he sought a renewal of the belief moving it back to the church of earlier times. The Congregationalist church had by the early eighteenth century become the 'established' religion of New England, enjoying its position and perks within society, and generally hardened its position with regard to the preordained few. It "had lost its lay orientation and spiritual radicalism"[12] The church needed to be returned to the people and thus Alline moved to find the church's earlier, purer form. He rejected the power structures in the church, its idea of predestination, and many of its traditions and ceremonial practices. He may have been "The first North American evangelical to argue the case against predestination.."[13] The new teaching revealed that all people have free will and therefore can be reborn into a personal relationship with God. He portrayed an eternally loving God was waiting for those chose to take the right path. These ideas were heavily influenced by earlier writers such as William Law (see Early life).

Alline wrote and espoused many sound ideas whereas others moved into the realm of mysticism and some were simply convoluted. He taught that the souls of all humankind are emanations from the same Spirit, that these spirits along with the Angels had lived in a paradise with God. Furthermore, that Adam and Eve existed as one combined spirit. It was after the fall from heaven that Adam and humankind took on corporeal form and as a group participated in original sin. He further stated that all time; past, present and future, occur instantaneously and once the time of judgement comes we will all remember our participation in the act of original sin.

John Wesley was sent Alline's 'Two Mites Cast into the Offering of God, for the Benefit of Mankind' by the Nova Scotia Methodist leader William Black. Wesley concluded Alline theology contained both "gold and dross" and further with respect to Alline's last section of 'Mites' dealing with metaphysical mysticism "is very far from being a man of sound understanding; but he has been dabbling in Mystical writers, in matters which are too high for him, far above his comprehension. I dare not waste my time upon such miserable jargon[14]

The success of Alline's theology in part clearly arose from his charismatic personality and oratorical gift which drew people to his cause. Beyond this he was able to speak to the Planter populace's spiritual and political lives. The Planters had fallen into a melancholy due to their isolation on a colonial frontier and being marginalised in the conflict arising in Nova Scotia's sister colonies. Their Calvinism was based on a fear of God and damnation. This could only create anxiety for the greater part of believers as they would never achieve salvation as only the few were preordained to achieve this reunion with God. Few preachers were available to the Planters. Alline's very own township had not been able to attract a minister into its midst. This lack of guidance could have only left the Planter's in a spiritual vacuum. The troubles in the Thirteen Colonies further compounded the Planters confusion and fellings of aimlessness, leaving them in an awkward position with respect to both their former neighbours in New England and with the British authorities in Halifax.

With Alline's theology based on the eternal love of God and the ability of all people; male or female, high or low born, to achieve salvation a path forward was perhaps available. This new radical idea instilled in the Planters a new feeling of identity and security. It pointed the way out of their spiritual malaise and showed them a path whereby they could achieve a nonconformist loyalty to the British authority yet still be viewed by their New England neighbours as standing apart from the British. By default they had found a neutrality of sorts and also began the process of creating a Maritime identity.

Legacy

Though he made many converts to his religious ideas the Allinites splintered into many competing Newlight sects after his death. Some of these were Pansonites, Chipmanites, Kinsmanites, Blackites, Welshites, Hammonites, Palmerites, Brookites, Pearlyites and Burpeites, and a few even turned to the Anabaptist belief.[15] Most of these sects disappeared as quickly as they appeared, with the followers eventually merging with either Wesleyan, Congregationalist churches or helping establish two major Baptist denominations in the Maritime region. This legacy has made the Maritime region the Baptist bastion of Canada.

In America his theology was a key generative factor in the birth of New England's Free Will Baptist churches.

Alline is Canada's most prolific Eighteenth-century writer, publishing 487 hymns & spiritual songs, three sermons, many pamphlets, as well as two major theological works - 'Two Mites Cast into the Offering of God, for the Benefit of Mankind' and 'A Court for the Trial of the Anti-Traditionalist'[16] His Journal was published posthumously, and has now taken its place as one of the classics of North American spiritualism and Christian mysticism.[17] In spite of being voluminous, Alline's journal is of limited utility, "his profuse and repetitive style often becomes little more than a list of the places he visited and a continual restatement of his spiritual travails."[18]

See also

- Rev. Freeborn Garrettson

- Rev. John Payzant

Further reading

- Henry Alline: Problems of Approach and Reading the Hyms as Poetry. by Thomas Vincent, Department of English, Royal Military College, Kingston.

- Stewart, Gordon. Documents Relating to the Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1760-1791. Toronto: Champlain Society Publications, 1982.

References

- Rawlyk (1986)

- Stewart, Gordon T., ed. (1982). Documents Relating to the Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1760–1791. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 21.

- Beverley & Moody (1982), p. 39

- Beverley & Moody (1982), pp. 47–48

- Beverley & Moody (1982), p. 46

- Bumstead (1984)

- Bell (1993), p. 10

- Stewart, Gordon T., ed. (1982). Documents Relating to the Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1760–1791. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 11.

- Stewart, Gordon T., ed. (1982). Documents Relating to the Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1760–1791. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 17.

- Bumstead (1984), p. 85

- Julian (1907), p. 51

- Bell (1993), p. 5

- Bell (1993), p. 18

- Bumstead (1984), p. 77

- Bell (1993), p. 19

- Beverley & Moody (1982), pp. 15–16

- Alline (1806)

- Stewart, Gordon T., ed. (1982). Documents Relating to the Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1760–1791. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 13.

Bibliography

- Alline, Henry (1806). The Journal of the Rev. Mr. Henry Alline. Boston: Gilbert & Dean.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bell, D. G. (1993). Henry Alline and Maritime Religion. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beverley, James; Moody, Barry, eds. (1982). The Journal of Henry Alline. Wolfville, NS: Lancelot Press for the Baptist Heritage in Atlantic Canada, Acadia Divinity College and the Baptist Historical Committee.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bumstead, J. M. (1984). Henry Alline. Hantsport, NS: Lancelot Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Julian, John (1907). A Dictionary of Hymnology. London: John Murray.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rawlyk, George A., ed. (1986). The Sermons of Henry Alline. Hantsport, NS: Lancelot Press for Acadia Divinity College and the Baptist Historical Committee of the United Baptist Convention of the Atlantic Provinces.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- The Life and Journal of the Rev. Mr. Henry Alline Boston: Gilbert & Dean, 1806.

- Bumsted, J. M. (1979–2016). "Alline, Henry". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Revival Library. "Henry Alline - 1748-1784". Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- Julian, John (June, 1907). A Dictionary of Hymnology. London: John Murray

- Lochhead, Douglas. "Alline, Henry". Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- The New Light Experience of Henry Alline. Video by Redstar Films Limited.