Helsinki–Tallinn Tunnel

The Helsinki to Tallinn Tunnel is a proposed rail undersea tunnel that would span the Gulf of Finland and connect the Finnish and Estonian capitals. [1] The tunnel's length would depend upon the route taken; the shortest distance across would have a submarine length of 50 kilometres (30 mi), making it the longest undersea tunnel in the world (both the Channel Tunnel and Seikan Tunnel, whilst longer, have less length undersea). The tunnel, if constructed, is estimated to cost €9–13 billion and would open sometime after 2030. The European Union has approved €3.1 million in funding for feasibility studies.[2]

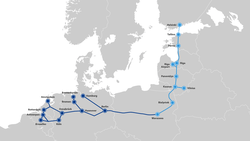

A map of the assessed tunnel routes between Tallinn and Helsinki | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea) |

| Status | Planned |

| Start | Ülemiste, Estonia |

| End | Pasila, Helsinki, Finland |

| Technical | |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) (standard gauge) |

Background

Helsinki and Tallinn are separated by the Gulf of Finland. The distance between the cities is about 80 kilometres (50 mi). Travel between the capitals is currently mainly by ferry and fast passenger boat, travel time varying from 1 hour 40 minutes (fast summer ferries operating from April to October) to three and a half hours (normal ferries operating year-round), but most ferries now take two hours per trip. Some eight million trips are made by ferry each year, including both leisure cruises and scheduled commuter service. Overland travel between Helsinki and Tallinn requires an 800-kilometre (500 mi) journey through Russia.[3] There are also around 300,000 air trips done per year between the cities.

Project status

Both cities have promised €100,000 for preparatory studies, though the relevant ministries of each country have refused to grant any funding. An application is now planned to the EU to gain the additional funds needed for a comprehensive survey, estimated to cost between €500,000 and €800,000.[4] On 13 January 2009, newspaper reports suggested the application to the EU, through the Interreg programme, for comprehensive surveys had been denied. An expert at the City of Helsinki's International Affairs department suggested this may have been because of political tension within Estonia, between the national administration and the City of Tallinn, both controlled by rival political groups. Nevertheless, both cities are said to be considering funding the surveys themselves.[5]

On 2 April 2014, it was announced that a €100,000 preparatory survey named TalsinkiFix will assess whether a more comprehensive profitability calculation should be done. The European Union will cover 85 per cent of the survey costs and the cities of Helsinki and Tallinn and the Harju County will pay the rest. This is the first official survey about the tunnel.[6]

The results of the preparatory survey were released in February 2015.[7] The cost of the tunnel was estimated to be €9–13 billion and the tunnel could open at earliest after 2030. The survey recommended the tunnel to be built for railway connections only with the traveling time between Helsinki and Tallinn being half an hour by train.[8]

On 4 January 2016, it was announced that the transport ministers of Finland and Estonia as well as the leadership of the cities of Helsinki and Tallinn will sign a memorandum on traffic cooperation between the two countries, including a further study to examine the feasibility of the tunnel. This study is the first to be conducted on the state level and will focus on the tunnel's socio-economical effects and geological analysis. Finland and Estonia are asking financial support from the EU for the study.[9] In June 2016, the EU granted €1 million for the study which is expected to be ready in early 2018.[10]

In August 2016 a two-year study was launched by the Helsinki-Uusimaa Regional Council. Other partners in the study are the government of Harju County, the cities of Helsinki and Tallinn, the Finnish Transport Agency and the Estonian Ministry of Transport and Communications. The project is headed by Kari Ruohonen, the former director general of the Finnish Transport Agency.[11]

In February 2017 two consortia were commissioned to study aspects of the project. One will study passenger and freight volumes and do a cost-benefit analysis. The other will study the technical aspects of the project.[12]

In March 2019 a similar project by Peter Vesterbacka has moved forward. Vesterbacka has made a tentative deal with Chinese investment company called Touchstone Capital Partners.[13] The deal consists of memorandum of understanding for a 15 billion euros financial deal to fund 4 stations, the tunnel and the trains.

Cost and benefits

The cost of the tunnel connection has been tentatively estimated to be €9–13 billion. This includes €3 billion for the tunnel excavation, €2–3 billion for infrastructure and security systems, over €1 billion for rolling stock and other equipment and €1–3 billion risk marginal for unexpected situations. The project is estimated to be financially feasible if the European Union covers at least 40 per cent of the cost, the rest being shared by Finland and Estonia and the two capital cities (for comparison, the Rail Baltica project has received 85 per cent of its funding from the EU).[14]

The economic benefits would be significant, both in terms of increased connections and economic integration between the two cities (the Øresund Region has been offered as an example), but also in a wider context of convenient passenger train connections between Southern Finland and the Baltic states, and a fixed link for freight from across Finland on to the Rail Baltica, thus providing a rail freight connection with the rest of Europe. An estimated 12.5 million annual passengers would use the tunnel.[15]

Geopolitically, the tunnel would connect two close but separated parts of the European Union in an environmentally friendly way, removing the need to use sea or air transport, or to travel through Russia. The Helsinki–Tallinn connection is part of the EU's TEN-T network's North Sea–Baltic corridor. The ports of Helsinki and Tallinn have previously received EU funding to improve transport conditions between the two cities.[16]

Technical details

Railways in Finland and Estonia use 1,524 mm (5 ft) track gauge. The Helsinki–Tallinn tunnel would according to current planning use European gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) tracks to connect directly to Rail Baltica which uses the same gauge. This means trains traveling through the tunnel from Tallinn to Helsinki could not continue onwards to other Finnish destinations and vice versa (apart from the Rail Baltica track) without new tracks being built or the use of a variable gauge system. Tentative plans have been made to build separate freight stations in Southern Finland (Riihimäki and Tampere have been suggested) which would make it possible to load trains outside Helsinki for transportation through the tunnel. Tampere and Helsinki Airport could also host passenger terminals for trains heading to Tallinn and onwards to Central Europe.[14][17]

Studies

- Usko Anttikoski. "Fixed transport connections across the Baltic from Finland to Sweden and Estonia. Preliminary feasibility assessment." 2007.

- "Emerald, Vision 2050" Greater Helsinki Vision 2050 – International Ideas Competition. 2007.

- Ilkka Vähäaho, Pekka Raudasmaa. "Feasibility Study, Helsinki–Tallinn, Railway Tunnel" Geotechnical Division of the Real Estate Department of the City Of Helsinki. 2008.

- Jaakko Blomberg, Gunnar Okk. "Opportunities for Cooperation between Estonia and Finland 2008" Prime Minister's Office, Finland. 2008.

See also

- Rail Baltica

- Rail transport in Estonia

- Rail transport in Finland

- Øresund Bridge

- Undersea tunnel

- Channel Tunnel

- Irish Sea Tunnel

- Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link – a planned immersed tunnel connecting Denmark and Germany

- Hyperloop[18][19]

References

- Mike Collier. "Helsinki mayor still believes in Tallinn tunnel", The Baltic Times, 3 April 2008. Retrieved on 2008-05-13.

- "Implementation of Helsinki-Tallinn tunnel to be studied with EU funding". 10 June 2013.

- Topham, Gwyn (6 January 2016). "Helsinki-Tallinn tunnel proposals look to bring cities closer than ever". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Helsinki-Tallinn Rail Tunnel Link?", YLE News, 28 March 2008. Retrieved on 2008-05-13.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kaja Kunnas (2 April 2014). "Junatunneli Helsingistä Tallinnaan maksaisi miljardeja euroja". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Pre-feasibility study of Helsinki–Tallinn fixed link (Sweco, february 2015)

- Moilanen, Anne (11 February 2015). "Esiselvitys: rautatietunneli Helsingin ja Tallinnan välille kannattaisi". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- "Helsinki–Tallinna-tunneli ottaa askeleen eteenpäin – Suomi ja Viro sopivat selvityksestä" (in Finnish). Helsingin Sanomat. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "EU provides 1 mln euros for Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel feasibility study". The Baltic Times. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "A vision of twin cities - study moves ahead on Helsinki-Tallinn tunnel". Yle Uutiset. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Helsinki–Tallinn tunnel feasibility studies commissioned". Railway Gazette. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "Helsinki-Tallinn tunnel to get $16.8 billion from Touchstone". Reuters. 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Sinervä, Jukka (5 January 2016). "A tunnel to Tallinn? Helsinki believes it's feasible". Yle. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "FinEst Link Project results: Helsinki–Tallinn railway tunnel to become an engine of regional growth". FinEst Link. 7 February 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Helsinki and Tallinn strengthen cooperation in mobility and transport". City of Helsinki. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Laita, Samuli (11 February 2015). "Helsingin johtajat haluavat jatkaa Tallinnan-tunnelihanketta". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- 7.6.2017 16:17, New Hyperloop plans could include Helsinki-Tallinn connection

- 20.02.2017 09:25, Hyperloop proponents interested in Helsinki-Tallinn undersea route

External links

- The FinEst Link – information about mobility between Helsinki and Tallinn, including the tunnel proposal

- Nov 13, 2018, 05:04am, Kayvan Nikjou, This Is The €15 Billion Tunnel Connecting Helsinki To Tallinn, forbes.com