Hell's Half Acre (Fort Worth)

Hell's Half Acre was a precinct of Fort Worth, Texas designated as a red-light district beginning the early to mid 1870s in the Old Wild West.[1] It came to be called the town's "Bloody Third ward" because of the violence and lawlessness in the area.[2]

| Hell's Half Acre (Fort Worth) | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Texas historical marker located at 12th and Houston street | |

| Location | Tarrant County, Texas |

| Nearest city | Fort Worth, Texas |

| Coordinates | 32°45′01″N 97°19′42″W |

| Area | .5 acres (0.20 ha) |

| Elevation | 610 feet (190 m) |

| Formed | 1870s |

| Governing body | State of Texas |

| Official name: Hell's Half Acre - Tarrant County - Fort Worth | |

| Designated | 1993 |

| Marker Number | 2431 |

| Atlas Number | 5439002431 |

Location within Texas | |

History

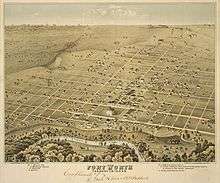

The area developed in the 1870s as a rest stop on the cattle trails from Texas through Kansas.[3] It quickly became populated with saloons, brothels, and other vice dens offering gambling, liquor, and prostitutes.[3] The half acre block was originally designated from tenth street to fifteenth street while intersecting with Houston street, Main street, and Rusk street with Throckmorton and Calhoun streets established as boundaries.[4] The Chisholm Trail and Texas and Pacific Railway were branded as the economic driving force leading to the progressive development of the rambunctious red-light district.[4]

At its peak, Hell's Half Acre consisted of boarding houses, bordellos, gambling parlours, hotels, saloons, and a sparse assortment of mercantile businesses.[5] It became a hide-out for thieves and violent criminals. The twenty-two thousand square foot ward caught the glimpse of such Old West personalities as Bat Masterson, Butch Cassidy, Doc Holliday, Etta Place, Luke Short, Sam Bass, Sundance Kid, and Wyatt Earp.[6] This led to crackdowns by law enforcement though they rarely interfered with the gambling and other vice operations in the area. The Acre was an important source of income for the town, and despite outside pressures against the illegal activities, Fort Worth officials were reluctant to take action.[3][4]

The city's most famous saloon was the White Elephant, technically located just outside of the Acre. The venue was known as much for its elegance and live entertainment as for its gun fights and often illegal dealings.[7]

The major complaints against the area within the community were primarily against the dance halls and brothels, which reformers saw as the most immoral, as well as the general violence. The saloons and gambling halls were generally less of a concern.[5] In 1889, following serious bouts of violence in the city, officials shut down many of the activities that were deemed as most directly contributing to the violence.[5] By the start of the 20th century, the Acre's popularity as a destination for out-of-town visitors had diminished dramatically.[3] The Progressive movement of the early 20th century put increasing pressure on the area. By 1919, Fort Worth's "Third Ward" was disavowed as a den of iniquity due to the law enforcement efforts of Jim Courtright and the Protestant orations of John Franklyn Norris.

See also

Notes

- "Sodom on the Trinity (Part 1): A Cold Day in Hell". Hometown by Handlebar. 10 June 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- McClure, Robin (17 September 2017). "This Hell's Half Acre In Fort Worth Has A Dark And Evil History That Will Never Be Forgotten". OnlyInYourState. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Selcer 2010

- Sault, Spring (3 May 2017). "Celebrating 150 Years of the Chisholm Trail: 'Hell's Half Acre', Fort Worth". Texas Hill Country. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Selcer 1991.

- Chanin, Joshua V. (19 October 2018). "Hell's Half Acre: Fort Worth's Dirty Secret". www.texasescapes.com. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Fort Worth's Wild White Elephant Saloon". History.net. June 12, 2006.

References

- Selcer, Richard F. (1991). Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red-Light District. Texas Christian University Press. ISBN 0875650880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Selcer, Richard F. (15 June 2010). "Hell's Half Acre, Fort Worth". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Hell's Half Acre - Fort Worth - Marker Number: 2431". Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Texas Historical Commission. 1993.