Hassan bin Rahma Al Qasimi

Hassan bin Rahma Al Qasimi was the Sheikh (ruler) of Ras Al Khaimah from 1814–1820. He was accused by the British of presiding over a number of acts of maritime piracy, an assertion he denied. Despite signing a treaty of peace with the British in October 1814, a punitive expeditionary force was mounted against Ras Al Khaimah in December 1819 and Hassan bin Rahma was removed as Sheikh of Ras Al Khaimah, which he ceded to the British in a preliminary agreement to the General Maritime Treaty of 1820.

| Hassan bin Rahma Al Qasimi | |

|---|---|

| Sheikh | |

| Ruler of Ras Al Khaimah | |

| Reign | 1814–1820 |

| Predecessor | Hasan bin `Ali Al Anezi |

| Successor | British Sultan Bin Saqr Al Qasimi as ruler of Sharjah and later Ras Al Khaimah |

| House | Al Qasimi |

Rule

The nephew of the Ruler of Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah, Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi,[1] Hassan bin Rahma emerged as the de facto Ruler of Ras Al Khaimah in 1814, although it is likely his rule started before this time.

He was a dependent of the ruler of the first Saudi state, Abdulla Ibn Saud (and his father Saud bin Abdulaziz before him). During a visit to Abdulla in Riyadh in August 1814, Hassan bin Rahma received a letter from the British Resident at Bushire accusing him of responsibility for the theft of two boats from Bombay laden with grain. The boats were apparently appropriated by six Al Qasimi boats off Karachi on 14 January 1814, although the British agent's letter asserts that Al Qasimi vessels had captured six or eight boats off the coasts of Karachi and Sind.[2]

Hassan denied the charges, pointing out that the Al Qasimi's boats did, indeed, travel to Sind where they traded. However, he also made a careful distinction between British subjects and native craft of Indian origin and denied capturing any boat with British passes and colours. This was accepted by the Bushire Resident, William Bruce.[3]

On 6 October 1814, an agreement was drawn up between Bruce and a representative of Hassan bin Rahma's, in which the Al Qasimi acquiesced to respecting vessels flying the British flag and assuring both British and Al Qasimi ships safe passage to the ports of Ras Al Khaimah and India. Al Qasimi ships would be distinguished by flying a red flag carrying the text 'There is but one God and Mohammed is his Prophet' in the middle.

Accusations of piracy

However, soon after the signature of the agreement, a British boat was seized as it visited Ras Al Khaimah with letters for Hassan bin Rahma from Bruce and the envoy had suffered 'the most degrading treatment.'[4] A series of incidents of 'piracy and plunder' then followed over the following four years, with the Al Qasimi laid firmly to blame by historian J. G. Lorimer, who asserted that the Al Qasimi "now indulged in a carnival of maritime lawlessness, to which even their own previous record presented no parallel".[5]

British accusations against the Al Qasimi at this time have been described as the result of a combination of acts of legitimate war by them against Muscat (with which they were at war) and confusion with Qatari pirate Rahma bin Jabir.[6] Whether the accusations were baseless, forming part of an attempt to curb Arab trade with India on the part of the East India Company (the argument put forward by Sultan bin Muhammad Al Qasimi in his Myth of Piracy in the Arabian Gulf) or a catalogue of piratical acts, the end result was the same. The British were resolved to move against Ras Al Khaimah.

In March 1819 Hassan bin Rahma went to the Ruler of Bahrain, Abdulla bin Ahmed, to mediate with the British and a release of prisoners (17 British subjects, all Indian women, were delivered to the British). His complaints to the British fell on deaf ears, as did his offer (of September 1819) to send three emissaries to negotiate a peace. Arriving at Bushire, the three representatives were turned back.[7]

The fall of Ras Al Khaimah

In November 1819, the British embarked on an expedition against Ras Al Khaimah, led by Major-General William Keir Grant, with a platoon of 3,000 soldiers. The British extended an offer to Said bin Sultan of Muscat in which he would be made ruler of the Pirate Coast if he agreed to assist the British in their expedition. Obligingly, he sent a force of 600 men and two ships.[8][9]

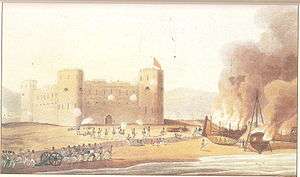

The force gathered off the coast of Ras Al Khaimah on 25 and 26 November and, on 2 and 3 December, troops were landed and, on 5 December, the town was bombarded from both land and sea. Continued bombardment took place over the following four days until, on the 9th, the fortress and town of Ras Al Khaimah were stormed. On the fall of Ras Al Khaimah, three cruisers were sent to blockade Rams to the North and this, too was found to be deserted and its inhabitants retired to the 'impregnable' hill-top fort of Dhayah.[10] The fort fell on 22 December.

The rout of Ras Al Khaimah led to only five British casualties as opposed to the 400 to 1000 casualties reportedly suffered by the Al Qasimi.[11]

The town of Ras Al Khaimah was blown up and a garrison was established there, consisting of 800 sepoys and artillery. The expedition then visited Jazirat Al Hamra, which was deserted, but then went on to destroy the fortifications and larger vessels of Umm Al Qawain, Ajman, Fasht, Sharjah, Abu Hail and Dubai. Ten vessels which had taken shelter in Bahrain were also destroyed.[12]

General Maritime Treaty

Defeated, Hassan bin Rahma gave himself up to the British and was imprisoned, but released when it was realised his imprisonment was widely unpopular.[13] He signed a preliminary agreement which ceded the town of Ras Al Khaimah and the area of Maharah to the British for use as a garrison.

The General Treaty for the Cessation of Plunder and Piracy by Land and Sea, dated 5 February 1820 was signed at variously at Ras Al Khaimah, Falayah Fort and Sharjah by the Sheikhs of Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al-Quwain and Ras Al Khaimah and the British.

Hassan bin Rahma signed the treaty as "Sheikh of 'Hatt and Falna', formerly of Ras Al Khaimah" ('Hatt' being the modern day village of Khatt and 'Falna' being the modern day suburb of Ras Al Khaimah, Fahlain near the location of Al Falayah Fort).

The treaty having been signed by William Keir Grant and all of the Trucial Rulers, the Government in Bombay made clear that it was most dissatisfied with his leniency over the coastal tribes and desired, 'if it were not too late, to introduce some conditions of greater stringency'. The release of Husain bin Ali, the Wahhabi leader and chief of Rams and Dhayah, was particularly regretted.[14]

Hassan bin Rahma was deposed in 1820[15] and Sheikh Sultan Bin Saqr Al Qasimi, Ruler of Sharjah, also became Ruler of Ras Al Khaimah.[16]

References

- 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. p. 168. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. p. 170. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. p. 173. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Lorimer, John. Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 653.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [653] (796/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2014. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. pp. 192–195. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. p. 219. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [659] (802/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Moorehead, John (1977). In Defiance of The Elements: A Personal View of Qatar. Quartet Books. p. 23. ISBN 9780704321496.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. pp. 666–670.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [667] (810/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 669.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 670.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. pp. 673–4.

- 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. p. 225. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 287. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.