Harty

Harty is a small hamlet on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent consisting of a few cottages, a church and a public house, the Ferry Inn (a Grade II listed building[1]). At the 2011 Census the population of the hamlet was included in the civil parish of Leysdown-on-Sea.

| Harty | |

|---|---|

Harty Church on the bank of the Swale | |

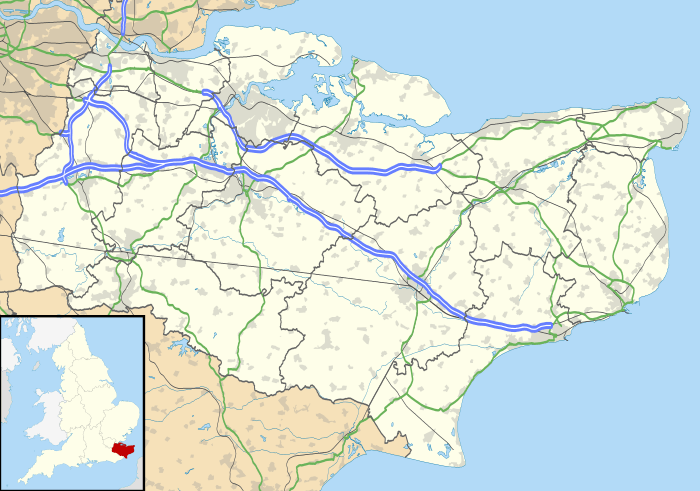

Harty Location within Kent | |

| OS grid reference | TR023663 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Sheerness |

| Postcode district | ME12 4 |

| Police | Kent |

| Fire | Kent |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament |

|

History

The earliest recorded evidence of human occupation comes from a late Bronze Age hoard of axes, gouges bronze founder's appliances and metal. The find has wider importance from the information it gives into methods used for casting in the late Bronze Age.[2] Evidence of Roman occupation also exists; finds of tesserae, roof and flue tiles may indicate the site of a Roman villa.[3]

During the Middle Ages there were extensive salt workings. Remains today consist of groups of salt mounds which are the waste left over from the process.[4] Park Farmhouse is a Grade II listed building[5] dating from the 16 century.

In 1798 Edward Hasted recorded that an earlier form of the name was 'Harteigh' which he presumes came from the Saxon Heord-tu, an island "filled with herds of cattle".[6] Other forms of the name have been Hertei (1086), Heartege (1100), Herteye (1242) and the modern Harty by 1610.[7] Hasted also noted that the islet was part of the hundred of Faversham unlike the rest of the island of Sheppey which came within Milton Hundred.[6] There were also 4000 sheep and six cottages with 20 people, but of those 20 six were on permanent poor relief and another 3 occasionally so.[6]

Harty is a few minutes walk from the Swale National Nature Reserve. Public footpaths run from Harty, along the southern extent of the reserve to the hamlet of Shellness, and back around the reserve's northern perimeter to Harty.

Church of St Thomas the Apostle

The church of 'St Thomas the Apostle' is a Grade II* listed building.[8] The date of founding cannot be fixed with certainty. The official listing dates it to late 11th or early 12th century, based in part on Pevsner (1977) and in part on Patience & Perks. Patience & Perks start by reporting the raid by Harold in 1052 and then note that ""The date ascribed to the church of 1089 would be consistent with a re-building following damage by the Danes".[9] However, on the next page they discuss the narrow walls which are indicative of Saxon builders and note that in 1989, when a shallow trench was excavated in the south wall, traces of Saxon work were found.[10] Tufa stone was rarely used after the early Norman period, and so the use of it in a window in the north wall would indicate a date of no later than the end of the 11th century.[10] Patience & Perks observe that the "date of AD 1089 is ascribed to the Norman work, which may well have been the re-building of an earlier structure desecrated by the Danish invaders".[10]

After 1200 the north aisle was built and the original north wall pierced to form the existing arcade. The now blocked off south door was cut at about this time. In the head of the jamb is a scratch dial or primitive sundial.[10] A little later the chancel was rebuilt, extended to create the sanctuary and the porch to the north door constructed.[11] At what point the Norman chancel arch was removed is unclear, possibly at the time of the rebuilding but certainly prior to the erection of the rood screen. The 14th century saw the construction of the vestry, Lady chapel and buttressing of the south and west walls. The existing rood screen probably dates to this period.[12] There is no rood loft but the stairs leading to one are still visible. The stairs lead out of what is now the vestry but was originally the north chapel. This was a 14th-century extension of the north aisle eastwards. Within the vestry is the remains of an aumbry or secure cupboard for holding books and valuable plate.[13] The 19th and 20th centuries have also left their marks. The former saw heavy restoration including a complete reroofing of the nave (including reraftering) and heavy pointing of the exterior. The later has seen necessary restoration to the west end which was damaged by a bomb during World War II.[14]

To the north of the high altar there is a niche which may have held a figure of St Thomas. Traces of a 14C painting therein have been obscured by a 15C one.[15] There is also a niche for a figure in the Lady chapel, recently (c.1999) filled by a statue of Our Lady of Walsingham.[16] Against the western wall of the lady chapel is a 14th-century oak muniment chest, the front of which is carved with a representation of a joust. In 1987 it was stolen and recovered from Phillips auction rooms. To protect it, the lady chapel arch is filled with an iron screen. It was during the installation of this screen that the shallow trench referred to above was dug.[16]

The church is unusual that there is no electricity or running water. Lighting in the nave is provided by hanging paraffin lamps and by wall mounted lamps with reflectors. The parish is within the Diocese of Canterbury and deanery of Sittingbourne.[6] There is one bell hung for swing chiming of approximately 4 long hundredweight (450 lb; 200 kg).[17]

- Niche beside the high altar

- Paraffin lamp in nave

- Stairs to the old rood loft

- East end showing rood screen

- West end showing hanging lamps and the bell tower base

Ferries and bridge

Hasted also records the existence of the ferry between Oare (in Kent) and the island across The Swale.[6] The old ferry is reflected in the name of the adjacent Inn. The rights to the ferry were, and still are, held by the landlord of the "Ferry House" Inn.[18] The southern, mainland, terminus was close to the villages of Oare and Uplees. Today the remains of the southern jetty are on the coast of the Oare Marshes nature reserve. A small cluster of buildings close by still bear the name Harty Ferry Cottages. During World War I the Royal Engineers built a bridge across the Swale.[7][lower-alpha 1] The last ferry boat fell to pieces around 1941 and has never been replaced.[18] However the official list entry for the church mentions the ferry as being in use until 1946.[8] An attempt to start a small hovercraft service between the Harty Ferry Inn and Oare Creek in 1970 by the then landlord, Ben Fowler, failed after a few days.

Hasted (1798) records:

... that there was formerly a bridge leading from hence [Harty] into Shepey, then called Tremseth bridge, which had been broken down by a violent inundation of the sea, and the channel thereby made so deep, that a new one could not be laid; and therefore the inhabitants of Shepey, who before repaired it, maintained in the room of it two ferry-boats, to carry passengers to and fro. There is now no bridge here, and the fleet which divided this island from that of Shepey is become so very narrow, and has for several years past been so much filled up, that, excepting at high tides and overflow of the waters, Harty has ceased to have any appearance of an island.[6]

The "violent inundation" appears to have occurred in 1293. The silting of the fleet rendering Harty a tidal island was complete by the time Hastead was writing in 1798. A hundred years later (in 1893) during floods the fleet grew to be 100 yards (91 m) wide but today is cut off from Windmill Creek by a causeway.[7]

References

Notes

- Patience & Perks refers to this as a bailey bridge, but the bailey bridge was not developed until 1941. The Swale at this point is 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) wide and so possibly some form of pontoon bridge is meant.

Citations

- Historic England & 1258222.

- Historic England & 463487.

- Historic England & 1316228.

- Historic England & 463505.

- Historic England & 1258074.

- Hasted (1798).

- Patience & Perks p. 3.

- Historic England & 1258076.

- Patience & Perks p. 4.

- Patience & Perks p. 5.

- Patience & Perks pp. 5–6.

- Patience & Perks p. 6.

- Patience & Perks p. 10.

- Patience & Perks p. 12.

- Patience & Perks pp. 6–7.

- Patience & Perks p. 7.

- Love.

- Taylor (2015).

Bibliography

- Hasted, Edward (1798), "Parishes", The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, Institute of Historical Research, 6: 276–283, retrieved 10 October 2015

- Historic England, "Bronze hoard found c1873 (463487)", PastScape, retrieved 10 October 2015

- Historic England, "Three salt mounds near Capel Gate (463505)", PastScape, retrieved 10 October 2015. See also monuments numbers 463496, 463499, 463508, 463511, 463514, 463502, 463520, 463523, 463526, 463529, 463538 and 463517.

- Historic England, "Park Farmhouse (Grade II) (1258074)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 10 October 2015

- Historic England, "Church of St Thomas the Apostle (Grade II*) (1258076)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 10 October 2015

- Historic England, "Ferry House Inn (Grade II) (1258222)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 10 October 2015

- Historic England, "Surface finds of Roman tesserae (1316228)", PastScape, retrieved 10 October 2015

- Love, Dickon, "Full List of Bell Towers", Love's Guide to the Church Bells of Kent, retrieved 20 September 2018

- Patience, Colin; Perks, Hugh (ARICS), St, Thomas the Apostle, Isle of Harty, published by the church

- Pevsner, Nicholas (1977), "North-East and East Kent", Buildings of England

- Taylor, Lisa (2015), "Back in the day", The Ferry House Inn, retrieved 10 October 2015