Mika'el Abiy

Mika’el Abiy is a tabia or municipality in the Dogu’a Tembien district of the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. The tabia centre is in Megesta village, located approx. 7 km to the southeast of the woreda town Hagere Selam.

Mika’el Abiy | |

|---|---|

Mount Gumawta dominates the Mika’el Abiy skyline | |

Mika’el Abiy Location within Ethiopia | |

| Coordinates: 13°37′N 39°12′E | |

| Country | Ethiopia |

| Region | Tigray |

| Zone | Debub Misraqawi (Southeastern) |

| Woreda | Dogu’a Tembien |

| Area | |

| • Total | 33.76 km2 (13.03 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,320 m (7,610 ft) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 5,698 |

| • Density | 169/km2 (440/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

Geography

The tabia stretches down south of the main road towards Rubaksa, which is a wider area with several springs and traditional irrigation. The highest peak is Gumawta (2815 m a.s.l.) on the Tsatsen plateau and the lowest place Rubaksa (1920 m a.s.l.).

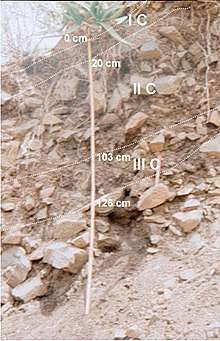

Geology and soils

Geological formations

From the higher to the lower locations, the following geological formations are present:[1]

- Upper basalt

- Interbedded lacustrine deposits

- Lower basalt

- Amba Aradam Formation

- Antalo Limestone

- Quaternary alluvium and freshwater tufa[2]

Soilscape

The main geomorphic units, with corresponding soil types are:[3][4]

- Hagere Selam Highlands, along the basalt and sandstone ridge

- Associated soil types

- Inclusions

- Rock outcrops and very shallow soils (Lithic Leptosol)

- Rock outcrops and very shallow soils on limestone (Calcaric Leptosol)

- Deep dark cracking clays with very good natural fertility, waterlogged during the wet season (Chromic Vertisol, Pellic Vertisol)

- Shallow stony dark loams on calcaric material (Calcaric Regosol, Calcaric Cambisol)

- Brown loamy soils on basalt with good natural fertility (Luvisol)

- Gently rolling Antalo Limestone plateau, holding cliffs and valley bottoms on limestone

- Associated soil types

- Inclusions

- Rock outcrops and very shallow soils (Lithic Leptosol)

- Shallow very stony loamy soil on limestone (Skeletic Calcaric Cambisol)

- Deep dark cracking clays with very good natural fertility, waterlogged during the wet season (Chromic Vertisol, Pellic Vertisol)

- Brown to dark sands and silt loams on alluvium (Vertic Fluvisol, Eutric Fluvisol, Haplic Fluvisol) and colluvium (Calcaric Regosol)

Springs

As there are no permanent rivers, the presence of springs is of utmost importance for the local people. The following are the main springs in the tabia:[5]

- May Zahla in Dingilet

- May Ayni in Rubaksa

Livelihood

The population lives essentially from crop farming, supplemented with off-season work in nearby towns. The land is dominated by farmlands which are clearly demarcated and are cropped every year. Hence the agricultural system is a permanent upland farming system, and the population are not nomads.[6]

Population

The tabia centre Megesta holds a few administrative offices and some small shops. The villages close to Hagere Selam (Dingilet and Harena) have established a new settlement, at the margin of Hagere Selam, where the inhabitants benefit from the proximity of the town.[5] The main other populated places in the tabia are:[7]

|

|

Religion and churches

Most inhabitants are Orthodox Christians. The following churches are located in the tabia:

|

|

Legends and myths

In Megesta, there is a strong story about the Queen of Sheba who was transformed in a snake; the track of the snake is represented by a line of trees up to now. In the northern part of Harena, called Argak'a, there is a large rock of more than 50 m² - the story goes that a certain Ilias transported it up to there.[8]

History

The history of the tabia is strongly confounded with the history of Tembien.

Roads and communication

The main road Mekelle – Hagere Selam – Abiy Addi runs at the north and west of the tabia. Inhabitants mostly move on foot to Hagere Selam from where they can travel further. A rural access road links Hagere Selam to the main villages of Mika’el Abiy.

Schools

Almost all children of the tabia are schooled,[9] though in some schools there is lack of classrooms, directly related to the large intake in primary schools over the last decades.[10] Schools in the tabia include Selam Seret school.

Tourism

Its mountainous nature and proximity to Mekelle makes the tabia fit for tourism.[11]

Touristic attractions

- Dingilet waterfall

- Rubaksa irrigated gardens

- Gumawta peak

Geotouristic sites

The high variability of geological formations and the rugged topography invites for geological and geographic tourism or “geotourism”.[12] Geosites in the tabia include:

|

|

Trekking routes

Trekking routes have been established in this tabia.[13] The tracks are not marked on the ground but can be followed using downloaded .GPX files.[14]

- Route 10, from Haddush Addi, through T’eshi to Rubaksa (8 km, from the highest to the lowest places in the tabia)

- Route 11, from Megesta, through Harena to Hagere Selam (8 km)

- Route 16, from Rubaksa to Togogwa (7 km)

Inda Siwa, the local beer houses

In the main villages, there are traditional beer houses (Inda Siwa), often in unique settings, which are a good place for resting and chatting with the local people. Most renown in the tabia are[5]

- Letesillasie Gebrecherkos in Megesta village

- Amit Gebregziabher in Megesta village

- Tsehaynesh Tesfay in Megesta village

Accommodation and facilities

The facilities are very basic.[15] One may be invited to spend the night in a rural homestead or ask permission to pitch a tent. Hotels are available in Hagere Selam and Mekelle.

More detailed information

For more details on environment, agriculture, rural sociology, hydrology, ecology, culture, etc., see the overall page on the Dogu’a Tembien district.

Gallery

A farmer ploughing at Haddush Addi.

A farmer ploughing at Haddush Addi. View towards Dingilet from Mt Gumawta.

View towards Dingilet from Mt Gumawta. Waterfall in Dingilet.

Waterfall in Dingilet.

References

- Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F. (2019). Regional geology of the Dogu'a Tembien massif. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Moeyersons, J. and colleagues (2006). "Age and backfill/overfill stratigraphy of two tufa dams, Tigray Highlands, Ethiopia: Evidence for Late Pleistocene and Holocene wet conditions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 230 (1–2): 162–178. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.07.013.

- Nyssen, J.; Naudts, J.; De Geyndt, K.; Haile, Mitiku; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Deckers, J. (2008). "Soils and land use in the Tigray highlands (Northern Ethiopia)". Land Degradation and Development. 19 (3): 257–274. doi:10.1002/ldr.840.

- Nyssen, Jan; Tielens, Sander; Gebreyohannes, Tesfamichael; Araya, Tigist; Teka, Kassa; Van De Wauw, Johan; Degeyndt, Karen; Descheemaeker, Katrien; Amare, Kassa; Haile, Mitiku; Zenebe, Amanuel; Munro, Neil; Walraevens, Kristine; Gebrehiwot, Kindeya; Poesen, Jean; Frankl, Amaury; Tsegay, Alemtsehay; Deckers, Jozef (2019). "Understanding spatial patterns of soils for sustainable agriculture in northern Ethiopia's tropical mountains". PLOS One. 14 (10): e0224041. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224041. PMC 6804989. PMID 31639144.

- What do we hear from the farmers in Dogu'a Tembien? [in Tigrinya]. Hagere Selam, Ethiopia. 2016. p. 100.

- Nyssen, J.; Naudts, J.; De Geyndt, K.; Haile, Mitiku; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Deckers, J. (2008). "Soils and land use in the Tigray highlands (Northern Ethiopia)". Land Degradation and Development. 19 (3): 257–274. doi:10.1002/ldr.840.

- Jacob, M. and colleagues (2019). Geo-trekking map of Dogu'a Tembien (1:50,000). In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Seifu Gebreselassie; Lanckriet, S. (2019). Local myths in relation to the natural environment of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-Trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains, the Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Socio-demographic profile, food insecurity and food-aid based response. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. 2019. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Hartjen, C.A. and Priyadarsini, S., 2012. Denial of Education. In The Global Victimization of Children (pp. 271-321). Springer, Boston, MA. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4614-2179-5_8 .

- Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. 2019. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Miruts Hagos and colleagues (2019). Geosites, Geoheritage, Human-Environment Interactions, and Sustainable Geotourism in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-Trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains, the Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_1. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Nyssen, Jan (2019). Description of Trekking Routes in Dogu'a Tembien. GeoGuide. Springer-Nature. pp. 557–675. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_38. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/traces/tag/nyssen-jacob-frankl

- Nyssen, Jan (2019). "Logistics for the Trekker in a Rural Mountain District of Northern Ethiopia". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. Springer-Nature. pp. 537–556. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_37. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.