Hardboiled

Hardboiled (or hard-boiled) fiction is a literary genre that shares some of its characters and settings with crime fiction (especially detective fiction and noir fiction). The genre's typical protagonist is a detective who battles the violence of organized crime that flourished during Prohibition (1920–1933) and its aftermath, while dealing with a legal system that has become as corrupt as the organized crime itself.[1] Rendered cynical by this cycle of violence, the detectives of hardboiled fiction are often antiheroes. Notable hardboiled detectives include Philip Marlowe, Mike Hammer, Sam Spade, Lew Archer, and The Continental Op.

Genre pioneers

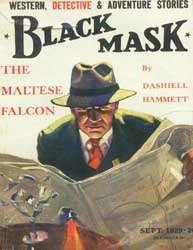

The style was pioneered by Carroll John Daly in the mid-1920s,[2] popularized by Dashiell Hammett over the course of the decade, and refined by James M. Cain and by Raymond Chandler beginning in the late 1930s.[3] Its heyday was in 1930s–50s America.[4]

Pulp fiction

From its earliest days, hardboiled fiction was published in and closely associated with so-called pulp magazines. Pulp historian Robert Sampson argues that Gordon Young's "Don Everhard" stories (which appeared in Adventure magazine from 1917 onwards), about an "extremely tough, unsentimental, and lethal" gun-toting urban gambler, anticipated the hardboiled detective stories.[5] In its earliest uses in the late 1920s, "hardboiled" did not refer to a type of crime fiction; it meant the tough (cynical) attitude towards emotions triggered by violence.

The hardboiled crime story became a staple of several pulp magazines in the 1930s; most famously Black Mask under the editorship of Joseph T. Shaw,[3][6] but also in other pulps such as Dime Detective and Detective Fiction Weekly.[7][8] Consequently, "pulp fiction" is often used as a synonym for hardboiled crime fiction or gangster fiction;[9] some would distinguish within it the private-eye story from the crime novel itself.[10] In the United States, the original hardboiled style has been emulated by innumerable writers, including James Ellroy, Paul Cain, Sue Grafton, Chester Himes, Paul Levine, John D. MacDonald, Ross Macdonald, Walter Mosley, Sara Paretsky, Robert B. Parker, and Mickey Spillane. Later, many hardboiled novels were published by houses specializing in paperback originals, most notably Gold Medal, and in later decades republished by houses such as Black Lizard.

Photo by Paolo Monti, 1975

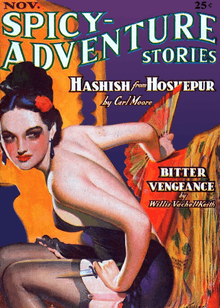

Photo by Paolo Monti, 1975 Femmes fatales were standard fare in hardboiled fiction.

Femmes fatales were standard fare in hardboiled fiction.

Relation to noir fiction

Hardboiled writing is also associated with "noir fiction". Eddie Duggan discusses the similarities and differences between the two related forms in his 1999 article on pulp writer Cornell Woolrich.[11] In his full-length study of David Goodis, Jay Gertzman notes: "The best definition of hard boiled I know is that of critic Eddie Duggan. In noir, the primary focus is interior: psychic imbalance leading to self-hatred, aggression, sociopathy, or a compulsion to control those with whom one shares experiences. By contrast, hard boiled 'paints a backdrop of institutionalized social corruption'".[12]

References

- Porter, Dennis (2003). "Chapter 6: The Private Eye". In Priestman, Martin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-521-00871-6.

- Ousby, I (1995). "Black Mask". The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English. p. 89.

- Collins, Max Allan (1994). "The Hard-Boiled Detective". In de Andrea, William L (ed.). Encyclopedia Mysteriosa. MacMillan. pp. 153–4. ISBN 978-0-02-861678-0.

- Abbott, Megan (2002). The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir. pp. 2–3..

- Sampson, Robert & Deandrea, William L. (Editor) (1994). "Pulps". Encyclopedia Mysteriosa. MacMillan. pp. 287–9. ISBN 978-0-02-861678-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) "Extremely tough, unsentimental and lethal, Everhard foreshadowed the hard-boiled characters of the following decade".

- Budrys, Algis (October 1965). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 142–150.

- Sampson, Robert & Deandrea, William L. (Editor) (1994). "Pulps". Encyclopedia Mysteriosa. MacMillan. pp. 287–9. ISBN 978-0-02-861678-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Mystery Time Line: Hard-Boiled Mysteries". MysteryNet. Archived from the original on 2006-10-21. A brief survey of the genre's early days, focusing on Black Mask.

- Hoggart, Richard (1957). The Uses of Literacy. p. 258.

- Abbott, Megan. "Toward a Hardboiled Genealogy" (PDF). pp. 10–11. Hardboiled/noir "family tree", by crime fiction author and scholar Megan Abbott.

- Duggan, Eddie (1999). "Writing in the darkness: The world of Cornell Woolrich". CrimeTime. 2 (6): 113–126.

- Gertzman, J. A. (2018). Pulp According to David Goodis. Lutz, FL: Down & Out Books. p. 53.

Further reading

- Breu, Christopher (July 2004). "Going blood-simple in poisonville: hard-boiled masculinity in Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest". Men and Masculinities. 7 (1): 52–76. doi:10.1177/1097184X03257449.

- Duggan, Eddie (2000). "Dashiell Hammett: Detective, Writer". Crimetime. 3 (2): 101–114 – via Academia.edu.

- Gosselin, Adrienne Johnson (2002). Multicultural Detective Fiction: Murder from the "Other" Side. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-3153-3.

- Haut, Woody (1996). Pulp Culture: Hardboiled Fiction and the Cold War. Serpent's Tail. ISBN 1-85242-319-6.

- Horsley, Lee. "1920–1945: The Interwar Period and the Development of Hard-boiled Crime Fiction". crimeculture.com.

- Horsley, Lee. "American Hard-Boiled Crime Fiction, 1920s–1940s". crimeculture.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-18. Retrieved 2006-09-16. An essay on the form's early history.

- Horsley, Lee. "Hard-boiled Investigators". crimeculture.com.

- Irwin, John T. (2006). Unless the Threat of Death Is Behind Them: Hard-Boiled Fiction and Film Noir. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8435-7.

- Kemp, Simon (2006). Defective Inspectors: Crime-fiction Pastiche in Late Twentieth-century. Maney Publishing. ISBN 1-904350-51-8.

- Lovisi, Gary (March 1995). "The Hard-Boiled Way". A Shot in the Dark.

- Marling, Professor William (Case Western Reserve University). "Detective Novels: An Overview". detnovel.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-18. Retrieved 2007-10-06. History of the genre.

- Mizejewski, Linda (2004). Hardboiled and High Heeled: The Woman Detective in Popular Culture. Routledge Chapman Hall. ISBN 0-415-96970-0.

- O'Brien, Geoffrey (2005-08-27). "The Hardboiled Era: A Checklist, 1929–1958". miskatonic.org/rara-avis. A chronology of significant hardboiled novels, compiled by critic Geoffrey O'Brien for the 1981 edition of his Hardboiled America.

- O'Brien, Geoffrey (1997). Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir. Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80773-4.

- Panek, LeRoy Lad (2000). New Hard-Boiled Writers: 1970s–1990s. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-87972-819-1.

- Server, Lee (2002). Encyclopedia of Pulp Fiction Writers. Facts On File Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4577-1.

External links

- "A–Z List: Hard-boiled Guide". rraymond.narold.ru. A list of hard-boiled and noir writers.

- "Hard-boiled Detective". rraymond.narold.ru. Comprehensive bibliographies.

- "Hardboiled Bibliographies". miskatonic.org/rara-avis. 2005-08-28. Comprehensive bibliographies of many important hardboiled/noir authors.

- "Twists, Slugs and Roscoes: A Glossary of Hardboiled Slang". miskatonic.org. 2016-05-26.