Hannes Bok

Hannes Bok, pseudonym for Wayne Francis Woodard (UK: /ˈwʊdɑːrd/ (![]()

Wayne Woodard | |

|---|---|

Hannes Bok | |

| Born | Wayne Francis Woodard July 2, 1914 Kansas City, Missouri, United States |

| Died | April 11, 1964 (aged 49) New York City, New York, United States |

| Pen name | Hannes Bok |

| Occupation | Illustrator, writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1939–1957 (SF magazine artist)[1] |

| Genre | Fantasy |

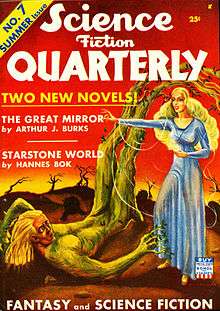

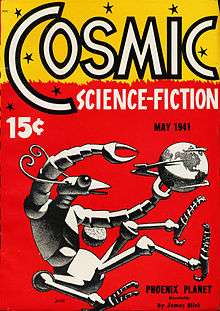

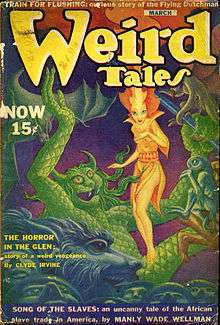

Today, Bok is best known for his cover art which appeared on various pulp and science fiction magazines, such as Weird Tales, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, Other Worlds, Super Science Stories, Imagination, Fantasy Fiction, Planet Stories, If, Castle of Frankenstein and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Life and career

Wayne Woodard (the name is sometimes mistakenly rendered as "Woodward") was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His parents divorced when he was five; and his father and stepmother, strict disciplinarians, discouraged his artistic efforts. Once he graduated high school, in Duluth, Minnesota, Bok cut off contact with his father and moved to Seattle to live with his mother. There he became active in SF fandom, including the publication and illustration of fanzines. It was in connection with these activities that he originated his pseudonym, first "Hans", then "Hannes", Bok. The pseudonym derives from Johann Sebastian Bach (whose name can be rendered both as "Johann S. Bach" and "Johannes Bach").

In 1937, Bok moved to Los Angeles, where he met Ray Bradbury. In 1938, he relocated to Seattle – where he worked for the W.P.A. and became acquainted with artists like Mark Tobey and Morris Graves. Late in 1939, Bok moved to New York City in order to be closer to the editors and magazines which would publish his work, and where he became a member of the influential Futurians science fiction fans.[4] Bok had corresponded with and had met Maxfield Parrish (ca. 1939?), and the influence of Parrish's art on Bok's is evident in his choice of subject matter, use of color, and application of glazes. Bok was also homosexual, according to friends Forrest J Ackerman and Emil Petaja; the erotic fantasy elements of his artwork, especially his male nude subjects, display homoerotic overtones unusual for the time.

Like his contemporary Virgil Finlay, Hannes Bok broke into commercial art and achieved initial career success as a Weird Tales artist – though he did so through one of the stranger events in the history of science fiction and fantasy. In the summer of 1939, Ray Bradbury carried samples of Bok's art eastward to introduce his friend's work to magazine editors at the first World Science Fiction Convention.[4] This was a bold move, since Bradbury was a neophyte with no connections to commercial art or the magazine industry; but it reflects the close ties within the fan and professional community. Bradbury was, at the time, a 19-year-old newspaper seller, and he borrowed funds for the trip from fellow science fiction fan Forrest J Ackerman. Bradbury succeeded; Farnsworth Wright, editor of Weird Tales, accepted Bok's art, which debuted in the December 1939 issue of Weird Tales. More than 50 issues of the magazine featured Bok's pen-and-ink work until March 1954. Bok also executed six color covers for Weird Tales between March 1940 and March 1942. Weird Tales also published five of Bok's stories and two of his poems between 1942 and 1951. Once he broke through into professional publications, Bok moved to New York City and lived there the rest of his life.

Throughout his life, Bok was deeply interested in astrology, as well as in the music of the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, with whom Bok had a correspondence. (Bok's copy of Karl Ekman's Jean Sibelius: His Life and Personality [Knopf, 1938], for example, is annotated with Bok's comments and astrological charts.) As the years passed, Bok became prone to disagreements with editors over money and artistic issues; he grew reclusive and mystical, and preoccupied with the occult. He eked out a living, often in near poverty, until his death in 1964. He died, apparently of a heart attack (he "starved to death" according to Ackerman), at the age of 49.[5] ISFDB catalogs only a few 1956 interior illustrations after March 1954, his last for Weird Tales, and only two cover illustrations after January 1957.[1]

Bok as an author

As an author, Bok is best known for his novels The Sorcerer's Ship, originally published in the December 1942 issue of John W. Campell's fantasy magazine Unknown; and The Blue Flamingo/Beyond the Golden Stair. The Blue Flamingo first appeared in the January 1948 issue of Startling Stories. Bok later performed an extensive revision and expansion of this work, published posthumously as Beyond the Golden Stair (1970). Both novels have been re-issued in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. Bok also was allowed to complete two novellas left unfinished by A. Merritt at the time of his death in 1943. These were published as The Blue Pagoda (1946) and The Black Wheel (1947). (Bok's commitment to fantasy and science fiction had occurred in 1927 in connection with Merritt's The Moon Pool in Amazing Stories – one of those conversion experiences common among young SF fans.) Also published posthumously was a collection of Bok's poetry, Spinner of Silver and Thistle (1972).

Bok as an artist

Bok is better known for his art than for his fiction. His style could alternate between, or combine, lush romanticism and humorous grotesquery. His use of time-consuming glazing techniques for his paintings impeded his productivity and limited his output, and therefore his commercial success. He also spent time carving figures in wood and making masks in papier mache. In the 1950s he was able to do more book-jacket illustrations, which he found less irksome than magazine work; though he could never have abandoned the latter. His striking wraparound cover for the November 1963 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, illustrating Roger Zelazny's "A Rose for Ecclesiastes", was published in the last months of his life.

Bok and Ed Emshwiller shared one of the inaugural Hugo Awards for science fiction achievement in 1953, as the previous year's best "Cover Artist" (a tie); Virgil Finlay was recognized as the best "Interior Illustrator". Cover and interior illustration were not thereafter distinguished by the Hugo Award for Best Artist under various names.[3]

Bok and Emil Petaja

The science fiction and fantasy author Emil Petaja (1915–2000) was lifelong friend of Bok and collector of his work. After Bok's death, Petaja did as much as anyone to keep the artist's work before the public eye.

Bok and Petaja first met in the summer of 1936. According to Petaja, Bok and his friend Harold Taves were hitch-hiking from Seattle to New York City when they stopped off in Montana, USA, to see the aspiring writer. At first correspondents, Bok and Petaja soon became close friends. The two had much in common – including an interest in fantasy fiction, the Kalevala (the Finnish verse epic), and the music of Sibelius.

Petaja's first book, Brief Candle (1936), contained twelve poems by Petaja and twelve illustrations by Bok. Petaja printed this now rare chapbook by running-off copies on the mimeograph machines at Bozeman Campus, Montana State University, where he was a student in creative writing. According to Petaja, approximately 40 to 50 copies were printed with many "given to friends and well wishers."

Bok and Petaja's friendship continued in Los Angeles, where each had relocated in 1937. Throughout 1937 and 1938, Petaja and Bok shared an apartment, and together they attended fan meetings, haunted second-hand book and magazine shops, went to the movies, and helped each other with their poems and stories. They also immersed themselves in the primordial Los Angeles science fiction scene. Bok and Petaja befriended Ray Bradbury – then still a teenager – as well as Forrest J. Ackerman, Henry Kuttner and others.

In And Flights of Angels, Petaja recounts: "Perhaps when all is washed down over the dam, my major claim to fame will rest in the fact that it was I who got Hannes down to Los Angeles and I who dragged him, reluctantly, to the meetings of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society. Where we met Ray Bradbury. . . . It was at Clifton's Cafeteria on Broadway. We couldn't afford to eat there, usually, but we took advantage of the free lime sherbet. In that fabled back room where so many of the s-f elite have sat around the long table chewing the fat, fanwize, Hannes first met Forrie Ackerman, Henry Kuttner, et al. But it was Ray Bradbury who took to Hannes instanter and proved to be such a rare and wonderful friend to him a little later on."

"Besides introducing Hannes to Ray Bradbury, I take pride in the fact that this brief Los Angeles period of Bok's life was one of the most productive of his life. He produced a dozen color paintings based on Peer Gynt, as samples to show book publishers what he could do. He painted "The Mermaid" and several Enchanted City themes. He wrote scads of poetry. All of which does indicate that, for all his beefs, he was happy then. He might lash out cruelly about this or that, but nobody I have known had as great a capacity for enjoying and sensating all there was around him."

In 1967, three years after Bok's death, Petaja founded the Bokanalia Memorial Foundation. The foundation was set up "with the help and encouragement of Harold Taves of Seattle and Ray Bradbury of Los Angeles and the Golden Gate Futurians of San Francisco . . . . The avowed intention of Bokanalia is simply to keep the great imaginative art of Hannes Bok from slipping into oblivion, and to make new (better than pulp) prints available to his many admirers all over the world".

Between 1967 and 1970, Petaja published five portfolios of Bok's art. Those portfolios include Variations on Bok Theme, (black & white portfolio, 1967); The Famous Power Series, (black & white portfolio, with text by Bok, 1969); and A Memorial Portfolio, (color portfolio, with booklet with text by Petaja, 1970). Petaja also authored a commemorative volume, And Flights of Angels: The Life and Legend of Hannes Bok (Bokanalia Memorial Foundation, 1968). Along with brief contributions from Roger Zelazny, Jack Gaughan, Donald Wollheim and others, And Flights of Angels contains Petaja's long biographical essay on the artist, a checklist of Bok's published artwork and writings, and reproductions of a substantial number of the artist's drawings, prints and illustrations. Later, under the SISU imprint (and on behalf of the Bokanalia Foundation), Petaja published an illustrated volume of Bok's poetry, Spinner of Silver and Thistle (1972), as well as editing The Hannes Bok Memorial Showcase of Fantasy Art (1974).

Much of the Bok material included in the portfolios and books published and authored by Petaja came from Petaja's personal collection. Petaja owned at least a dozen paintings, as well as dozens of sketches, drawings, prints and three-dimensional objects. Among Petaja's most beloved possessions was the first sketch Bok ever drew for him, a piece from 1936 called "Gleef," which hung on the wall of Petaja's San Francisco home. Petaja also collected examples of Bok's published work – such as magazine covers, interior illustrations, dust jackets, book covers, and more. Additionally, Petaja amassed Bok manuscripts (both published and unpublished fiction and poetry), as well as letters, books, other printed matter and unique, one-of-a-kind objects.

See also

References

- Hannes Bok at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved 2013-04-11. Select a title to see its linked publication history and general information. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image or linked contents.

- Jones, D., et al., eds., Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary, 17th ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 563.

- "Bok, Hannes" Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine. The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index of Art Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- "Hannes Bok: Futurian Artist in Chief". Frederik Pohl. The Way the Future Blogs. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- "Hannes Bok, Part 2: The story with the unhappy ending". Frederik Pohl. The Way the Future Blogs. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hannes Bok. |

- Works by Hannes Bok at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Hannes Bok at Internet Archive

- Cuyler W. Brooks Jr.'s "Hannes Bok Illustration Index"

- Hannes Bok at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Spacelight: Hannes Bok

- Hannes Bok gallery at American Art Archives