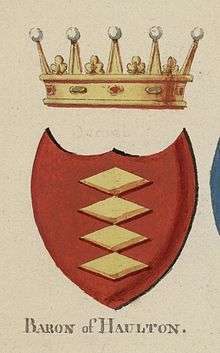

Halton (barony)

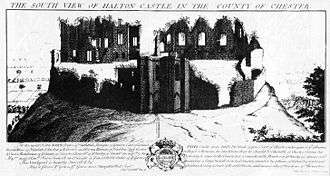

The Barony of Halton, in Cheshire, England, comprised a succession of 15 barons who held under the overlordship of the County Palatine of Chester ruled by the Earl of Chester. It was not therefore an English feudal barony which was under full royal jurisdiction, which is the usual sense of the term,[lower-alpha 1] but a separate class of barony within a palatinate. After the Norman conquest, William the Conqueror created three earldoms to protect his border with Wales, namely Shrewsbury, Hereford and Chester. Hugh Lupus was appointed Earl of Chester and he appointed his cousin, Nigel of Cotentin, as the first Baron of Halton.[2] Halton was a village in Cheshire which is now part of the town of Runcorn. At its centre is a rocky prominence on which was built Halton Castle, the seat of the Barons of Halton; the castle is now a ruin.

The Barons

In order, with the dates they held the title, the Barons of Halton were as follows.

1 Nigel of Cotentin

- (c. 1071–1080)

He was also the hereditary Constable of Chester. In 1077 he fought against the Welsh at the Battle of Rhuddlan.[3] It is almost certain that he built a motte-and-bailey castle on Halton Hill the remains are still visible today.[4]

2 William FitzNigel

- (1080–1134)

The son of Nigel de Cotentin. He also held the honour of being the Marshal of the Earls' host, which was an important position in the Norman military hierarchy. In addition to his land in Halton, his estate included land in other parts of Cheshire and also in Normandy.[5] He married the eldest daughter of Yorfid, the baron of Widnes. Yorfid left no male heir and on his death the Lancashire manors of Widnes, Appleton, Cronton and Rainhill came to William.[2] In 1115 he established a priory of the Augustinian Order of Canons Regular in Runcorn.[6] He was buried at Chester.[7]

3 William fitz William

- (1134–1150)

The son of William fitz Nigel. In 1134 he moved the priory from Runcorn to a site to the east of Halton. This became Norton Priory.[8] William died childless in Normandy.[9]

4 Eustace fitz John

- (1150–1157)

He obtained the title by marriage, his second wife being the sister of William FitzWilliam. He had inherited the barony of Knaresborough and by his first marriage had also gained the baronies of Malton and Alnwick.[9] He was killed fighting the Welsh.[6]

5 Richard fitz Eustace

- (1157–1171)

The son of Eustace fitz John. He married into the de Lacy family of Pontefract.[10]

6 John fitz Richard

- (1171–1190)

The son of Richard fitz Eustace. He was a governor in Ireland for Henry II. Being a patron of science, he maintained an astronomer at Halton Castle. He founded a Cistercian monastery at Stanlow.[9] In 1190 he granted the second known charter for a ferry at Runcorn Gap. He served with Richard I in the Third Crusade and died at the siege of Acre.[11]

7 Roger de Lacy

- (1190–1211)

The son of John fitz Richard. He adopted the surname of de Lacy. He was a renowned soldier and was nicknamed "Hell" Lacy for his military daring. In 1192 he was also serving with Richard I in the Third Crusade. Later he served King John in the unsuccessful attempt to thwart the French conquest of Normandy following which he was made High Sheriff of Lancashire. He was buried in the abbey founded by his father at Stanlow.[11][12]

8 John de Lacy

- (1211–1240)

The son of Roger. He opposed King John and was one of the barons entrusted with the duty of ensuring that the king kept the agreements made in Magna Carta. By marriage he gained more titles, including that of the Earldom of Lincoln. He also gained the manor and the castle of Bolingbroke. He was also buried at Stanlow.[13]

9 Edmund de Lacy

- (1240–1258)

Son of John, and of whom little is known, except that he was also buried at Stanlow.[14]

10 Henry de Lacy

- (1258–1311)

Son of Edmund. He was educated at court and became Chief Councillor to Edward I. While the king was engaged on military conflicts with the Scots, Henry was appointed Protector of the Realm.[13] He transferred the monastery from Stanlow to Whalley.[11] He died at his London home, Lincoln's Inn and was buried in the old St Paul's cathedral.[13]

11 Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

(1311–1322)

Thomas gained the barony of Halton though his marriage to Alice, Henry's daughter. He took up arms against Edward II in 1322. However this rebellion was unsuccessful. He was defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge and then imprisoned in his own castle at Pontefract. A few days later he was beheaded outside the city. Later a cult of martyrdom developed around him.[11]

12 Sir William Glinton (?)

- (1322–1351)

There is some uncertainty about the 12th baron. It has been suggested that it was Sir William Glinton. He was a distinguished knight who may have held the honour as a non-hereditary arrangement or he may have held it during the life of Alice, widow of Thomas of Lancaster.[13] Another suggestion is that the 12th baron was Thomas' brother, Henry Wryneck.[15]

13 Henry Grosmont

- (1351–1361)

Henry gained the barony of Halton as nephew of Thomas of Lancaster. He was appointed as the 1st Duke of Lancaster, one of the first Knights of the Order of the Garter.[16] He served the king in France and died of the plague.[13] He was buried at Leicester.[17]

14 John of Gaunt

- (1361–1399)

John of Gaunt gained the barony by his marriage to Blanche, daughter and heiress of the 13th baron. He was appointed regent during the infancy of Richard II.[13] He was also buried in St Paul's cathedral.[17]

15 Henry Bolingbroke

- (1399–1413)

Henry Bolingbroke was the eldest son of John of Gaunt. He was banished from England by Richard II and at the time of his father's death he was in exile in France. When he returned to England to claim his estates the people rallied round him. Richard II was deposed and Henry was crowned King Henry IV. Henry procured an Act of Parliament to ordain that the Duchy of Lancaster would remain in the personal possession of the reigning monarch and the barony of Halton is now vested in that dukedom.[18]

References and notes

Notes

- This source does not list the barony of Halton as a feudal barony but refers to the "Lord of Halton, hereditary constable of the County Palatine" (i.e. of Chester).[1]

Citations

- Sanders (1960), p. 138

- Starkey (1990), p. 8

- Whimperley (1986), pp. 8–9

- McNeil (1987), p. 1

- Whimperley (1986), p. 9

- Nickson (1887), p. 136

- Whimperley (1981), p. 1

- Starkey (1990), p. 9

- Starkey (1990), p. 30

- Whimperley (1986), p. 10

- Nickson (1887), p. 144

- Kingsford, C. L. (rev Paul Dalton) (2004), "Lacy, Roger de (d. 1211)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 3 July 2013 ((subscription or UK public library membership required))

- Starkey (1990), p. 31

- Whimperley (1986), p. 11

- Whimperley (1986), p. 13

- Nickson (1887), p. 146

- Whimperley (1986), p. 2

- Nickson (1887), pp. 146–147

Sources

- McNeil, Robina (ed.) (1987), Halton Castle: A Visual Treasure, Liverpool: North West Archaeological Trust, ISBN 978-0-9510204-1-8CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nickson, Charles (1887), History of Runcorn, London and Warrington: Mackie & Co., OCLC 5389146CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanders, I. J. (1960), English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086–1327, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 4814461271CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Starkey, H. F. (1990), Old Runcorn, Halton: Halton Borough CouncilCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whimperley, Arthur (1981), Halton Castle: An Introduction & Visitors' Handbook, Widnes: Arthur WhimperleyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whimperley, Arthur (1986), The Barons of Halton, Widnes: MailBook PublishingCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)