Toupée

A toupée (/tuːˈpeɪ/ too-PAY) is a hairpiece or partial wig of natural or synthetic hair worn to cover partial baldness or for theatrical purposes. While toupées and hairpieces are typically associated with male wearers, some women also use hairpieces to lengthen existing hair, or cover a partially exposed scalp. The desire to wear hairpieces is caused in part by a long-standing bias against balding that crosses cultures, dating to at least 3100 BC. Toupée manufacturers' financial results indicate that toupée use is in overall decline, due in part to alternative methods for dealing with baldness, and to greater cultural acceptance of the condition.

Toupées and wigs

While most toupées are small and designed to cover bald spots at the top and back of the head, large toupées are not unknown.

Toupées are often referred to as hairpieces, units, or hair systems. Many women now wear hairpieces rather than full wigs if their hair loss is confined to the top and crown of their heads.

Etymology

According to various sources referenced by Dictionary.com,[1] toupée is related to the French words "top," or "tuft;" tuft as the curl or lock of hair at the top of the head, not necessarily relating to covering baldness. Toupée is related to the diminutive toupe more recently (as of the 17th century).[2][3]

History

While wigs have a very long and somewhat traceable history, the origin of the "toupée" is more difficult to define, but one can reasonably infer that the first toupée was a piece of hair, worn on the head, with the intention of deceiving the viewer into believing the hair was natural, rather than a wig worn for decorative or ceremonial purposes.

Use and attitudes in ancient history

The desire for men to wear hairpieces is a response to a long-standing cultural bias against balding men that crosses cultures. Between 1 BC and AD 1, the Roman poet Ovid wrote Ars Amatoria ("The Art of Love") in which he expressed "Ugly are hornless bulls, a field without grass is an eyesore, So is a tree without leaves, so is a head without hair."[5] Another example of this bias, in a later and different culture, can be found in The Arabian Nights (c. AD 800-900), in which the female character Scheherazade asks "Is there anything more ugly in the world than a man beardless and bald as an artichoke?"[6]

The earliest known example of a toupée was found in a tomb[7] near the ancient Predynastic capital of Egypt, Hierakonpolis. The tomb and its contents date to ca. 3200 – 3100 BC.

At least two ancient Greek statues of men wearing toupées survive today, one identified as a Capitoline type, presently located in Thorvaldsens Museum in Copenhagen.[8]

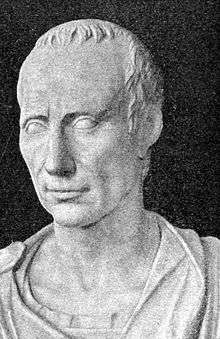

Julius Caesar is known to have worn a toupée. In dismay at his pattern baldness, he tried both wearing a toupée, and shaving his head.[9] Some state that he wore his trademark ceremonial wreath to disguise his shrinking hairline.[4] Roman men of the era were also known to paint their bald heads to appear to have locks of hair.[4]

19th century

In the United States, toupée use (as opposed to wigs) grew in the 19th century. One researcher has noted that this is in part due to a shift in perceptions over the perceived value of aging that occurred at that time. Men chose to attempt to appear younger, and toupées were one method used.

...since 1800, the U.S. Census generally shows far more 39-year-olds than 40-year-olds. Furthermore, the costume of men switched from a design clearly intended to make the young look older to one that was clearly intended to make the old look younger. For example, this era saw the decline of the wig and the rise of the toupée.[10]

20th century

By the 1950s, it was estimated that over 350,000 U.S. men wore hairpieces, out of a potential 15 million wearers. Toupée manufacturers helped to build credibility for their product starting in 1954, when several makers advertised hairpieces in major magazines and newspapers, with successful results. Key to the promotion and acceptance of toupées was improved toupée craftsmanship, pioneered by Max Factor. Factor's toupées were carefully made and almost invisible, with each strand of hair sewed to a piece of fine flesh-colored lace, and in a variety of long and short hairstyles. Factor, also a Hollywood makeup innovator, was the supplier of choice for most Hollywood actors.[11]

By 1959, total U.S. sales were estimated by Time magazine to be $15 million a year. Sears-Roebuck, which had sold toupées as early as 1900 via its mail order catalog, tried to tap into the market by sending out 30,000 special catalogs by direct mail to a targeted list, advertising "career winning" hair products manufactured by Joseph Fleischer & Co., a respected wig manufacturer.[12] Toupées continued to be advertised in print, likely with heavier media buys taking place in magazines with the appropriate male demographic. A typical "advertorial" can be found in Modern Mechanix.

By 1970, Time magazine estimated that in the U.S., toupées were worn by more than 2.5 million men out of 17–20 million balding men. The increase was chalked up once again to further improvements in hairpiece technology, a desire to seem more youthful, and the long hairstyles that were increasingly in fashion.[13]

21st century

Toupée and wig manufacture is no longer centered in the U.S., but in Asia.[14] Aderans, based in Japan, is one of the world’s largest wigmakers, with 35% share of the Japanese domestic market.

From 2002 to 2004, new orders from Aderans's male customers (both domestic and international) slipped by 30%. Researchers at both the Daiwa Institute and Nomura Research – two key Japanese economic research institutes – conclude that there is "no sign of a recovery" for the toupée industry.[14] Sales for male wearers have continued to fall at Aderans in every year since, aside from 2016 where they increased slightly.[15]

These numbers confirm the media consensus[14] that toupée use is in decline overall. No reliable sources have stated numbers for the estimated population of toupée users in the U.S. or internationally, so comparisons to past eras are difficult to make with any accuracy. Regardless, hairpiece manufacturers and retailers continue to market their goods in print, on television, and on the internet.

Manufacture

Toupées are often custom made to the needs of the wearer, and can be manufactured using either synthetic or human hair. Toupées are usually held to one's head using an adhesive, but the cheaper versions often merely use an elastic band.

Toupée manufacture is often done at the local level by a craftsman, but large wig manufacturers also produce toupées. Both individuals and large firms have constantly innovated to produce better quality toupées and toupée material, with over 60 patents for toupées.[16] and over 260 for hairpieces [17] filed at the U.S. Patent Office since 1790.

The first patent for a toupée was filed in 1921, and the first patent for a "hairpiece" was filed in 1956.[17]

Hair weaves

Hair weaves are a technique in which the toupée's base is then woven into whatever natural hair the wearer retains. While this may result in a less detectable toupée, the wearer can experience discomfort, and sometimes hair loss from frequently retightening of the weave as one's own hair grows. After about six months a person can begin to lose hair permanently along the weave area, resulting in traction alopecia. Hair weaves were very popular in the 1980s & 1990s, but are not usually recommended because of the potential for permanent hair damage and hair loss.

Use and maintenance

While toupée dealers attempt to match the toupée's color to the natural hair color of the wearer, sometimes the colors are not identical. This color mismatch is often exacerbated when a toupée is poorly cared for and fades, or the wearer's hair color turns gray while the toupée retains its original color. However a good salon will take this into account and will have the expertise to handle any problems. New technology has allowed hair manufacturers to mimic human hair, overcoming many of the weaknesses of human hair.

While toupée dealers and manufacturers usually advertise their products showing men swimming, water-skiing and enjoying watersports, these activities can often cause irreversible wear to the toupée. Saltwater and chlorine can cause a toupée to "wear out" quickly. Many shampoos and soaps will damage toupée fibers, which unlike natural hair, cannot grow back or replace themselves.

While dealers of toupées can in fact help many customers to care for their toupées and make their presence virtually undetectable, the hairpieces must be of very high quality to begin with, carefully fitted, and maintained regularly and carefully. Even the best-cared-for toupée will need to be replaced on a regular basis, due to wear and, over time, to the growing areas of baldness on the wearer's head and changes in the shade of remaining hair. Some recommend that if one chooses to use a toupée, three should be owned at any one time - one to wear while its counterpart is being cleaned, and a spare.[18]

Alternatives

Men typically wear toupées after resorting to less extreme methods of coverage. The first tactic is to make remaining hair appear thick and widespread through a combover. Other alternatives include non-surgical hair replacement, which consists of a very thin hairpiece which is put on with a medical adhesive and worn for weeks at a time.[19]

Medications and medical procedures

Propecia, Rogaine and other pharmaceutical remedies were approved for treatment of Alopecia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the 1990s. These have proven capable of regrowing or sustaining existing hair at least part of the time.

However, hair transplantation, which guarantees at least some immediate results, has often replaced the use of toupées among those who can afford them, particularly onscreen celebrities.

Baldness as fashion, acceptance of hair loss

Other trends leading to the decline in toupée use include a rise in acceptance of baldness by those men afflicted with it. Short haircuts, in fashion since the 1990s, have tended to minimize the appearance of baldness, and many balding men choose to shave their heads entirely.

Chemotherapy and injury

An important exception to the typical reasons for wearing a toupée is that recovering chemotherapy patients sometimes wear toupées. This type of hairpiece is technically referred to as a hair prosthesis. A positive self-image has often been said to assist in the recovery process, and doctors often help direct recovering patients to find hairpieces to help project their usual healthy appearance. This effort is particularly made when the recovering patient is a child, or a woman.

Another exception is that if a person's head has been damaged by an accident, or through a surgical procedure, the victim or patient may wish to conceal scarring. Steven Van Zandt of the E Street Band wore a toupée in his role on The Sopranos to cover scarring he had received after a car accident several years prior. While performing onstage, and in his personal life, Van Zandt favors a bandanna.

There are at least four charities that specialize in providing hairpieces for children who have lost hair due to Chemotherapy, medical treatment or head injury:

- Locks of Love - A charitable organization for children who have lost their hair after medical treatment

- Wigs for Kids - A charitable organization for children who have lost hair due to chemotherapy

- The American Cancer Society Tender Loving Care Wigs

- Hair That Cares, Inc. - A charitable organization for adults and children who have lost their hair after medical treatment and Alopecia

Humor

Toupées have a long and often humorous history in Western culture. The toupée is a regular butt of jokes in many media, with a typical toupée joke focusing on the wearer's inability to recognize how ineffective the toupée is in concealing his baldness. An early instance of "toupée humor" was an illustration by George Cruikshank in "The Comic Almanack" in 1837, in which he drew the effect of a strong wind, with a man's toupée whipped from his head.[20]

In the 20th century, toupées were a source of humor in virtually all forms of media, including cartoons, films, radio and television. In the 21st century, toupées continue to be a source for humor, with a variety of internet sites devoted to toupées, with a special emphasis on suspected celebrity hairpiece wearers.

Thaddeus Stevens, famed 19th century U.S. Congressman and abolitionist, was known for his humor and wit. On one occasion while in the Capitol, a woman requested a lock of his hair (collecting locks of hair was common at this time). Since he was bald and wearing a toupée, he ripped it off and gave it to her.[21]

Known wearers

Film and television stars of both past and present often wear toupées for professional reasons, particularly as they begin to age and need to maintain the image their fans have become accustomed to. However, many of these same celebrities go "uncovered" when not working or making public appearances.

- Bud Abbott (wore a front toupée in early films)[22]

- Marv Albert

- Neil Aspinall

- Fred Astaire (he appeared sans toupée while entertaining the troops overseas)

- Raymond Bailey

- Edgar Bergen[23]

- Humphrey Bogart[24]

- George Burns[25]

- Julius Caesar[4]

- Archie Campbell - this Hee Haw comedian was said to be so sensitive about his balding head that he would not let visitors see him in the hospital because he could not put on his toupée.

- Sean Connery - Bond actor, used toupée only in movies

- Gary Cooper[26][27] (he was not totally bald but used a "thickening" toupée in later years, which was on display at the Max Factor Museum in Hollywood)

- Howard Cosell[28]

- Bing Crosby (chose not to wear a toupée during WWII USO Tours) [29][30]

- Peter Cushing often wore a toupée in films in later years, but equally often appeared without it, letting the character he was playing dictate the hair style.

- Bobby Darin[31]

- Charles O. Finley, former owner of the Oakland Athletics

- Bruce Forsyth[32]

- Paul Harvey[33]

- Ted Healy (Original owner of the Three Stooges)

- Charlton Heston

- Frankie Howerd (toupée later for sale at auction) [34]

- Gene Kelly (when not on camera, he wore caps or trilby hats)

- Jack Klugman - he wore one during his time on The Odd Couple and Quincy, M.E., but his appearances on Match Game during the same time, he did not wear one.

- Frankie Laine

- Bela Lugosi (he was not bald, but in Dracula he wore a front toupée to give him a widow's peak)

- Fred MacMurray[35]

- Miles Malleson

- Groucho Marx - he wore one for his television quiz show You Bet Your Life, but during the same period would sometimes appear on talk shows without it.

- John L. Mica - US Congressman from Florida [36]

- Ray Milland

- Ricardo Montalbán

- James C. Morton

- Charles Nelson Reilly - it was a long-standing joke on Match Game in the 1970s. During the airing of one broadcast, he actually took off his toupée and loaned it to a bald guest.

- Carl Reiner - the comic actor would regularly appear with or without the toupée, depending on the requirements of the role.

- Rob Reiner - Reiner started wearing a hairpiece during the second season of All in the Family to hide his premature hair loss, as he was playing a character who was in his early 20s.

- Burt Reynolds

- John D. Rockefeller[37]

- William Roth - Senator from Delaware[38][39]

- William Shatner[40]

- Frank Sinatra[41]

- James Stewart[30]

- Rip Taylor[42]

- James Traficant[43]

- Billy Vaughn[44]

- John Wayne[41][45]

- Hank Williams

References

- "the definition of toupee". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "toupee." Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. 13 Aug. 2007. <Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/toupee>.

- "toupee." Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 13 Aug. 2007. <Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/toupee>.

- Luciano, Lynne (9 January 2002). Looking Good: Male Body Image in Modern America. Macmillan. ISBN 9780809066384. Retrieved 13 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- "The Love Books of Ovid Index". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Book Review of Looking Good, author?, New York Times, date? (registration required)

- The Ancient Near East, Amelie Kuhrt, Routledge, September 1995, ISBN ?

- Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Styles, Sheila Dillon, Cambridge University Press, 2006 ISBN ?

- "Change and Permanence in Men's Clothes", A. Hyatt Mayor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 8, No. 9 (May, 1950), pp. 262-269 doi:10.2307/3257422

- TEXT ANALYSIS FOR THE SOCIAL SCIENCES; Edited by CARL W. ROBERTS; Iowa State University; LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS, 1997 Mahwah, New Jersey, page 19 https://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=88053789

- "Glamour For Sale". Time. August 23, 1954

- "Proper Toppers". Time. March 30, 1959

- "Rugs and Plugs". Time. June 10, 1970.

- "The Times & The Sunday Times". Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Aderan Sales Figures". Aderans Co Ltd. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Patent Database Search Results: toupee in US Patent Collection". patft.uspto.gov. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Patent Database Search Results: hairpiece in US Patent Collection". patft.uspto.gov. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Why the Toupee Went Out of Fashion". baldinglife.com. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "How Hair Replacement Systems Work - Infographic". 8 January 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Cruikshank, Thackeray and the Victorian Eclipse of Satire". Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Trefousse, Hans L. Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian (1997)

- http://www.movietome.com/people/114383/bud-abbott/trivia.html%5B%5D

- Reed, Leonard (January 9, 1951). "For Men Only: The Male's Crowning Glory". Portland Press Herald. Portland, Maine. p. 5. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Nathan, George Jean (1953). The Theatre in the Fifties. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- "George Burns Took His Cigars, Music With Him". Orlando Sentinel. March 22, 1996. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Thorpe, Vanessa (9 February 2008). "Clandestine mistress of Bogart dies". The Observer. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Herman, Valli. "Frederick's of Hollywood and other hot spots". The Free Lance–Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. p. 11. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Shapiro, Leonard (April 24, 1995). "Howard Cosell Dies at 77". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- "Bing to Bataan". Time. Feb. 9, 1942

- Rivenburg, Roy (February 2, 1997). "Under The Rug: Toupees Continue To Be A Conversation Piece". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Hajdu, David (February 2005). "Chameleon With a Toupee". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- "Don't mention the toupee". The Daily Telegraph. 28 June 1997. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- "Good days for Paul Harvey". Chicago Tribune. August 4, 2002. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Copping, By Jasper. "Frankie Howerd's toupee for sale". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- "My Three Sons". Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Groer, Anne (May 19, 1993). "Capitol Domes -- Taking A Strand On Baldness In Image-Conscious Washington". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Warner Books. (1998).

- "New Rumor in the White House: Clinton's Bald Truth". Los Angeles Times. February 23, 1997. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Segrave, Kelly (1996). Baldness: A Social History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 125.

- Robin Curtis tells a tale on Nimoy, Lloyd & Shatner's Toupee on YouTube

- Century, Douglas (December 24, 2000). "A Little Sympathy for the Toupee . . . er, Hair System". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-19. Retrieved 2014-10-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "On Jim Traficant's Hair, and Character". Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Lowe, Herman (November 19, 1987). "Billy Vaughn began the Hilltoppers at the old Boots and Saddle". The Daily News. Bowling Green. p. 6–A. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- "John Wayne's wig up for auction". BBC News. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 2012-01-26.