Hammered dulcimer

The hammered dulcimer (also called the hammer dulcimer, dulcimer, or tympanon) is a percussion-stringed instrument which consists of strings typically stretched over a trapezoidal resonant sound board. The hammered dulcimer is set before the musician, who in more traditional styles may sit cross-legged on the floor, or in a more modern style may stand or sit at a wooden support with legs. The player holds a small spoon-shaped mallet hammer in each hand to strike the strings (see Appalachian dulcimer). The Graeco-Roman dulcimer ("sweet song") derives from the Latin dulcis (sweet) and the Greek melos (song). The dulcimer, in which the strings are beaten with small hammers, originated from the psaltery, in which the strings are plucked.[1]

a musician playing a Diatonic Hammered Dulcimer | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cimbalom Dulcimer Four-hammer dulcimer Hammer dulcimer de: Hackbrett it: Salterio es: Dulcémele pl: Cymbały fa: Santoor, Santur uk: Tsymbaly fr: Tympanon zh: Yangqin ko: Yanggeum kh: ឃឹម Khim vi: Tam Thập Lục th: ขิม Khim tt: чимбал çimbal |

| Classification | Percussion instrument (Chordophone), String instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 314.122-4 (Simple chordophone sounded by hammers) |

| Developed | Antiquity |

| Related instruments | |

| Alpine Zither, Appalachian Dulcimer, Autoharp, Board Zither, Concert Zither, Psaltery | |

Hammered dulcimers and other similar instruments are traditionally played in Iraq, India, Iran, Southwest Asia, China, Korea, and parts of Southeast Asia, Central Europe (Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, Slovakia, Poland, Czech Republic, Switzerland (particularly Appenzell), Austria and Bavaria), the Balkans, Eastern Europe (Ukraine and Belarus), and Scandinavia. The instrument is also played in the United Kingdom (Wales, East Anglia, Northumbria), and the US, where its traditional use in folk music saw a notable revival in the late 20th century.[2]

Strings and tuning

.jpg)

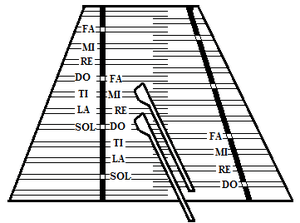

A dulcimer usually has two bridges, a bass bridge near the right and a treble bridge on the left side. The bass bridge holds up bass strings, which are played to the left of the bridge. The treble strings can be played on either side of the treble bridge. In the usual construction, playing them on the left side gives a note a fifth higher than playing them on the right of the bridge.

The dulcimer comes in various sizes, identified by the number of strings that cross each of the bridges. A 15/14, for example, has 15 strings crossing the treble bridge and 14 crossing the bass bridge, and can span three octaves. The strings of a hammered dulcimer are usually found in pairs, two strings for each note (though some instruments have three or four strings per note). Each set of strings is tuned in unison and is called a course. As with a piano, the purpose of using multiple strings per course is to make the instrument louder, although as the courses are rarely in perfect unison, a chorus effect usually results like a mandolin. A hammered dulcimer, like an autoharp, harp, or piano, requires a tuning wrench for tuning, since the dulcimer's strings are wound around tuning pins with square heads. (Ordinarily, 5 mm "zither pins" are used, similar to, but smaller in diameter than piano tuning pins, which come in various sizes ranging upwards from "1/0" or 7 mm.)

The strings of the hammered dulcimer are often tuned according to a circle of fifths pattern.[3][4] Typically, the lowest note (often a G or D) is struck at the lower right-hand of the instrument, just to the left of the right-hand (bass) bridge. As a player strikes the courses above in sequence, they ascend following a repeating sequence of two whole steps and a half step. With this tuning, a diatonic scale is broken into two tetrachords, or groups of four notes. For example, on an instrument with D as the lowest note, the D major scale is played starting in the lower-right corner and ascending the bass bridge: D – E – F♯ – G. This is the lower tetrachord of the D major scale. At this point the player returns to the bottom of the instrument and shifts to the treble strings to the right of the treble bridge to play the higher tetrachord: A – B – C♯ – D. The player can continue up the scale on the right side of the treble bridge with E – F♯ – G – A – B, but the next note will be C, not C♯, so he or she must switch to the left side of the treble bridge (and closer to the player) to continue the D major scale. See the drawing on the left above, in which "DO" would correspond to D (see Movable do solfège).

The shift from the bass bridge to the treble bridge is required because the bass bridge's fourth string G is the start of the lower tetrachord of the G scale. The player could go on up a couple notes (G - A - B), but the next note will be a flatted seventh (C natural in this case), because this note is drawn from the G tetrachord. This D major scale with a flatted seventh is the mixolydian mode in D.

The same thing happens as the player goes up the treble bridge – after getting to La (B in this case), one has to go to the left of the treble bridge. Moving from the left side of the bass bridge to the right side of the treble bridge is analogous to moving from the right side of the treble bridge to the left side of the treble bridge.

The whole pattern can be shifted up by three courses, so that instead of a D-major scale one would have a G-major scale, and so on. This transposes one equally tempered scale to another. Shifting down three courses transposes the D-major scale to A-major, but of course the first Do-Re-Mi would be shifted off the instrument.

This tuning results in most, but not all, notes of the chromatic scale being available. To fill in the gaps, many modern dulcimer builders include extra short bridges at the top and bottom of the soundboard, where extra strings are tuned to some or all of the missing pitches. Such instruments are often called "chromatic dulcimers" as opposed to the more traditional "diatonic dulcimers".

The tetrachord markers found on the bridges of most hammered dulcimers in the English-speaking world were introduced by the American player and maker Sam Rizzetta in the 1960s.[5]

In the Alps there are also chromatic dulcimers with crossed strings, which are in a whole tone distance in every row. This chromatic Salzburger hackbrett was developed in the mid 1930s from the diatonic hammered dulcimer by Tobi Reizer and his son along with Franz Peyer and Heinrich Bandzauner. In the postwar period it was one of the instruments taught in state-sponsored music schools.[6]

Hammered dulcimers of non-European descent may have other tuning patterns, and builders of European-style dulcimers sometimes experiment with alternate tuning patterns.

Hammers

The instrument is referred to as "hammered" in reference to the small mallets (referred to as hammers) that players use to strike the strings. Hammers are usually made of wood (most likely hardwoods such as maple, cherry, padauk, oak, walnut, or any other hardwood), but can also be made from any material, including metal and plastic. In the Western hemisphere, hammers are usually stiff, but in Asia, flexible hammers are often used. The head of the hammer can be left bare for a sharp attack sound, or can be covered with adhesive tape, leather, or fabric for a softer sound. Two-sided hammers are also available. The heads of two sided hammers are usually oval or round. Most of the time, one side is left as bare wood while the other side may be covered in leather or a softer material such as piano felt.

Several traditional players have used hammers that differ substantially from those in common use today. Paul Van Arsdale (1920-2018), a player from upstate New York, used flexible hammers made from hacksaw blades, with leather-covered wooden blocks attached to the ends (these were modeled after the hammers used by his grandfather, Jesse Martin). The Irish player John Rea (1915–1983) used hammers made of thick steel wire, which he made himself from old bicycle spokes wrapped with wool. Billy Bennington (1900–1986), a player from Norfolk, England, used cane hammers bound with wool.

Variants and adaptations

The hammered dulcimer was extensively used during the Middle Ages in England, France, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain. Although it had a distinctive name in each country, it was everywhere regarded as a kind of psalterium. The importance of the method of setting the strings in vibration by means of hammers, and its bearing on the acoustics of the instrument, were recognized only when the invention of the pianoforte had become a matter of history. It was then perceived that the psalterium (in which the strings were plucked) and the dulcimer (in which they were struck), when provided with keyboards would give rise to two distinct families of instruments, differing essentially in tone quality, in technique and in capabilities. The evolution of the psalterium resulted in the harpsichord; that of the dulcimer produced the pianoforte.[7]

Around the world

Versions of the hammered dulcimer are used throughout the world. In Eastern Europe, a larger descendant of the hammered dulcimer called the cimbalom is played and has been used by a number of classical composers, including Zoltán Kodály, Igor Stravinsky, and Pierre Boulez. The khim is the name used by the Thai, the Khmer, and the Laotians for the hammered dulcimer.[8]

See also

- List of hammered dulcimer players

- Santoor – India

- Santur – Iran and Iraq and Azerbaijan

- Yangqin – China

References

- "Definition of DULCIMER". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Groce, Nancy, The Hammered Dulcimer in America. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1983. Page 72-73.

- Rizzetta, Sam. "Hammer Dulcimer: History and Playing". Encyclopedia Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Traditional or Fifth-Interval Tuning". Dusty Strings. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- Rizzetta, Sam. "Luthier Spotlight Sam Rizzetta and Music, Dulcimer Sessions". Encyclopedia Smithsonian. Mel Bay. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Gifford, Paul M., The Hammered Dulcimer: A History, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2001. Page 81.

- Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Terry E. Miller, "Khim [Khimm]", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

Further reading

- Gifford, Paul M. (2001), The Hammered Dulcimer: A History, The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-3943-1. A comprehensive history of the hammered dulcimer and its variants.

- Kettlewell, David (1976), The Dulcimer, PhD thesis. History and playing traditions around the world; web-version at https://web.archive.org/web/20110717071302/http://www.new-renaissance.net/dulcimer.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hammered dulcimers. |

- Santur on Nay-Nava, the encyclopedia of Persian music instruments

- Pete Rushefsky, "Jewish Strings: An Introduction to the Klezmer Tsimbl" (Related to the Hammered Dulcimer) (archive from 27 December 2009).

- Smithsonian Institution booklet on hammered dulcimer history and playing

- Smithsonian Institution booklet on making a hammered dulcimer (by Sam Rizzetta)

- The dulcimer from the Hans Adler Collection and Museum, Wits University, RSA

- Hammered dulcimers from polish collections (Polish folk musical instruments)

- East Anglian Dulcimers(ongoing historic research by John & Katie Howson about dulcimer players and makers from Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire and Essex, UK.)