Gulf War syndrome

Gulf War syndrome or Gulf War illness is a chronic and multi-symptomatic disorder affecting returning military veterans of the 1990–1991 Persian Gulf War.[4][5][6] A wide range of acute and chronic symptoms have been linked to it, including fatigue, muscle pain, cognitive problems, insomnia,[3] rashes and diarrhea.[7] Approximately 250,000[8] of the 697,000 U.S. veterans who served in the 1991 Gulf War are afflicted with enduring chronic multi-symptom illness, a condition with serious consequences.[9]

| Gulf War Illness | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gulf War illnesses, and chronic multisymptom illness[1][2] |

| |

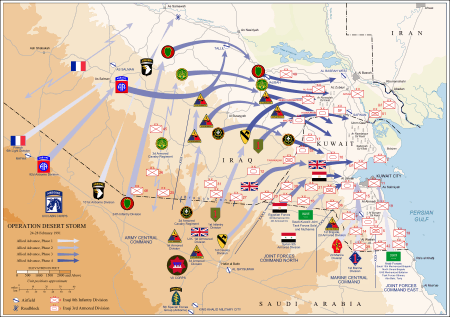

| Summary of the Operation Desert Storm offensive ground campaign, February 24–28, 1991, by nationality | |

| Symptoms | Vary somewhat among individuals and include fatigue, headaches, cognitive dysfunction, musculoskeletal pain, insomnia,[3] and respiratory, gastrointestinal, and dermatologic complaints |

| Causes | Toxic exposures during the 1990–91 Gulf War |

| Differential diagnosis | Chronic fatigue syndrome / myalgic encephalitis (CFS/ME); fibromyalgia; multiple sclerosis (MS) |

| Frequency | 25% to 34% of the 697,000 U.S. troops of the 1990–91 Gulf War |

From 1995 to 2005, the health of combat veterans worsened in comparison with nondeployed veterans, with the onset of more new chronic diseases, functional impairment, repeated clinic visits and hospitalizations, chronic fatigue syndrome-like illness, posttraumatic stress disorder, and greater persistence of adverse health incidents.[10]

Exposure to pesticides and pills containing pyridostigmine bromide (used as a pretreatment to protect against nerve agent effects) has been found to be associated with the neurological effects seen in Gulf war syndrome.[11][12] Other causes that have been investigated are sarin, cyclosarin, and emissions from oil well fire, but their relationship to the illness is not as clear.[11][12]

Studies have consistently indicated that Gulf War syndrome is not the result of combat or other stressors and that Gulf War veterans have lower rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than veterans of other wars.[9][11]

According to a 2013 report by the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, veterans of the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan may also suffer from Gulf War syndrome,[13] though later findings identified causes that would not have been present in those wars.[11][12]

Signs and symptoms

According to an April 2010 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) sponsored study conducted by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), part of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, 250,000[8] of the 696,842 U.S. servicemen and women in the 1991 Gulf War continue to suffer from chronic multi-symptom illness, which the IOM now refers to as Gulf War illness. The IOM found that it continued to affect these veterans nearly 20 years after the war.

According to the IOM, "It is clear that a significant portion of the soldiers deployed to the Gulf War have experienced troubling constellations of symptoms that are difficult to categorize," said committee chair Stephen L. Hauser, professor and chair, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). "Unfortunately, symptoms that cannot be easily quantified are sometimes incorrectly dismissed as insignificant and receive inadequate attention and funding by the medical and scientific establishment. Veterans who continue to suffer from these symptoms deserve the very best that modern science and medicine can offer to speed the development of effective treatments, cures, and—we hope—prevention. Our report suggests a path forward to accomplish this goal, and we believe that through a concerted national effort and rigorous scientific input, answers can be found."[8]

Questions still exist regarding why certain veterans showed, and still show, medically unexplained symptoms while others did not, why symptoms are diverse in some and specific in others, and why combat exposure is not consistently linked to having or not having symptoms. The lack of data on veterans' pre-deployment and immediate post-deployment health status and lack of measurement and monitoring of the various substances to which veterans may have been exposed make it difficult — and in many cases impossible — to reconstruct what happened to service members during their deployments nearly 20 years after the fact, the committee noted.[8] The report called for a substantial commitment to improving identification and treatment of multisymptom illness in Gulf War veterans focussing on continued monitoring of Gulf War veterans, improved medical care, examination of genetic differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups and studies of environment-gene interactions.[8]

A variety of signs and symptoms have been associated with GWI:

| Symptom | U.S. | UK | Australia | Denmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 23% | 23% | 10% | 16% |

| Headache | 17% | 18% | 7% | 13% |

| Memory problems | 32% | 28% | 12% | 23% |

| Muscle/joint pain | 18% | 17% | 5% | 2% (<2%) |

| Diarrhea | 16% | 9% | 13% | |

| Dyspepsia/indigestion | 12% | 5% | 9% | |

| Neurological problems | 16% | 8% | 12% | |

| Terminal tumors | 33% | 9% | 11% |

- * This table applies only to coalition forces involved in combat.

| Condition | U.S. | UK | Canada | Australia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin conditions | 20–21% | 21% | 4–7% | 4% |

| Arthritis/joint problems | 6–11% | 10% | (-1)–3% | 2% |

| Gastro-intestinal (GI) problems | 15% | 5–7% | 1% | |

| Respiratory problem | 4–7% | 2% | 2–5% | 1% |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 1–4% | 3% | 0% | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2–6% | 9% | 6% | 3% |

| Chronic multi-symptom illness | 13–25% | 26% |

Birth defects have been suggested as a consequence of Gulf War deployment. However, a 2006 review of several studies of international coalition veterans' children found no strong or consistent evidence of an increase in birth defects, finding a modest increase in birth defects that was within the range of the general population, in addition to being unable to exclude recall bias as an explanation for the results.[15] A 2008 report stated that "it is difficult to draw firm conclusions related to birth defects and pregnancy outcomes in Gulf War veterans", observing that while there have been "significant, but modest, excess rates of birth defects in children of Gulf War veterans", the "overall rates are still within the normal range found in the general population".[16] The same report called for more research on the issue.

Comorbid illnesses

Gulf War veterans have been identified to have an increased risk of multiple sclerosis.[17]

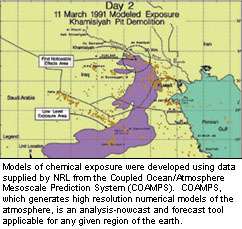

A 2017 study by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs found that veterans possibly exposed to chemical warfare agents at Khamisiyah experienced different patterns of brain cancer mortality risk compared to the other groups, with veterans possibly exposed having a higher risk of brain cancer in the time period immediately following the Gulf War.[18]

Causes

The United States Congress mandated the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs' contract with the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to provide reports on Gulf War illnesses. Since 1998, the NAS's Institute of Medicine (IOM) has authored ten such reports.[19] In addition to the many physical and psychological issues involving any war zone deployment, Gulf War veterans were exposed to a unique mix of hazards not previously experienced during wartime. These included pyridostigmine bromide pills (given to protect troops from the effects of nerve agents), depleted uranium munitions, and multiple simultaneous vaccinations including anthrax and botulinum toxin vaccines. The oil and smoke that spewed for months from hundreds of burning oil wells presented another exposure hazard not previously encountered in a war zone. Military personnel also had to cope with swarms of insects, requiring the widespread use of pesticides. High-powered microwaves were used to disrupt Iraqi communications, and though it is unknown whether this might have contributed to the syndrome, research has suggested that safety limits for electromagnetic radiation are too lenient.[20]

The Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses (RAC), a VA federal advisory committee mandated by Congress in legislation enacted in 1998,[21][22] found that pre-2005 studies suggested the veterans' illnesses are neurological and apparently are linked to exposure to neurotoxins, such as the nerve gas sarin, the anti-nerve gas drug pyridostigmine bromide, and pesticides that affect the nervous system. The RAC concluded in 2004 that, "research studies conducted since the war have consistently indicated that psychiatric illness, combat experience or other deployment-related stressors do not explain Gulf War veterans illnesses in the large majority of ill veterans."[23]

The RAC concluded[11] that "exposure to pesticides and/or to PB [pyridostigmine bromide nerve agent protective pills] are causally associated with GWI and the neurological dysfunction in GW veterans. Exposure to sarin and cyclosarin and to oil well fire emissions are also associated with neurologically based health effects, though their contribution to development of the disorder known as GWI is less clear. Gene-environment interactions are likely to have contributed to development of GWI in deployed veterans. The health consequences of chemical exposures in the GW and other conflicts have been called “toxic wounds” by veterans. This type of injury requires further study and concentrated treatment research efforts that may also benefit other occupational groups with similar exposure-related illnesses."[12]

Earlier considered potential causes

Depleted uranium

Depleted uranium (DU) was widely used in tank kinetic energy penetrator and autocannon rounds for the first time ever during the Gulf War[24] and has been suggested as a possible cause of Gulf War syndrome.[25] A 2008 review by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs found no association between DU exposure and multisymptom illness, concluding that "exposure to DU munitions is not likely a primary cause of Gulf War illness". However, there are suggestions that long-term exposure to high doses of DU may cause other health problems unrelated to GWI.[9]

More recent medical literature reviews disagree, stating for example that, "the number of Gulf War veterans who developed the Gulf War syndrome following exposure to high quantities of DU has risen to about one-third of the 800,000 U.S. forces deployed," with 25,000 of those having suffered premature death.[26] Since 2011, US combat veterans may claim disability compensation for health problems related to exposure to depleted uranium.[27] The Veterans Administration decides these claims on a case-by-case basis.

Pyridostigmine bromide nerve gas antidote

The US military issued pyridostigmine bromide (PB) pills to protect against exposure to nerve gas agents such as sarin and soman. PB was used as a prophylactic against nerve agents; it is not a vaccine. Taken before exposure to nerve agents, PB was thought to increase the efficiency of nerve agent antidotes. PB had been used since 1955 for patients suffering from myasthenia gravis with doses up to 1,500 mg a day, far in excess of the 90 mg given to soldiers, and was considered safe by the FDA at either level for indefinite use and its use to pre-treat nerve agent exposure had recently been approved.[28]

Given both the large body of epidemiological data on myasthenia gravis patients and follow-up studies done on veterans it was concluded that while it was unlikely that health effects reported today by Gulf War veterans are the result of exposure solely to PB, use of PB was causally associated with illness.[9] However, a later review by the Institute of Medicine concluded that the evidence was not strong enough to establish a causal relationship.[29]

Organophosphates

Organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy (OPIDN, aka organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy) may contribute to the unexplained illnesses of the Gulf War veterans.[30][31]

Organophosphate pesticides

The use of organophosphate pesticides and insect repellents during the first Gulf War is credited with keeping rates of pest-borne diseases low. Pesticide use is one of only two exposures consistently identified by Gulf War epidemiologic studies to be significantly associated with Gulf War illness.[32] Multisymptom illness profiles similar to Gulf War illness have been associated with low-level pesticide exposures in other human populations. In addition, Gulf War studies have identified dose-response effects, indicating that greater pesticide use is more strongly associated with Gulf War illness than more limited use.[33] Pesticide use during the Gulf War has also been associated with neurocognitive deficits and neuroendocrine alterations in Gulf War veterans in clinical studies conducted following the end of the war. The 2008 report concluded that "all available sources of evidence combine to support a consistent and compelling case that pesticide use during the Gulf War is causally associated with Gulf War illness."[9]

Sarin nerve agent

Many of the symptoms of Gulf War illness are similar to the symptoms of organophosphate, mustard gas, and nerve gas poisoning.[34][35] Gulf War veterans were exposed to a number of sources of these compounds, including nerve gas and pesticides.[36]

Chemical detection units from Czechoslovakia, France, and Britain confirmed chemical agents. French detection units detected chemical agents. Both Czech and French forces reported detections immediately to U.S. forces. U.S. forces detected, confirmed, and reported chemical agents; and U.S. soldiers were awarded medals for detecting chemical agents. The Riegle Report said that chemical alarms went off 18,000 times during the Gulf War. After the air war started on January 16, 1991, coalition forces were chronically exposed to low but nonlethal levels of chemical and biological agents released primarily by direct Iraqi attack via missiles, rockets, artillery, or aircraft munitions and by fallout from allied bombings of Iraqi chemical warfare munitions facilities.[37]

In 1997, the US Government released an unclassified report that stated:

- "The US Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iraq did not use chemical weapons during the Gulf war. However, based on a comprehensive review of intelligence information and relevant information made available by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), we conclude that chemical warfare (CW) agent was released as a result of US postwar demolition of rockets with chemical warheads in a bunker (called Bunker 73 by Iraq) and a pit in an area known as Khamisiyah."[38]

Over 125,000 U.S. troops and 9,000 U.K. troops were exposed to nerve gas and mustard gas when the Iraqi depot in Khamisiyah was destroyed.

Recent studies have confirmed earlier suspicions that exposure to sarin, in combination with other contaminants such as pesticides and PB were related to reports of veteran illness. Estimates range from 100,000 to 300,000 individuals exposed to nerve agents.[39]

While low-level exposure to nerve agents has been suggested as the cause of GWI, the 2008 report by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War illnesses (RAC) stated that "evidence is inconsistent or limited in important ways."[40] The VA's 2014 RAC report concluded that, "exposure to the nerve gas agents sarin/cyclosarin has been linked in two more studies to changes in structural magnetic resonance imaging findings that are associated with cognitive decrements, further supporting the conclusion from evidence reviewed in the 2008 report that exposure to these agents is etiologically important to the central nervous system dysfunction that occurs in some subsets of Gulf War veterans."[11]

Less likely causes

According to the VA's 2008 RAC report, "For several Gulf War exposures, an association with Gulf War illness cannot be ruled out. These include low-level exposure to nerve agents, close proximity to oil well fires, receipt of multiple vaccines, and effects of combinations of Gulf War exposures." However, several potential causes of GWI were deemed, "not likely to have caused Gulf War illness for the majority of ill veterans," including "depleted uranium, anthrax vaccine, fuels, solvents, sand and particulates, infectious diseases, and chemical agent resistant coating (CARC)," for which "there is little evidence supporting an association with Gulf War illness or a major role is unlikely based on what is known about exposure patterns during the Gulf War and more recent deployments."[40]

The VA's 2014 RAC report reinforced its 2008 report findings: "The research reviewed in this report supports and reinforces the conclusion in the 2008 RACGWVI report that exposures to pesticides and pyridostigmine bromide are causally associated with Gulf War illness. Evidence also continues to demonstrate that Gulf War illness is not the result of psychological stressors during the war." It also found additional evidence since the 2008 report for the role of sarin in GWI, but inadequate evidence regarding exposures to oil well fires, vaccines, and depleted uranium to make new conclusions about them.[11]

Oil well fires

During the war, many oil wells were set on fire in Kuwait by the retreating Iraqi army, and the smoke from those fires was inhaled by large numbers of soldiers, many of whom suffered acute pulmonary and other chronic effects, including asthma and bronchitis. However, firefighters who were assigned to the oil well fires and encountered the smoke, but who did not take part in combat, have not had GWI symptoms.[14](pp148,154,156) The 2008 RAC report states that "evidence [linking oil well fires to GWI] is inconsistent or limited in important ways."[40]

Anthrax vaccine

Iraq had loaded anthrax, botulinum toxin, and aflatoxin into missiles and artillery shells in preparing for the Gulf War and these munitions were deployed to four locations in Iraq.[41] During Operation Desert Storm, 41% of U.S. combat soldiers and 75% of UK combat soldiers were vaccinated against anthrax.[14](p73) Reactions included local skin irritation, some lasting for weeks or months.[42] While the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the vaccine, it never went through large-scale clinical trials.[43]

While recent studies have demonstrated the vaccine is highly reactogenic,[44] and causes motor neuron death in mice,[45] there is no clear evidence or epidemiological studies on Gulf War veterans linking the vaccine to Gulf War illness. Combining this with the lack of symptoms from current deployments of individuals who have received the vaccine led the Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses to conclude that the vaccine is not a likely cause of Gulf War illness for most ill veterans.[9] However, the committee report does point out that veterans who received a larger number of various vaccines in advance of deployment have shown higher rates of persistent symptoms since the war.[46][9]

Combat stress

Research studies conducted since the war have consistently indicated that psychiatric illness, combat experience or other deployment-related stressors do not explain Gulf War veterans illnesses in the large majority of ill veterans, according to a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) review committee.

An April 2010 Institute of Medicine review found, "the excess of unexplained medical symptoms reported by deployed [1991] Gulf war veterans cannot be reliably ascribed to any known psychiatric disorder",[47] although they also concluded that "the constellation of unexplained symptoms associated with the Gulf War illness complex could result from interplay between both biological and psychological factors."[48]

Pathobiology

Chronic inflammation

The 2008 VA report on Gulf War illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans suggested a possible link between GWI and chronic, nonspecific inflammation of the central nervous system that cause pain, fatigue and memory issues, possibly due to pathologically persistent increases in cytokines and suggested further research be conducted on this issue.[49]

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of Gulf War illness has been complicated by multiple case definitions. In 2014, the National Academy of Sciences Institute of Medicine (IOM)—contracted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for the task—released a report concluding that the creation of a new case definition for chronic multisymptom illness in Gulf War veterans was not possible because of insufficient evidence in published studies regarding its onset, duration, severity, frequency of symptoms, exclusionary criteria, and laboratory findings. Instead, the report recommended the use of two case definitions, the "Kansas" definition and the "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)" definition, noting: "There is a set of symptoms (fatigue, pain, neurocognitive) that are reported in all the studies that have been reviewed. The CDC definition captures those three symptoms; the Kansas definition also captures them, but it also includes the symptoms reported most frequently by Gulf War veterans."[50]

The Kansas case definition is more specific and may be more applicable for research settings, while the CDC case definition is more broad and may be more applicable for clinical settings.[50]

Classification

Medical ailments associated with service in the 1990–1991 Gulf War have been recognized by both the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.[4]

Before 1998, the terms Gulf War syndrome, Gulf War veterans' illness, unexplained illness, and undiagnosed illness were used interchangeably to describe chronic unexplained symptoms in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War. The term chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) was first used following publication of a 1998 study[33] describing chronic unexplained symptoms in Air Force veterans of the 1991 Gulf War.[29]

In a 2014 report contracted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Academy of Sciences Institute of Medicine recommended the use the term Gulf War illness rather than chronic multisymptom illness.[50] Since that time, relevant publications by the National Academy of Science and the U.S. Department of Defense have used only the term Gulf War illness (GWI).

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) confusingly still uses an array of both old and new terminology for Gulf War illness. VA's specialty clinical evaluation War Related Illness and Injury Study Centers (WRIISCs) use the recommended term Gulf War illness,[51] as do VA's Office of Research and Development (VA-ORD) and many recent VA research publications.[52] However, VA's Public Health website still uses Gulf War veterans' medically unexplained illnesses, medically unexplained illnesses, chronic multi-symptom illness (CMI), and undiagnosed illnesses, but explains that VA doesn't use the term Gulf War syndrome because of varying symptoms.[53]

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) originally classified individuals with related ailments believed to be connected to their service in the Persian Gulf a special non-ICD-9 code DX111, as well as ICD-9 code V65.5.[54]

Kansas definition

In 1998, the State of Kansas Persian Gulf Veterans Health Initiative sponsored an epidemiological survey led by Dr. Lea Steele of deployment-related symptoms in 2,030 Gulf War veterans. The result was a "clinically based descriptive definition using correlated symptoms" in six symptom groups: fatigue and sleep problems, pain, neurologic and mood, gastrointestinal, respiratory symptoms, and skin (dermatologic) symptoms.[50]

To meet the "Kansas" case definition, a veteran of the 1990–91 Gulf War must have symptoms in at least three of the six symptom domains, which during the survey were scored based on severity ("severity"). Symptom onset must have developed during or after deploying to the 1990–91 Gulf War theatre of operations ("onset") and must have been present in the year before interview ("duration"). Participants were excluded if they had a diagnosis of or were being treated for any of several conditions that might otherwise explain their symptoms ("exclusionary criteria"), including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, chronic infectious disease, lupus, multiple sclerosis, stroke, or any serious psychiatric condition.[50]

Applying the Kansas case definition to the original Kansas study cohort resulted in a prevalence of Gulf War illness of 34.2% in Gulf War veterans and 8.3% in nondeployed Gulf War era veterans, or an excess rate of GWI of 26.3% in Gulf War veterans.[50]

CDC definition

Also in 1998, a study published by Dr. Keiji Fukuda under the auspices of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examined chronic multisymptom illness through a cross-sectional survey of 3,675 ill and healthy U.S. Air Force veterans of the 1990–91 Gulf War, including from a Pennsylvania-based Air National Guard unit and three comparison Air Force units. The CDC case definition was derived from clinical data and statistical analyses.[50]

The result was a symptom-category approach to a case definition, with three symptom categories: fatigue, mood–cognition, and musculoskeletal. To meet the case definition, the veteran of the 1990–91 Gulf War must have symptoms in two of the three categories and have experienced the illness for six months or longer ("duration").[50]

The original study also including a determination of severity of symptoms ("severity"). "Severe cases were identified if at least one symptom in each of the required categories was rated as severe. Of 1,155 participating Gulf War veterans, 6% had severe CMI, and 39% had mild to moderate CMI; of the 2,520 nondeployed era veterans Of 1,155 participating Gulf War veterans, 6% had severe CMI, and 39% had mild to moderate CMI; of the 2,520 nondeployed era veterans, 0.7% had severe and 14% had mild to moderate CMI."[50]

Treatment

A 2013 report by the Institute of Medicine reviewed the peer-reviewed published medical literature for evidence regarding treatments for symptoms associated with chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) in 1990–91 Gulf War veterans, and in other chronic multisymptom conditions. For the studies the report reviewed that were specifically regarding CMI in 1990–91 Gulf War veterans (Gulf War illness), the report made the following conclusions:[29]

- Doxycycline: "Although the study of doxycycline was found to have high strength of evidence and was conducted in a group of 1991 Gulf War veterans who had CMI, it did not demonstrate efficacy; that is, doxycycline did not reduce or eliminate the symptoms of CMI in the study population."

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Exercise: "These studies evaluated the effects of exercise and CBT in combination and individually. The therapeutic benefit of exercise was unclear in those studies. Group CBT rather than exercise may confer the main therapeutic benefit with respect to physical symptoms."

The report concluded: "On the basis of the evidence reviewed, the committee cannot recommend any specific therapy as a set treatment for [Gulf War] veterans who have CMI. The committee believes that a 'one-size-fits-all' approach is not effective for managing [Gulf War] veterans who have CMI and that individualized health care management plans are necessary."[29]

By contrast, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) noted in a May 2018 publication that the primary focus of its Gulf War illness Research Program (GWIRP) "has been to fund research studies to identify treatment targets and test interventional approaches to alleviate symptoms. While most of these studies remain in progress, several have already shown varying levels of promise as GWI treatments."

According to the May 2018 DoD publication:[55]

Published Results on Treatments

The earliest federally funded multi-center clinical trials were VA- and DoD-funded trials that focused on antibiotic treatment (doxycycline) (Donta, 2004) and cognitive behavioral therapy with exercise (Donta, 2003). Neither intervention provided long-lasting improvement for a substantial number of Veterans.

Preliminary analysis from a placebo-controlled trial showed that 100 mg of Coenzyme Q10 (known as CoQ10 or Ubiquinone) significantly improved general self-reported health and physical functioning, including among 20 symptoms, each of which was present in at least half of the study participants, with the exception of sleep. These improvements included reducing commonly reported symptoms of fatigue, dysphoric mood, and pain (Golomb, 2014). These results are currently being expanded in a GWIRP-funded trial of a "mitochondrial cocktail" for GWI of CoQ10 plus a number of nutrients chosen to support cellular energy production and defend against oxidative stress. The treatment is also being investigated in a larger, VA- sponsored Phase III trial of Ubiquinol, the reduced form of CoQ10.

In a randomized, sham-controlled VA-funded trial of a nasal CPAP mask (Amin, 2011-b), symptomatic GW Veterans with sleep-disordered breathing receiving the CPAP therapy showed significant improvements in fatigue scores, cognitive function, sleep quality, and measures of physical and mental health (Amin, 2011a).

Preliminary data from a GWIRP-funded acupuncture treatment study showed that Veterans reported significant reductions in pain and both primary and secondary health complaints, with results being more positive in the bi-weekly versus weekly treatment group (Conboy, 2012). Current studies funded by the GWIRP and the VA are also investigating yoga as a treatment for GWI.

An amino acid supplement containing L-carnosine was found to reduce irritable bowel syndrome-associated diarrhea in a randomized, controlled GWIRP-funded trial in GW Veterans (Baraniuk, 2013). Veterans receiving L-carnosine showed a significant improvement in performance in a cognitive task, but no improvement in fatigue, pain, hyperalgesia, or activity levels.

Results from a 26 week GWIRP-funded trial comparing standard care to nasal irrigation with either saline or a xylitol solution revealed that both irrigation protocols reduced GWI respiratory (chronic rhinosinusitis) and fatigue symptoms (Hayer, 2015).

Administration of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist mifepristone to GW Veterans in a GWIRP-funded randomized trial resulted in an improvement in verbal learning, but no improvement in self-reported physical health or other self-reported measures of mental health (Golier, 2016).

Ongoing Intervention Studies

The GWIRP is currently funding many early-phase clinical trials aimed at GWI. Interventions include direct electrical nerve stimulation, repurposing FDA-approved pharmaceuticals, and dietary protocols and/or nutraceuticals. Both ongoing and closed GWIRP-supported clinical treatment trials and pilot studies can be found at http://cdmrp.army.mil/gwirp/resources/cinterventions.shtml.

A Clinical Consortium Award was offered [in FY2017] to support a group of institutions, coordinated through an Operations Center that will conceive, design, develop, and conduct collaborative Phase I and II clinical evaluations of promising therapeutic agents for the management or treatment of GWI. These mechanisms were designed to build on the achievements of the previously established consortia and to further promote collaboration and resource sharing.

The U.S Congress has made significant and continuing investment in DoD's Gulf War illness treatment research, with $129 million appropriated for the GWIRP between federal fiscal years (FY) 2006 and 2016.[56] The funding has risen from $5 million in FY2006, to $20 million each year from FY2013 through FY2017,[57] and to $21 million for FY2018.[58]

Prognosis

According to the May 2018 DoD publication cited above, "Research suggests that the GWI symptomology experienced by Veterans has not improved over the last 25 years, with few experiencing improvement or recovery ... . Many [Gulf War] Veterans will soon begin to experience the common co-morbidities associated with aging. The effect that aging will have on this unique and vulnerable population remains a matter of significant concern, and population-based research to obtain a better understanding of mortality, morbidity, and symptomology over time is needed."[55]

Prevalence

The 2008 and 2014 VA (RAC) reports and the 2010 IOM report found that the chronic multisymptom illness in Gulf War veterans—Gulf War illness—is more prevalent in Gulf War veterans than their non-deployed counterparts or veterans of previous conflicts.[9][11][47] While a 2009 study found the pattern of comorbidities similar for actively deployed and nondeployed Australian military personnel, the large body of U.S. research reviewed in the VA and IOM reports showed the opposite in U.S. troops.[59] The VA's 2014 RAC report found Gulf War illness in "an excess of 26–32 percent of Gulf War veterans compared to nondeployed era veterans" in pre-2008 studies, and "an overall multisymptom illness prevalence of 37 percent in Gulf War veterans and an excess prevalence of 25 percent" in a later, larger VA study.[11]

According to a May 2018 report by the U.S. Department of Defense, "GWI is estimated to have affected 175,000 to 250,000 of the nearly 700,000 troops deployed to the 1990–1991 GW theater of operations. Twenty-seven of the 28 Coalition members participating in the GW conflict have reported GWI in their troops. Epidemiologic studies indicate that rates of GWI vary in different subgroups of GW Veterans. GWI affects Veterans who served in the U.S. Army and Marines Corps at higher rates than those who served in the Navy and Air Force, and U.S. enlisted personnel are affected more than officers. Studies also indicate that GWI rates differ according to where Veterans were located during deployment, with the highest rates among troops who served in forward areas."[55]

Research

Epidemiologic studies have looked at many suspected causal factors for Gulf War illness as seen in veteran populations. Below is a summary of epidemiologic studies of veterans displaying multisymptom illness and their exposure to suspect conditions from the 2008 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs report.[60]

A fuller understanding of immune function in ill Gulf War veterans is needed, particularly in veteran subgroups with different clinical characteristics and exposure histories. It is also important to determine the extent to which identified immune perturbations may be associated with altered neurological and endocrine processes that are associated with immune regulation.[61] Very limited cancer data have been reported for U.S. Gulf War veterans in general, and no published research on cases occurring after 1999. Because of the extended latency periods associated with most cancers, it is important that cancer information is brought up to date and that cancer rates be assessed in Gulf War veterans on an ongoing basis. In addition, cancer rates should be evaluated in relation to identifiable exposure and location subgroups.[62]

| Epidemiologic studies of Gulf War veterans: association of deployment exposures with multisymptom illness[63] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected causative agent | Preliminary analysis (no controls for exposure) |

Adjusted analysis (controlled for effects of exposure) |

Clinical evaluations | |||

| GWV population in which association was ... |

GWV population in which association was ... | |||||

| assessed | statistically significant | assessed | statistically significant | Dose response effect identified? | ||

| Pyridostigmine bromide | 10 | 9 | 6 | 6 | ✓ | Associated with neurocognitive and HPA differences in GW vets |

| Pesticides | 10 | 10 | 6 | 5 | ✓ | Associated with neurocognitive and HPA differences in GW vets |

| Physiological stressors | 14 | 13 | 7 | 1 | ||

| Chemical weapons | 16 | 13 | 5 | 3 | Associated with neurocognitive and HPA differences in GW vets | |

| Oil well fires |

9 | 8 | 4 | 2 | ✓ | |

| Number of vaccines |

2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ✓ | |

| Anthrax vaccine |

5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Tent heater exhaust | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Sand / particulates | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Depleted uranium |

5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

Controversies

An early argument in the years following the Gulf War was that similar syndromes have been seen as an after effect of other conflicts — for example, "shell shock" after World War I, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the Vietnam War.[64] Cited as evidence for this argument was a review of the medical records of 15,000 American Civil War soldiers showing that "those who lost at least 5% of their company had a 51% increased risk of later development of cardiac, gastrointestinal, or nervous disease."[65]

Early Gulf War research also failed to accurately account for the prevalence, duration, and health impact of Gulf War illness. For example, a November 1996 article in the New England Journal of Medicine found no difference in death rates, hospitalization rates, or self-reported symptoms between Persian Gulf veterans and non-Persian Gulf veterans. This article was a compilation of dozens of individual studies involving tens of thousands of veterans. The study did find a statistically significant elevation in the number of traffic accidents suffered by Gulf War veterans.[66] An April 1998 article in Emerging Infectious Diseases similarly found no increased rate of hospitalization and better health on average for veterans of the Persian Gulf War in comparison to those who stayed home.[67]

In contrast to those early studies, in January 2006, a study led by Melvin Blanchard published in the Journal of Epidemiology, part of the "National Health Survey of Gulf War-Era Veterans and Their Families", found that veterans deployed in the Persian Gulf War had nearly twice the prevalence of chronic multisymptom illness, a cluster of symptoms similar to a set of conditions often at that time called Gulf War Syndrome.[68]

On November 17, 2008, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses (RAC), a Congressionally mandated federal advisory committee composed of VA-appointed clinicians, researchers, and representative Gulf War veterans,[69] issued a major report announcing scientific findings, in part, that "Gulf War illness is real", that GWI is a distinct physical condition, and that it is not psychological in nature. The 454 page report reviewed 1,840 published studies to form its conclusions identifying the high prevalence of Gulf War illness, suggesting likely causes rooted in toxic exposures while ruling out combat stress as a cause, and opining that treatments likely could be found. It recommended that Congress increase funding for treatment-focused Gulf War illness research to at least $60 million per year.[70][40]

In March 2013, a hearing was held before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives, to determine not whether Gulf War illness exists, but rather how it is identified, diagnosed and treated, and how the tools put in place to aid these efforts have been used.[71]

By 2016, the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) concluded there was sufficient evidence of a positive association between deployment to the 1990–1991 Gulf War and Gulf War illness.[72]

Jones controversy

Louis Jones Jr., the perpetrator of the 1995 murder of Tracie McBride, stated that the Gulf War syndrome caused him to commit the crime and he sought clemency, hoping to avoid the death penalty given to him by a federal court.[73] Jones was executed in 2003.[74]

Related legislation

On March 14, 2014, Representative Mike Coffman introduced the Gulf War Health Research Reform Act of 2014 (H.R. 4261; 113th Congress) into the United States House of Representatives, where it passed the House by unanimous consent but then died in Congress when the Senate failed to take action on it.[75] The bill would have altered the relationship between the Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses (RAC) and the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) under which the RAC is constituted. The bill would have made the RAC an independent organization within the VA, require that a majority of the RAC's members be appointed by Congress instead of the VA, and authorized the RAC to release its reports without needing prior approval from the VA Secretary.[76][77] The RAC is responsible for investigating Gulf War illness, a chronic multisymptom disorder affecting returning military veterans of the 1990–91 Gulf War.[4]

In the year prior to the consideration of this bill, the VA and the RAC were at odds with one another.[77] The VA replaced all but one of the members of the RAC, removed some of their supervisory tasks, tried to influence the board to decide that stress, rather than biology was the cause of Gulf War illness, and told the RAC that it could not publish reports without permission.[77] The RAC was created after Congress decided that the VA's research into the issue was flawed, and focused on psychological causes, while mostly ignoring biological ones.[77]

The RAC was first authorized under the Veterans Programs Enhancement Act of 1998 (Section 104 of Public Law 105-368, enacted November 11, 1998, and now codified as 38 U.S.C. § 527 note).[21][22] While the law directing its creation mandated that it be established not later than January 1, 1999,[22] the RAC's first charter was not issued until January 23, 2002, by VA Secretary Anthony Principi.[78] The RAC convened for its first meetings on April 11–12, 2002.[14]

See also

- Organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy

- Environmental issues with war

- Michael Donnelly, an activist for sufferers of Gulf War illness

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

References

- "Gulf War and Health: Treatment for Chronic Multisymptom Illness". Health and Medicine Division. nationalacademies.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017.

- "U.S. Chemical and Biological Warefare-related Dual Use Exports to Iraq and their Possible Impact on the Health Consequences of the Persian Gulf War" (PDF). United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. May 25, 1994.

A Report of Chairman Donald W. Riegle, Jr., and Ranking Member Alfonse M. D'Amato of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs with respect to Export Administration – United States Senate

- "Gulf War Veterans' Medically Unexplained Illnesses". Veterans Health. Public Health. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

- "Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses: Illnesses Associated with Gulf War Service". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. nd. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Iversen A, Chalder T, Wessely S (October 2007). "Gulf War Illness: lessons from medically unexplained symptoms". Clin Psychol Rev. 27 (7): 842–854. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.006. PMID 17707114.

- Gronseth GS (May 2005). "Gulf war syndrome: a toxic exposure? A systematic review". Neurol Clin. 23 (2): 523–540. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2004.12.011. PMID 15757795.

- "Gulf War Syndrome". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 14 July 2004.

- Stencel, C (9 April 2010). "Gulf War service linked to post-traumatic stress disorder, multisymptom illness, other health problems, but causes are unclear". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses (1 November 2008). "Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Scientific Findings and Recommendations" (PDF). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Li, B.; Mahan, C. M.; Kang, H. K.; Eisen, S. A.; Engel, C. C. (2011). "Longitudinal Health Study of US 1991 Gulf War Veterans: Changes in health status at 10-year follow-up". American Journal of Epidemiology. 174 (7): 761–768. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr154. PMID 21795757.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Research Update and Recommendations, 2009–2013: Updated Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. May 2014. pp. 3, 9–10, 20.

- White, Roberta F.; Steele, Lea; O'Callaghan, James P.; Sullivan, Kimberly; Binns, James H.; Golomb, Beatrice A.; Bloom, Floyd E.; Bunker, James A.; Crawford, Fiona (1 January 2016). "Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: Effects of toxicant exposures during deployment". Cortex. What's your poison? Neurobehavioural consequences of exposure to industrial, agricultural and environmental chemicals. 74: 449–475. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.08.022. ISSN 0010-9452. PMC 4724528. PMID 26493934.

- Kennedy, Kelly (23 January 2013). "Report: New vets show Gulf War illness symptoms". Army Times. USA Today. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Pre 2014 Archived Meetings and Minutes, Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses". U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Doyle, P.; MacOnochie, N.; Ryan, M. (2006). "Reproductive health of Gulf War veterans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 361 (1468): 571–584. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1817. PMC 1569619. PMID 16687262.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2008. p. 50 (p. 60 in PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- "The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service" (PDF). va.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2016.

- Barth, Shannon K.; Dursa, Erin K.; Bossarte, Robert M.; Schneiderman, Aaron I. (October 2017). "Trends in brain cancer mortality among U.S. Gulf War veterans: 21 year follow-up". Cancer Epidemiology. 50 (Part A): 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012. ISSN 1877-783X. PMC 5824993. PMID 28780478.

- "Gulf War exposures announcement". publichealth.va.gov. Archived from the original on 18 December 2009.

- Gulf War Illnesses (Report). U.S. Senate Veterans Affairs Committee. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013., Testimony to the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee by Meryl Nass, MD on September 25, 2007

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. "Authorizing Legislation" (PDF). Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- U.S. Government Printing Office. "Veterans Programs Enhancement Act of 1998, Public Law 105–368 Section 104, 112 STAT. 3315" (PDF). Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "Scientific Progress in Understanding Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses: Report and Recommendations" (PDF). United States Department of Veterans Affairs. September 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Depleted Uranium". GlobalSecurity.org. nd. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Jiang, G. C.; Aschner, M. (2006). "Neurotoxicity of depleted uranium: Reasons for increased concern". Biological Trace Element Research. 110 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1385/BTER:110:1:1. PMID 16679544.

- Faa, A.; et al. (2018). "Depleted uranium and human health". Current Medicinal Chemistry (Review Article). 25 (1): 49–64. doi:10.2174/0929867324666170426102343. PMID 28462701 – via researchgate.net.

- "Depleted Uranium". Public Health. publichealth.va.gov.

- "Pyridostigmine bromide use in the First Gulf War". Frontline. PBS. 1 December 1996. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Committee on Gulf War and Health: Treatment for Chronic Multisymptom Illness; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine (2013). Gulf War and Health: Treatment for Chronic Multisymptom Illness. National Academies Press. p. 13.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Organophosphate-Induced Delayed Neuropathy - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Qiang, D; Xie, X; Gao, Z (2017). "New insights into the organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 381: 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2017.08.451.

- Office of the Special Assistant to the Undersecretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) for Gulf War Illnesses Medical Readiness and Military Deployments (17 April 2003). Environmental Exposure Report: Pesticides Final Report. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Defense.

- Krengel, M.; Sullivan, K. (1 August 2008). Neuropsychological Functioning in Gulf War Veterans Exposed to Pesticides and Pyridostigmine Bromide. Fort Detrick, MD: U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2012. W81XWH-04-1-0118

- Friis, Robert H.; Thomas A. Sellers (2004). Epidemiology for Public Health Practice. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-3170-0.

- Spektor, Dalia M.; Rettig, Richard A.; Hilborne, Lee H.; Golomb, Beatrice Alexandra; Marshall, Grant N.; Davis, L. M.; Sherbourne, Cathy Donald; Harley, Naomi H.; Augerson, William S.; Cecchine, Gary (1998). A Review of the Scientific Literature as it Pertains to Gulf War Illnesses. United States Dept. of Defense. RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-2680-4.

- "Campaigners hail 'nerve gas link' to Gulf War Syndrome". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, UK. 13 November 2004. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- Riegle, D. W. (9 February 1994), U.S. Chemical and Biological Warfare-Related Dual Use Exports to Iraq and their Possible Impact on the Health Consequences of the Gulf War, Wikisource, archived from the original on 6 July 2012, retrieved 9 May 2012

- Persian Gulf War Illnesses Task Force (9 April 1997). "Khamisiyah: A Historical Perspective on Related Intelligence". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Golomb BA (March 2008). "Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and Gulf War illnesses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (11): 4295–300. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.4295G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711986105. PMC 2393741. PMID 18332428.

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2008). Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- Cordesman, AH (1999). Iraq and the War of Sanctions: Conventional Threats and Weapons of Mass Destruction. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96528-0.

- Chan, KC (11 October 2000). "GAO-01-92T Anthrax Vaccine: Preliminary Results of GAO's Survey of Guard/Reserve Pilots and Aircrew Members" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Burdeau, C. (16 May 2001). "Expert: Anthrax vaccine not proven". The Clarion-Ledger. Archived from the original on 7 November 2001. ("original source". The Clarion-Ledger. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012.)

- McNeil MM, Chiang IS, Wheeling JT, Zhang Y (March 2007). "Short-term reactogenicity and gender effect of anthrax vaccine: analysis of a 1967–1972 study and review of the 1955–2005 medical literature". Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 16 (3): 259–74. doi:10.1002/pds.1359. PMID 17245803.

- Petrik, Michael; et al. (February 2007). "Aluminum adjuvant linked to gulf war illness induces motor neuron death in mice". Neuromolecular Medicine. 9 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1385/NMM:9:1:83. PMID 17114826.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2008. p. 123 (p.133 in PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Gulf War and Health. 8. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 2010. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-309-14921-1.

Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War, Update 2009; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences

- Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Gulf War and Health. 8. National Academies Press. p. 260.

- "VA Benefits for Gulf War Syndrome". fight4vets. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 2014. pp. 90–99. ISBN 978-0-309-29877-3. OCLC 880456748.

- "Information for Veterans" (PDF). War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Gulf War Illness.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development (19 October 2017). "Researchers find evidence of DNA damage in Vets with Gulf War illness".

- "Gulf War Veterans' Medically Unexplained Illnesses". Veterans Health Administration. publichealth.va.gov. Public Health. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014.

- "A Guide to Gulf War Veterans' Health" (PDF). 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2006.

- "The Gulf War Illness Landscape" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. May 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program

- "Gulf War Illness Research Program, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs". cdmrp.army.mil. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ""Gulf War Illness Research Program", Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs" (PDF). cdmrp.army.mil. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Funding Opportunities-FY18 GWIRP, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (CDMRP), US DoD". cdmrp.army.mil. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Kelsall, H.L.; McKenzie, D.P.; Sim, M.R.; Leder, K.; Forbes, A.B.; Dwyer, T. (2009). "Physical, psychological, and functional comorbidities of multisymptom illness in Australian male veterans of the 1991 Gulf War". Am J Epidemiol. 170 (8): 1048–56. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp238. PMID 19762370.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2008. p. 220 (p. 230 in PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2008. p. 262 (p. 272 in PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2008. p. 45 (p. 55 in PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, Scientific Findings and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2008. p. 222 (p. 232 in PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2014.

- Hyams, Kenneth C. (1 September 1996). "War Syndromes and Their Evaluation: From the U.S. Civil War to the Persian Gulf War". Annals of Internal Medicine. 125 (5): 398–405. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00007. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 8702091.

- Pizarro, Judith; Silver, Roxane Cohen; Prause, JoAnn (1 February 2006). "Physical and Mental Health Costs of Traumatic War Experiences Among Civil War Veterans". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.193. ISSN 0003-990X. PMC 1586122. PMID 16461863.

- Gray, Gregory C.; Coate, Bruce D.; Anderson, Christy M.; Kang, Han K.; Berg, S. William; Wignall, F. Stephen; Knoke, James D.; Barrett-Connor, Elizabeth (14 November 1996). "The Postwar Hospitalization Experience of U.S. Veterans of the Persian Gulf War". New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (20): 1505–1513. doi:10.1056/nejm199611143352007. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 8890103.

- Knoke, J.D.; Gray, G.C. (1998). "Hospitalizations for unexplained illnesses among U.S. veterans of the Persian Gulf War". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (2): 211–219. doi:10.3201/eid0402.980208. PMC 2640148. PMID 9621191.

- Purdy, M.C. (20 January 2006). "Study finds multisymptom condition is more prevalent among Persian Gulf vets". Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses home page". va.gov. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Silverleib, A. (9 December 2008). "Gulf War illness is real, new federal report says". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Gulf War: What Kind of Care Are Veterans Receiving 20 Years Later?". Committee on Veterans' Affairs. U.S. House of Representatives.

Hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Veterans' Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, First Session, Wednesday, March 13, 2013.

- Cory-Slechta, Deborah; Wedge, Roberta, eds. (2016). Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Gulf War and Health. 10. Fulco, Carolyn; Liverman, Catharyn T.; Sox, Harold C.; Mitchell, Abigail E.; Sivitz, Laura; Black, Robert E. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-309-07178-9. OCLC 45180227.

Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

- Miller, Mark (12 March 2003). "Should Louis Jones die?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Collins, Dan (19 February 2003). "Gulf War vet executed". CBS News. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Coffman, Mike (2 June 2014). "Actions – H.R.4261 – 113th Congress (2013–2014): Gulf War Health Research Reform Act of 2014". congress.gov. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Coffman, Mike (14 March 2014). "Bipartisan Bill on Gulf War Health Research". House Office of Mike Coffman. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Kennedy, Kelly (14 March 2014). "Congress seeks independence for Gulf War illness board". USA Today. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. "Archived Committee Charters, Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses". Retrieved August 15, 2019.

External links

| Classification |

|---|