Guillaume Faye

Guillaume Faye (French: [ɡijom faj]; 7 November 1949 – 6 March 2019) was a French journalist, writer, and advocate of Identitarianism as part of the French New Right. Continuing the tradition of Giorgio Locchi,[1] Faye was instrumental in positioning Islam as the nemesis of the Western world. His various articles and books suggested an incoherence of ideology in postwar Europe and a quest for a nemesis necessary for the templative fascism to win support. Earlier in his career, anti-Semitism permeated his work; later on, criticism of Islam took that role.

Guillaume Faye | |

|---|---|

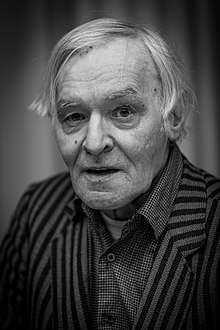

Guillaume Faye in 2015 | |

| Born | 7 November 1949 |

| Died | 6 March 2019 (aged 69) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

Biography

Early life and education

Guillaume Faye was born on 7 November 1949 in Angoulême from a bourgeois family close to the Bonapartist right.[1] He attended the Paris Institute of Political Studies, where he ran the student's associations Cercle Pareto and Association GRECE between 1971 and 1973.[2][1]

GRECE

On the advice of Dominique Venner, Faye joined GRECE in 1970, an ethno-nationalist think tank led by Nouvelle Droite thinker Alain de Benoist.[3] He soon became one of the major theorists and the Secretary for Studies and Research of the movement. Faye wrote at that time for many New Right journals such as Éléments, Nouvelle École, Orientations, and Études et Recherches.[1] From 1978, he became a promoter of the strategy of "metapolitics" embodied by GRECE, although he eventually failed his project of entryism within the mainstream right-wing Figaro Magazine.[4]

Media career

After intellectual and financial disagreements with de Benoist, Faye was marginalized in GRECE. He is said to have been ousted from the think tank in late 1986, although his departure was not officially announced until August 1987, via a letter wrote by Pierre Vial to Le Monde.[5]

Faye then distanced himself from political activism and was actively involved with the media industry. Between 1991 and 1993, he worked as an entertainer under the name of 'Skyman' at the radio station Skyrock.[4] He was also a journalist at L'Écho des Savanes and VSD, and he appeared in Télématin episodes on the France 2 public TV channel.[6] Faye taught the sociology of sexuality at the University of Besançon,[7] and he has also claimed to have acted in pornographic films.[4]

Return to political activism

Faye went back to political activism in 1998 with the writing of Archeofuturism, followed in 2000 by The Colonization of Europe.[8] The latter, criticized as "strongly racist" by de Benoist, earned him a criminal conviction for incitement to racial hatred.[9] Faye organized conferences with GRECE sympathizers, Monarchists, Traditional Catholics and neo-Pagans. At the request of de Benoist, however, he was excluded from GRECE in May 2000.[8]

Faye then became close to Terre et Peuple, a neo-Pagan movement founded in 1995 by former GRECE members Pierre Vial, Jean Mabire and Jean Haudry, but he was also expelled in 2007 after the publication of his book The New Jewish Question ('La Nouvelle Question Juive'),[8] considered within some revolutionary-nationalist and Catholic traditionalists circles to be overly "Zionist".[10] In 1999 and 2002, he was invited as a speaker by the Club de l'Horloge, a national-liberal think tank led by Henry de Lesquen.[11]

After a long battle with cancer, Faye died on 6 March 2019.[12]

Ideas

GRECE period (1970–1987)

A key concept of Faye's thought is that paganism, which he views as a quasi-ideal object aligned on the cosmic order and allowing for a holistic and organic society, is a rooted and differentialist religion, and thus a solution to the dominant "mixophile" and universalist worldview.[4] Faye has also participated in the diffusion of an identity defined as biological and cultural.[13] He 1979, he argued that immigration, rather than immigrants, should be combated in order to preserve cultural and biological "identities" on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea.[14]

His first books, published in the beginning of the 1980s, were a rejection of the consumerist society and the standardization and Westernization of the world, one of Faye's intellectual constants. For him a multiracial society is by essence "multiracist", and he has called for the return of non-European immigrants to their 'civilizational area'.[13] In 1985, Faye stated that Zionist "opinion circles" in France had forced the French government to break ties with the Ba'athist regime of Saddam Hussein, and he has denounced "Zionist lobbies" in the US wishing to influence geopolitics in favour of Israel.[13] After his return to politics in the late 1990s, however, Faye reversed from his pro-Arab positions and became a supporter of Israel as a potential political ally against Arabs and Muslims.[15]

Later period (1998–2019)

After the late 1990s, in books he conceived as an appeal to the "ethnic awareness" of Europeans, Faye became an important ideologue of nativism, advocating a racialism that Stéphane François has described as "reminiscent of the 1900s to the 1930s".[15] The "ethnic foundations of a civilization", Faye wrote, "rest on its biological roots and those of its peoples."[10] He has also made references to the "loyalty to values and to bloodlines", promoted natalist and eugenic politics to resolve Europe's demographic issues, and adopted a racialist Darwinian concept of the "struggle of the fittest", regarding other civilizations as enemies to be eliminated.[15]

Faye believes the West to be threatened by its demographic decline and decadent social fabric, a supposed ethnoreligious clash between the North and the South, as well as global financial crisis and uncontrolled environmental pollution. To avoid the announced civilizational and ecological collapse, Faye has promoted an authoritarian regime led by a "born chief", a charismatic and providential man protecting the people's identity and ancestry, and taking the right decisions in emergency situations.[7] Faye also condemned what he has called "ethnomasochism", defined as the self-hating of one's own ethnic group.[13] In Why We Fight, originally published in 2001, Faye defined 'metapolitics' as the "social diffusion of ideas and cultural values for the sake of provoking profound, long-term, political transformation."[16]

"Archeofuturism", a concept coined by Faye in 1998, refers to the reconciliation of technoscience with "archaic values".[17] He argues that the term "archaic" should be understood in its original Ancient Greek meaning as the 'foundation' or the 'beginning', not as an attachment to the past.[8] According to Faye, anti-moderns and counter-revolutionaries are actually mirror-constructs of modernity, sharing the same biased linear conception of time. Defining his theories as "non-modern", Faye was influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of eternal return and Michel Maffesoli's postmodern sociological works.[8] Political scientist Stéphane François has described archeofuturism as a combination of "postmodern philosophy, some elements of Western counterculture, and racism."[18]

Influence

In the 1980s, his work was translated into English, Italian, German, or Spanish, and Faye spoke at numerous conferences organized by European New Right groups. Although he had abandoned all political activities from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, his first books and articles continued to be discussed among American activists of the movement that was later called the "Alt Right".[7] Following his comeback, he renewed his links with GRECE and nationalist-revolutionary militants between 1998 and 2006, and became an important figure of "national-westernism", finding himself alongside European far-right militants the likes of Gabriele Adinolfi, Pierre Krebs, Ernesto Milá, Pierre Vial or Galina Lozko to defend the "future of the white world", as one conference organized in Moscow in June 2006 was titled.[19]

After 2006, Faye has taken part in conventions organized by the American Renaissance association led by Jared Taylor, and his ideas have been discussed by the American Alt Right website Counter-Currents.[10] His works from the second intellectual period have been translated in English by Arktos Media,[10] described as the "uncontested global leader in the publication of English-language Nouvelle Droite literature."[20] The writings of Faye and Alain de Benoist, especially their metapolitical stance, have also influenced American far-right activist Richard B. Spencer,[21] Swedish Identitarian Daniel Friberg, and the Identitarian movement at large.[22] As for de Benoist, Faye's writings were discussed in the American New Left journal Telos, founded by philosopher Paul Piccone.[23] According to Stéphane François, Faye "is responsible for the doctrinal renewal of French nativism and, more widely, for the development of the European-American radical Right".[18]

Works

- Le Système à tuer les peuples, Copernic 1981.

- Contre l'économisme, Le Labyrinthe, 1983.

- Sexe et Idéologie, Le Labyrinthe, 1983.

- La Nouvelle société de consommation, Le Labyrinthe, 1984.

- L'Occident comme déclin, Le Labyrinthe, 1984.

- Avant-guerre, Carrère, 1985.

- Nouveaux discours à la Nation Européenne, Albatros, 1985.

- Europe et modernité, Eurograf, 1985.

- Petit lexique du partisan européen (collaborator), Eurograf, 1985.

- Les Nouveaux enjeux idéologiques, Le Labyrinthe, 1985.

- La Soft-idéologie (collaborator as Pierre Barbès), Robert Laffont, 1987.

- Le Guide de l'engueulade, Presses de la Cité, 1992.

- Viol, pillage, esclavagisme, Christophe Colomb, cet incompris : essai historico-hystérique, Grancher, 1992.

- Le Manuel du séducteur pressé, Presses de la Cité, 1993.

- L'Archéofuturisme, L'Aencre, 1998. English translation: Archeofuturism, Arktos, 2010.

- La Colonisation de l’Europe: discours vrai sur l’immigration et l’Islam, L’Æncre, 2000. English translation: The Colonisation of Europe, Arktos, 2016.

- Les Extra-terrestres de A à Z, Dualpha, 2000.

- Pourquoi nous combattons: manifeste de la résistance européenne, L’Æncre, 2001. English translation: Why We Fight: Manifesto of the European Resistance, Arktos, 2011.

- Chirac contre les fachos, GFA, 2002.

- Avant-guerre, L’Aencre, 2002.

- Le coup dEtat mondial: Essai sur le Nouvel Impérialisme Américain., L’Æncre, 2004. English translation: A Global Coup, Arktos, 2017.

- La congergence des catastrophes., L’Æncre, 2004. English translation: Convergence of Catastrophes, Arktos, 2012.

- La Nouvelle Question juive, Le Lorre, 2007.

- Sexe et Dévoiement, Les éditions du Lore, 2011. English translation: Sex and Deviance, Arktos, 2014.

- L'Archéofuturisme V2.0 : nouvelles cataclysmiques, Le Lorre, 2012. English translation: Archaeofuturism 2.0, Arktos, 2016.

- Mon programme: Un programme révolutionnaire ne vise pas à changer les règles du jeu mais à changer de jeu , Les Éditions du Lore, 2012.

- Comprendre l'islam, Tatamis, 2015. English translation: Understanding Islam, Arktos, 2016.

- Guerre civile raciale, Éditions Conversano, 2019. English translation: Ethnic Apocalypse: The Coming European Civil War, Arktos, 2019 (foreword by Jared Taylor)

References

- François 2019, p. 92.

- Lamy 2016, p. 274.

- Lamy 2016, pp. 274–275.

- François 2019, p. 93.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 139.

- Francois, Stephane (2020). L'occultisme nazi (in French). CNRS Édition. pp. n. 488. ISBN 978-2-271-13172-0.

- François 2019, p. 97.

- François 2019, p. 94.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 141.

- François 2019, p. 98.

- Lamy 2016, p. 267 n. 5.

- Scianca, Adriano (7 March 2019). "È morto Guillaume Faye, l'uomo che ha cambiato il pensiero non conforme europeo". Il Primato Nazionale (in Italian). Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- François 2019, p. 95.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 124.

- François 2019, p. 96.

- Teitelbaum 2019, "Daniel Friberg and Metapolitics in Action", p. 260; citing Faye, Guillaume (2011). Why We Fight: Manifesto of the European Resistance. Arktos. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-907166-19-8.

- François 2008, p. 187.

- François 2019, p. 91.

- François 2019, pp. 97–98.

- Teitelbaum 2017, p. 51.

- Bar-On, Tamir (2019). "Richard B. Spencer and the Alt Right". In Sedgwick, Mark (ed.). Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Behind the New Threat to Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-19-087760-6.

Richard B. Spencer and the Alt Right", p. 226: "Spencer believes that white racial consciousness and political solidarity can be attained without violence, continuing the French New Right’s “right-wing Gramscianism,” which was promoted by de Benoist and Guillaume Faye.

- Teitelbaum 2017, p. 45.

- François 2019, p. 99.

- Bibliography

- Camus, Jean-Yves; Lebourg, Nicolas (2017). Far-Right Politics in Europe. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674971530.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- François, Stéphane (2008). Les néo-paganismes et la Nouvelle droite, 1980-2006: pour une autre approche (in French). Archè. ISBN 978-88-7252-287-5.

- François, Stéphane (2019). "Guillaume Faye and Archeofuturism". In Sedgwick, Mark (ed.). Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Behind the New Threat to Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–101. ISBN 978-0-19-087760-6.

- Lamy, Philippe (2016). Le Club de l'Horloge (1974-2002) : évolution et mutation d'un laboratoire idéologique (PhD thesis) (in French). University of Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis.

- Teitelbaum, Benjamin R. (2017). Lions of the North: Sounds of the New Nordic Radical Nationalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-021259-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Avant-Guerre: Chronique d’un cataclysme annoncé (Pre-War: Account of an Impending Cataclysm).

- Le coup dEtat mondial: Essai sur le Nouvel Impérialisme Américain.