Commiphora wightii

Commiphora wightii, with common names Indian bdellium-tree,[3] gugal,[4] guggul,[3] gugul,[3] or Mukul myrrh tree, is a flowering plant in the family Burseraceae, which produces a fragrant resin called gugal, guggul or gugul, that is used in incense and vedic medicine (or ayurveda). The guggul plant may be found from northern Africa to central Asia, but is most common in northern India. It prefers arid and semi-arid climates and is tolerant of poor soil.

| Commiphora wightii | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Burseraceae |

| Genus: | Commiphora |

| Species: | C. wightii |

| Binomial name | |

| Commiphora wightii (Arn.) Bhandari | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Description

Commiphora wightii grows as a shrub or small tree, reaching a maximum height of 4 m (13 ft), with thin papery bark.[4] The branches are thorny. The leaves are simple or trifoliate, the leaflets ovate, 1–5 cm (0.39–1.97 in) long, 0.5–2.5 cm (0.20–0.98 in) broad, and irregularly toothed. It is gynodioecious, with some plants bearing bisexual and male flowers, and others with female flowers. The individual flowers are red to pink, with four small petals. The small round fruit are red when ripe.

Cultivation and uses

Commiphora wightii is sought for its gummy resin, which is harvested from the plant's bark through the process of tapping. In India and Pakistan, guggul is cultivated commercially. The resin of C. wightii, known as gum guggulu, has a fragrance similar to that of myrrh and is commonly used in incense and perfumes. It is the same product that was known in Hebrew, ancient Greek and Latin sources as bdellium.

Guggul is used in Ayurveda remedies and it is mentioned in Ayurvedic texts dating back to 600 BC. [5] It is often sold as a herbal supplement.

The gum can be purchased in a loosely packed form called dhoop, an incense from India, which is burned over hot coals. This produces a fragrant, dense smoke. [6] It is also sold in the form of incense sticks and dhoop cones which can be burned directly.

Chemical composition

Over a hundred metabolites of various chemical compositions were reported from the leaves, stem, latex, root and fruit samples. High concentrations of quinic acid and myo-inositol were found in fruits and leaves.[7]

Traditional medicinal use

Commiphora wightii has been a key component in ancient Indian Ayurvedic system of medicine.

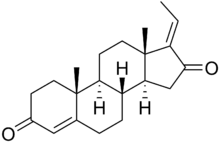

The extract of gum guggul, called gugulipid, guggulipid, or guglipid, has been used in Unani and Ayurvedic medicine, for nearly 3,000 years in India.[8][9] One chemical ingredient in the extract is the steroid guggulsterone,[10] which acts as an antagonist of the farnesoid X receptor, once believed to result in decreased cholesterol synthesis in the liver. However, several studies have been published that indicate no overall reduction in total cholesterol occurs using various dosages of guggulsterone and levels of low-density lipoprotein ("bad cholesterol") increased in many people.[11][12]

Endangerment and rescue

Because of its use in traditional medicine, C. wightii has been overharvested, and has become so scarce in its two habitats in India—Gujarat and Rajasthan—that the World Conservation Union (IUCN) has enlisted it in its IUCN Red List of threatened species.[1] Several efforts are in place to address this situation. India's National Medicinal Plants Board launched a project in Kutch District to cultivate 500 to 800 hectares (1,200 to 2,000 acres) of guggal,[13] while a grass-roots conservation movement, led by IUCN associate Vineet Soni, has been started to educate guggal growers and harvesters in safe, sustainable harvesting methods.[14][15]

References

- Ved, D.; Saha, D.; Ravikumar, K.; Haridasan, K. (2015). "Commiphora wightii-Guggul". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T31231A50131117. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T31231A50131117.en.

- "Tropicos.org". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Commiphora wightii". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Sultanul Abedin & S.I. Ali. "Commiphora wightii". Flora of Pakistan. 26.

- "Guggul: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Dosage, and Warning". Web MD.

- "Guggul (Indian Bedellium)".

- Bhatia, Anil; Bharti, Santosh K.; Tripathi, Tusha; Mishra, Anuradha; Sidhu, Om P.; Roy, Raja; Nautiyal, Chandra Shekhar (1 February 2015). "Metabolic profiling of Commiphora wightii (guggul) reveals a potential source for pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals". Phytochemistry. 110: 29–36. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.12.016. PMID 25561401.

- Indian herb can reduce cholesterol Archived 2008-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, BBC NEWS, 2 May 2002

- Mohan, Mohind C.; Abhimannue, Anu P.; Kumar, B.Prakash (January 2019). "Modulation of proinflammatory cytokines and enzymes by polyherbal formulation Guggulutiktaka ghritam". Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2018.05.007. PMID 30638916.

- Murray (2012). Joseph E. Pizzorno Jr.; Michael T. (eds.). Textbook of natural medicine (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 691. ISBN 9781437723335.

- Szapary, PO; Wolfe, ML; Bloedon, LT; Cucchiara, AJ; Dermarderosian, AH; Cirigliano, MD; Rader, DJ (2003). "Guggulipid Ineffective for Lowering Cholesterol". JAMA. 290 (6): 765–772. doi:10.1001/jama.290.6.765. PMID 12915429.

- Sahni, S; Hepfinger, CA; Sauer, KA (2005). "Guggulipid Use in Hyperlipidemia". Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 62 (16): 1690–1692. doi:10.2146/ajhp040580. PMID 16085931.

- Maheshwari, D V (8 January 2008). "Kutch to house Centre's Rs 8-cr Guggal conservation project". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- Paliwal, Ankur (31 July 2010). "Guggal faces sticky end". Down to Earth: Science and Environment Online. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Education and Awareness in the 'Save Guggul Movement'". IUCN News. 31 July 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Commiphora wightii. |

- What's Gugul Good For?, David Jerklie, Time Magazine, Aug. 25, 2003

- Flora of Pakistan: Commiphora wightii

- Medicinal Plants of Conservation Concern: Commiphora wightii

- Caldecott, Todd (2006). Ayurveda: The Divine Science of Life. Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 978-0-7234-3410-8. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-01-15. Contains a detailed monograph on Commiphora mukul (Guggulu) as well as a discussion of purported health benefits and usage in clinical practice.

- Dalby, Andrew (2003). Food in the ancient world from A to Z. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23259-3., pp. 226–227