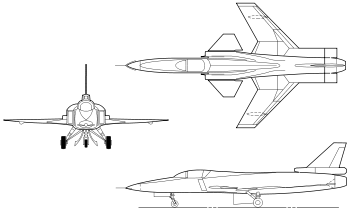

Grumman X-29

The Grumman X-29 was an American experimental aircraft that tested a forward-swept wing, canard control surfaces, and other novel aircraft technologies. The X-29 was developed by Grumman, and the two built were flown by NASA and the United States Air Force. The aerodynamic instability of the X-29's airframe required the use of computerized fly-by-wire control. Composite materials were used to control the aeroelastic divergent twisting experienced by forward-swept wings, and to reduce weight. The aircraft first flew in 1984, and two X-29s were flight tested through 1991.

| X-29 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Grumman X-29 in flight | |

| Role | Experimental aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Grumman |

| First flight | 14 December 1984 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | United States Air Force NASA |

| Number built | 2 |

Design and development

Two X-29As were built by Grumman from two existing Northrop F-5A Freedom Fighter airframes (63-8372 became 82-0003 and 65-10573 became 82-0049)[1] after the proposal had been chosen over a competing one involving a General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon. The X-29 design made use of the forward fuselage and nose landing gear from the F-5As with the control surface actuators and main landing gear from the F-16. The technological advancement that made the X-29 a plausible design was the use of carbon-fiber composites. The wings of the X-29, made partially of graphite epoxy, were swept forward at more than 33 degrees; forward-swept wings were first trialed 40 years earlier on the experimental Junkers Ju 287 and OKB-1 EF 131. The Grumman internal designation for the X-29 was "Grumman Model 712" or "G-712".[2]

Three-surface design and inherent instability

The X-29 is described as a three surface aircraft, with canards, forward-swept wings, and aft strake control surfaces,[3] using three-surface longitudinal control.[4] The canards and wings result in reduced trim drag and reduced wave drag, while using the strakes for trim in situations where the center of gravity is off provides less trim drag than relying on the canard to compensate.[3]

The configuration, combined with a center of gravity well aft of the aerodynamic center, made the craft inherently unstable. Stability was provided by the computerized flight control system making 40 corrections per second. The flight control system was made up of three redundant digital computers backed up by three redundant analog computers; any of the three could fly it on its own, but the redundancy allowed them to check for errors. Each of the three would "vote" on their measurements, so that if any one was malfunctioning it could be detected. It was estimated that a total failure of the system was as unlikely as a mechanical failure in an airplane with a conventional arrangement.[4]

The high pitch instability of the airframe led to wide predictions of extreme maneuverability. This perception has held up in the years following the end of flight tests. Air Force tests did not support this expectation.[5] For the flight control system to keep the whole system stable, the ability to initiate a maneuver easily needed to be moderated. This was programmed into the flight control system to preserve the ability to stop the pitching rotation and keep the aircraft from departing out of control. As a result, the whole system as flown (with the flight control system in the loop as well) could not be characterized as having any special increased agility. It was concluded that the X-29 could have had increased agility if it had faster control surface actuators and/or larger control surfaces.[5]

Aeroelastic considerations

In a forward swept wing configuration, the aerodynamic lift produces a twisting force which rotates the wing leading edge upward. This results in a higher angle of attack, which increases lift, twisting the wing further. This aeroelastic divergence can quickly lead to structural failure. With conventional metallic construction, a torsionally very stiff wing would be required to resist twisting; stiffening the wing adds weight, which may make the design unfeasible.[6]

The X-29 design made use of the anisotropic elastic coupling between bending and twisting of the carbon fiber composite material to address this aeroelastic effect. Rather than using a very stiff wing, which would carry a weight penalty even with the relatively light-weight composite, the X-29 used a laminate which produced coupling between bending and torsion. As lift increases, bending loads force the wing tips to bend upward. Torsion loads attempt to twist the wing to higher angles of attack, but the coupling resists the loads, twisting the leading edge downward reducing wing angle of attack and lift. With lift reduced, the loads are reduced and divergence is avoided.[6]

Operational history

The first X-29 took its maiden flight on 14 December 1984 from Edwards AFB piloted by Grumman's Chief Test Pilot Chuck Sewell.[1] The X-29 was the third forward-swept wing jet-powered aircraft design to fly; the other two were the German Junkers Ju 287 (1944) and the HFB-320 Hansa Jet (1964).[7] On 13 December 1985, an X-29 became the first forward-swept wing aircraft to fly at supersonic speed in level flight.

The X-29 began a NASA test program four months after its first flight. The X-29 proved reliable, and by August 1986 was flying research missions of over three hours involving multiple flights. The first X-29 was not equipped with a spin recovery parachute, as flight tests were planned to avoid maneuvers that could result in departure from controlled flight, such as a spin. The second X-29 was given such a parachute and was involved in high angle-of-attack testing. X-29 number two was maneuverable up to an angle of attack of about 25 degrees with a maximum angle of 67° reached in a momentary pitch-up maneuver.[8][9]

The two X-29 aircraft flew a total of 242 times from 1984 to 1991.[2][10] The NASA Dryden Flight Research Center reported that the X-29 demonstrated a number of new technologies and techniques, and new uses of existing technologies, including the use of "aeroelastic tailoring to control structural divergence", aircraft control and handling during extreme instability, three-surface longitudinal control, a "double-hinged trailing-edge flaperon at supersonic speeds", effective high angle of attack control, vortex control, and demonstration of military utility.[4]

Aircraft on display

The first X-29, 82-003, is now on display in the Research and Development Gallery at the National Museum of the United States Air Force on Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio.[11] The other craft is on display at the Armstrong Flight Research Center on Edwards Air Force Base. A full-scale model was on display from 1989 to 2011 at the National Air and Space Museum's National Mall building in Washington, DC.[12]

Specifications (X-29)

Data from Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1988-89[13]NASA X-Planes,[14] Donald,[2] Winchester[10]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Capacity: 4,000 lb (1,814 kg) payload

- Length: 53 ft 11.25 in (16.4402 m) including nose probe

- 48 ft 1 in (15 m) fuselage only

- Wingspan: 27 ft 2.5 in (8.293 m)

- Height: 14 ft 3.5 in (4.356 m)

- Wing area: 188.84 sq ft (17.544 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 3.9

- Airfoil: root: Grumman K MOD 2 (6.2%) ; tip: Grumman K MOD 2 (4.9%)[15]

- Empty weight: 13,800 lb (6,260 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 17,800 lb (8,074 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 3,978 lb (1,804 kg) in two fuselage bladder tanks and two strake integral tanks

- Powerplant: 1 × General Electric F404-GE-400 afterburning turbofan engine, 16,000 lbf (71 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 956 kn (1,100 mph, 1,771 km/h) at 33,000 ft (10,058 m)

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.8

- Range: 350 nmi (400 mi, 650 km)

- Service ceiling: 55,000 ft (17,000 m)

Avionics

- Litton LR-80 AHRS

- Magnavox AN/ARC-164 UHF

- Teledyne RT-1063B/APX-101V IFF/SIF

- Honeywell triple redundant fly-by-wire FCS

See also

- Junkers Ju 287

- Hansa Jet

- OKB-1 EF 131

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- Gehrs-Pahl, Andreas, ed. (1995). "The X-Planes: From X-1 to X-34". AIS.org. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Donald 1997, p. 483.

- Roskam 1985, pp. 85–87.

- "Fact Sheet: X-29 Advanced Technology Demonstrator Aircraft". NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Butts & Hoover 1989.

- Pamadi 2004.

- Green 1970, pp. 493–496.

- Webster & Purifoy 1991.

- Winchester 2005, p. 261.

- Winchester 2005, p. 262.

- "Grumman X-29A". National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. 28 May 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- "Beyond the Limits". National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Taylor, John W.R., ed. (1988). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1988-89 (79th ed.). London: Jane's Information Group. pp. 399–400. ISBN 0-7106-0867-5.

- Jenkins, Landis & Miller 2003, p. 37.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Butts, S. L.; Hoover, A. D. (May 1989). "Flying Qualities Evaluation of the X-29A Research Aircraft". U.S. Air Force Flight Test Center. AFFTC-TR-89-08. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Donald, David, ed. (1997). "Grumman X-29A". The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-0592-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, William (1970). Warplanes of the Third Reich. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-05782-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkins, Dennis R.; Landis, Tony; Miller, Jay (June 2003). American X-Vehicles: An Inventory—X-1 to X-50 (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History No. 31. NASA. OCLC 68623213. SP-2003-4531.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pamadi, Bandu N. (2004). Performance, Stability, Dynamics, and Control of Airplanes (2nd ed.). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/4.862274. ISBN 978-1-56347-583-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Putnam, Terrill W. (January 1984). X-29 Flight-Research Program (PDF). AIAA 2nd Flight Test Conference. Las Vegas, Nevada. 16–18 November 1983. NASA. TM-86025.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roskam, Jan (1985). Airplane Design, Part II: Preliminary Configuration Design and Integration of the Propulsion System. Ottawa, Kansas: Roskam Aviation and Engineering Corporation. ISBN 978-1-88488-543-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thruelsen, Richard (1976). The Grumman Story. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-54260-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Treadwell, Terry (1990). Ironworks: Grumman's Fighting Aeroplanes. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85310-070-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warwick, Graham (16 June 1984). "Forward-sweep Technology". Flight International: 1563–1568.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webster, Frederick R.; Purifoy, Dana (July 1991). X-29 High Angle-of-Attack Flying Qualities. U.S. Air Force Flight Test Center. AFFTC-TR-91-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winchester, Jim (2005). "Grumman X-29". X-Planes and Prototypes. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-904687-40-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grumman X-29. |

- X-29 fact sheet at NASA.gov

- X-29 fact sheet by the National Museum of the United States Air Force

- X-29 photos, and X-29 videos at NASA.gov

- "X-29: Aircraft with Forward Swept Wings", part 1, part 2 at Military.com